Burnley's Pastor Mick: ‘If I lock this door, he dies’

BBC

BBCEvery seven seconds - on average - a person was referred for NHS mental health support in England in September. In Burnley, that comes as no surprise to Pastor Mick - a drug-dealer-turned-lifesaver during Covid - who each day meets people struggling to survive.

This article contains several references to suicide.

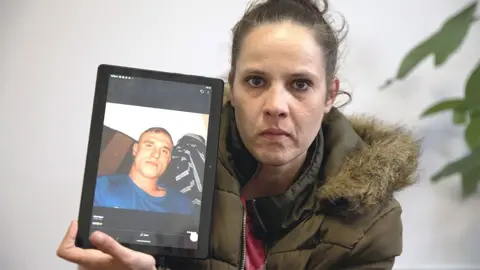

Joanne was shaken to her core 18 months ago when her partner, Robert, died suddenly.

"It feels like it's my fault, because I didn't get the help quick enough for him," she says.

Robert's mental health deteriorated during the first lockdown. He couldn't cope with being stuck at home and developed suicidal thoughts.

Joanne says she rang a mental health team two weeks before his death asking for help - and was told someone would ring Robert the next day. But she says the call never came.

Two weeks later, Robert took his own life.

Joanne is speaking to us in Pastor Mick's new home in the heart of Burnley town centre - a former gym that closed during the pandemic. The building has been reborn as his church - and is called the Church on the Street.

It's a big space. The original showers, lockers and mirrors are still there, but there are crucial new additions. There's a giant wooden cross by an altar and four new office rooms in the corner - used as a private quiet space for qualified mental health counsellors.

It was Joanne who found Robert's body. Later that day, she got a call from the mental health team she'd contacted a fortnight before.

"They were like: 'Can I speak to Robert?'

"I said, 'He's not here no more… he's done the damage.'"

Joanne says the woman on the phone apologised and said they had been very busy. "She said 'I'm so sorry to hear that, I wish I could have got back sooner.'"

Although Joanne doesn't blame the mental health team, she believes Robert could have been saved with early help. "I think he'd have been all right - he'd have still been here."

More than a year on, Joanne is still haunted by death. Each word brings back painful memories, but she wants to share how she is feeling. "I can see the flashbacks. I can see him every day in my head - when I get up, when I go to sleep."

She says one day everything just became too much for her. "I rang Pastor Mick and he told me to come down. He's been great."

Church on the Street has been Joanne's salvation. She says it's a place where she and her family feel safe - and she's not the only one. Hundreds of others come here each week looking for hope.

Sadly, Joanne's story is one Pastor Mick is all too familiar with. When Robert died, he says, two other young men took their lives in streets close to Robert's home. At the time, Mick was regularly handing out food parcels in a car park in Burnley.

"I just couldn't believe what was happening. I knew I'd have to do something more and that I needed somewhere - a home - to deal with the mess and devastation left behind by Covid."

Inside Mick's church - we spent a month there on and off - there's a friendly open-door policy. Mick wants others who have had troubles to find hope - just like he has. In his 20s, Mick was a drug dealer consumed by cocaine and violence. He has now found faith and feeds the poor.

The church is expanding quickly - it has its own food and clothes banks. Mick also liaises with the police, housing organisations, the local council and drug rehabilitation services.

Watch - The Cost of Covid: A Year on the Front Line

"What we are doing here is free. The hot food is free, the coffee is free, the tea is free, the counselling is free," he explains. "We are keeping people alive. Sometimes it just puts it off for another day, but it's another day of life, a lot of them die."

Mick is particularly concerned about the lack of access to mental health care for the most vulnerable - people who find it difficult to see their GPs, let alone get access to a bed in a support facility.

"The help available is negligible, the mental health system is on its backside."

Mick blames the Covid lockdowns and the many months of restrictions for making issues worse. In Burnley, he hears stories of people who, in isolation, have spiralled down - turning to drugs and alcohol.

In September 2021, Lancashire and South Cumbria NHS Foundation Trust says it recorded the highest monthly number of so-called "Section 136" detentions in its area. That's when police detain a person and take them to a place of safety if they appear to have a mental health disorder. There were 196 - more than six a day.

In response, the trust says it has expanded its street triage services for people in crisis - in partnership with the police and ambulance services.

Mick says every other person he meets is struggling with a mental health issue - whether it be anxiety, paranoia or just being unable to cope with everyday life. After a busy day, he closes the church - but then, just before he locks up, his phone rings.

It's another person in need of help - called John. We can make out some of the conversation. He sounds manic, lost and angry and is threatening to kill himself. He believes there has been a great injustice and people are out to get him.

Mick talks to John calmly and compassionately.

"Come and see me. I'm here, I'm waiting for you. There's a brew here for you, we can talk it through."

The deal has been agreed. John won't attempt to take his life and Mick will hang on for him.

"[If] I lock this door, he dies, that's a fact - so the door has to stay open."

When John arrives at the church, he's shouting, sweating and struggling to breathe. It's upsetting to see.

