Ukraine war: Is the tank doomed?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesImages of destroyed Russian tanks - the shattered hull, broken turret, gun barrel blackened and burnt, pointing uselessly at the sky - have been a defining image of the war in Ukraine. It has led some to ask whether modern anti-tank weapons have rendered tanks useless on the battlefield.

"This is a story that comes around every time a tank gets knocked out," says David Willey, curator and instructor at the Tank Museum at Bovington, Dorset, which boasts the world's largest collection of tanks. "Because the tank is such a symbol of power, when it's defeated people jump to the conclusion it's the end of the tank."

We are watching a Soviet-designed T-72 main battle tank rev its engine and clatter towards the refuelling point before rehearsing for a demonstration. This is basically the same tank model that rolled across the border into Ukraine in February and destroyed in their hundreds by small, agile bands of well-trained Ukrainian infantry wielding drones, Javelin and Next Generation Light Anti-tank Weapons (Nlaws).

"It's important not to draw the wrong lessons from what we have witnessed over the past several months," says retired US Army Lt Gen Ben Hodges, who until recently commanded US land forces in Europe.

"The Russian tanks in question were typically poorly employed, unsupported by dismounted infantry, and without the benefit of a strong non-commissioned officer (NCO) corps, such as one finds in the US Army or British Army. Therefore, they were all easy kills for the defending Ukrainian forces."

His views are echoed by retired British Army Brigadier Ben Barry, now senior fellow for land warfare at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

"The defeat of the Russian attack on Kyiv shows what happens when tanks are inexpertly deployed by a force that cannot do combined arms warfare (combining tanks with infantry, artillery and aircraft) and has weak logistics.

"A competent Nato battle group would push out infantry to stop tanks being ambushed."

The tank - one of the iconic symbols of modern warfare - has both its critics and defenders. In the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Armenia's tanks got decimated by Azerbaijan's Turkish-made drones. In Libya, these same drones, the TB2 Bayraktar, inflicted serious losses on the forces of General Haftar, while in Syria, government tanks also fell prey to the Turkish drones.

In the early phase of the Ukraine war, modern anti-tank guided missiles, supplied by Britain, the US and other nations, proved to be a game-changer in driving back the Russian armoured columns from north of the capital, Kyiv. Meanwhile, in the second phase, in the Donbas, massed Russian artillery has been the game-changer, using destructive firepower to slowly blast its way forward.

So far this year, Russia is estimated to have lost more than 700 tanks - some destroyed, some abandoned. These tanks are often pictured covered in reactive armour - which looks like a large rectangular box. It is designed to set off a small explosion as the missile hits, blunting its effect.

But Western-supplied drones and anti-tank missiles have got around this, mainly by hitting the tank from above on the turret, where the armour is thinnest.

"This war has been the day of the drone," says Brig Barry. "It tells us that you need drones for defence to keep enemy drones off your back. You need classic low-level air defence including lasers and electronic jamming."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSomething that may prolong the future of the tank is the Active Protection System (APS). It is a way to head off whatever is attacking your tank before it hits you.

"There are two types of APS, soft and hard kill evasion suites," explains Bovington's David Willey.

He pauses while the nearby T72 tank, a gift from the Polish Army, belches blue exhaust fumes and swivels its massive 125mm gun menacingly in our direction.

"Soft kill means electronic pulses that can disrupt the incoming missile. Hard kill means firing something kinetic at it, like a stream of bullets."

As is so often the case, the Israeli military have researched this area exhaustively, especially since 2006 when their tanks took a beating from Hezbollah's IED's and skilfully deployed anti-tank missiles in south Lebanon.

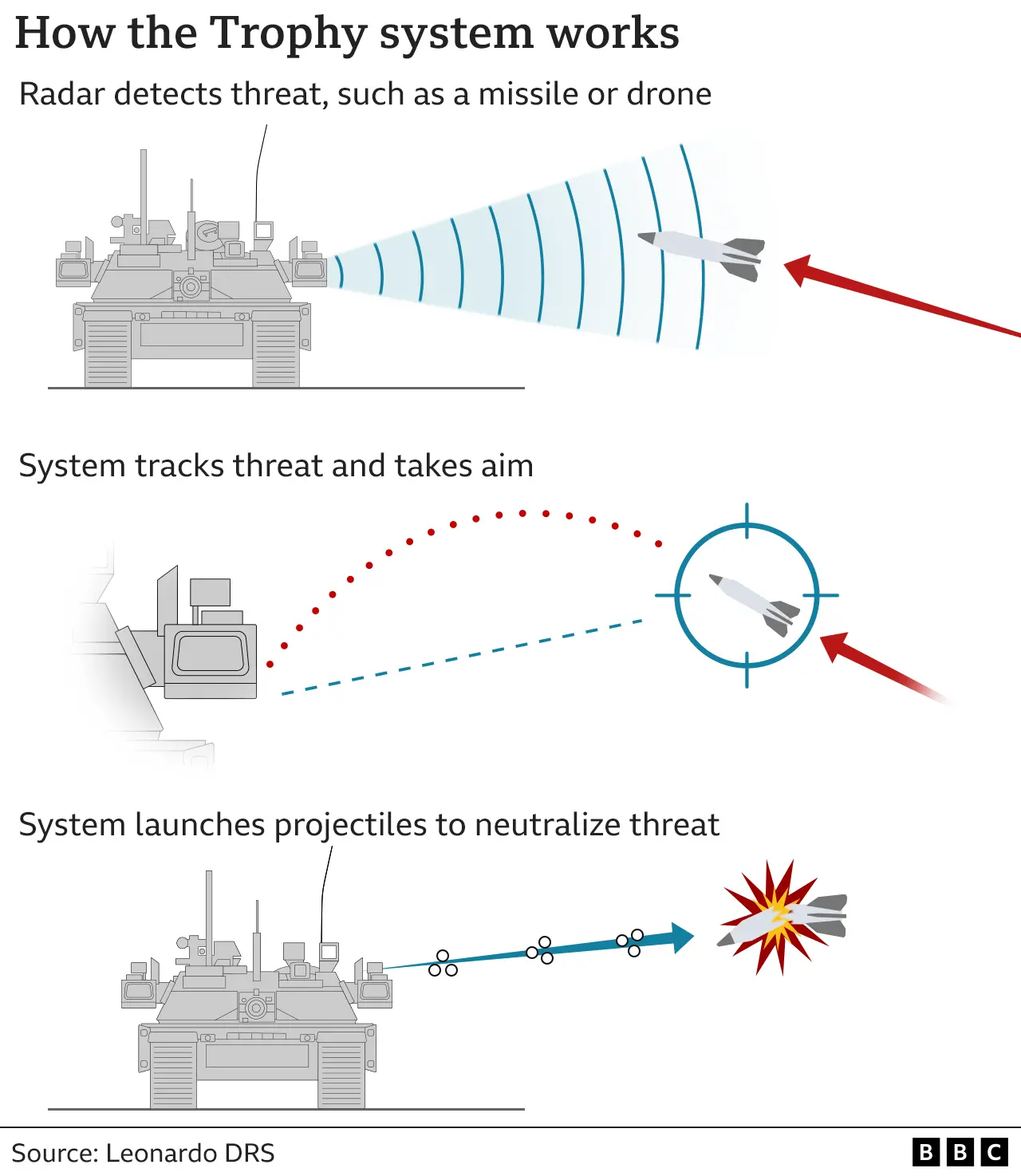

They developed an Active Protection System called Trophy. It works by using radar to track the incoming threat - missile or drone - then a rotating launcher on the turret fires a stream of explosive projectiles, neutralising it before it can hit the tank. Trophy, or a variant of it, is likely to become standard on many of the latest Western tanks.

"Advances in counter-drone measures will reduce the effectiveness of drones that now seem to roam about the battlefield looking for easy targets," says Gen Hodges.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo, does the tank have a future? Or is it, as some predict, doomed for the scrapyard?

"There will always be a need for protected mobile firepower," says Gen Hodges. He predicts a future, not far off, where remote-controlled, unmanned tanks - essentially armoured drones - will be moving across the battlefield in tandem with crewed tanks, increasing their firepower while reducing the risk to life.

"I was an Infantry soldier and I'd never want to be in any fight in any terrain without the benefit of protected, mobile firepower," he says.

Justin Crump, a former British Army tank commander and now CEO of the defence intelligence firm Sibylline, agrees. "Tanks have a firepower, mobility and resilience that Infantry just don't have. It's a flexible platform that can operate day and night, get to the objective and deliver shock to the enemy. Ukraine would not be rebuilding its tank forces if tanks were not vital. They have asked for over twice the number of tanks that the UK possesses."

David Willey has been instructing the British Army and more recently, visiting Ukrainian soldiers. "It's not the best tank that counts, it's the best crew," he says. "The most expensive kit in the world doesn't necessarily mean you're going to win. Belief in your cause is vital, and the Ukrainians believe in their cause."