"I know who they are," he says, shaking uncontrollably. "They've been so horrible and nasty towards me. I've just had enough, it's been going on too long."

Mick gently guides him over to the middle of the room.

"Come on, I want you to take a deep breath," says Mick, holding John in his arms. "Take a really deep breath… All right… So tell me what the panic is?"

Fifteen minutes later, John is calmer. His breathing has stabilised and, with a cup of tea, he's eating a slice of warmed-up meat and potato pie. John tells us that just before his crisis he had called his GP panicking for a prescription - but had been told to call back in 48 hours.

John is thankful - there was nowhere else for him to go. "Nobody else has listened - he's the only one," he says pointing at Mick.

Mick says if it hadn't been for BBC reports on his charitable work at the end of 2020, many people in Burnley wouldn't know they could turn to him - and finding a home for his new church might not even have been possible.

"This place is breathing new life, it's helping people. The people who don't make it through the door die."

We catch up with John the next day. He's smiling and like a different person.

"You don't know what to think, what to do, who to speak to," he says. "People look at you like you belong in a lunatic asylum when you speak about your mental health."

But John also reveals he hasn't seen a GP all year and has lost faith in mental health care - describing it as "non-existent". Mick has referred John to the local mental health crisis team, but John has been unable to see them.

The Lancashire and South Cumbria NHS Foundation Trust told us the use of its mental health urgent assessment centres from July to September 2021 was 75% higher than in the last three months of 2020. It also said that community mental health referrals in August this year - at nearly 600 per 100,000 adults - were nearly 50% higher than England's national average.

Those statistics will come as no surprise to Father Alex who, like Pastor Mick, we first met a year ago. In his church, St Matthew's, pews have been replaced by tables and chairs and a place to cook hot food for those in need.

"We have examples of people waiting 16 weeks when they're in crisis for mental health support," he tells us. "So people are being talked off bridges and given crisis care [phone] numbers."

Looking at Demi Lea and her two children - who have come for breakfast at St Matthew's - you'd never think they were struggling. But Demi Lea says she hasn't done a food shop for months and relies on food banks, charity, and handouts.

She first referred herself for mental health support at the end of 2020, got a phone consultation in June and is now on a waiting list for therapy. But in August, her mental health got even worse after the death of her grandmother - who she used to rely on for support.

"I haven't been able to get on top of things - financially it's been tough," she says. "I can barely function."

Since we met, Father Alex has managed to arrange counselling sessions for Demi Lea. She says she's extremely grateful.

Back at the Church on the Street, we sit down again with an exhausted Mick at the end of a busy day. We chat with him and his colleague Kev - a support worker - about the deaths of two young men, rumoured to have taken their own lives the night before. Mick and Kev are shocked but not surprised - although they caution against speculation.

As we talk, just like the night before, there are more emergencies. Over a 30-minute period, Mick gets three panicked phone calls.

The first is from a mum whose son ran away from home saying he was going to kill himself. The second is from another worried mum whose child is also having suicidal thoughts. Mick says the struggle for these families is to be seen quickly by professionals.

Then comes the third call.

If you've been affected by the issues raised in this report, details of organisations offering information and support for addiction and feelings of despair are available via BBC Action Line.

"I can't cope with life, I just don't want to live any more," says a woman's softly spoken voice. "Nobody has listened, I just want to go to sleep and not wake up."

Mick, head in hands, tries to reassure her.

"I know that feeling," says Mick, "but there is a light that is stronger than the darkness. We'll get you in here on Monday, we'll see you."

He then asks if she has taken any medication. "Yes" comes the reply - enough for an overdose. Kev dials for an ambulance straight away on his phone, while Mick keeps her conscious and talking on his.

"I just don't want to live, Mick, I'm in a dark tunnel and can't get out," says the woman. He pleads with her. "There's always hope. Make sure your doors are unlocked."

Mick stays on the line until the paramedics arrive and make sure she is safe. But how has he ended up taking emergency calls? What happens when he can't answer the phone? Is this more than he can cope with?

He tells us there was a missed call one night when he was asleep - and the caller had left a worrying message. "If you don't answer the phone, I'm going to kill myself."

Unfortunately, that person did take their own life, Mick explains - his voice breaking with emotion.

A few days later when we arrive at the church one morning, we meet a man called Robbie who's 29. He has been on the streets all night, but is now sitting in the office going through his possessions - the clothes on his back and a couple of see-through plastic bags.

He's showing Mick the medication he's been prescribed. During lockdown Robbie struggled and began hearing voices. One told him to jump from a well-known bridge in Burnley. Police managed to get to Robbie just in time to stop him and he was admitted to a psychiatric unit.

Since then, he's received six months of expert care at several psychiatric units in Lancashire - something he says has worked well. But yesterday, he was released without accommodation arranged. He says he was told to head to Burnley Borough Council's housing department, but by the time he got there it was closed.

"I just ended up walking around town all night and then as soon as this place opened I just came to Pastor Mick," says Robbie. "Without this place I'd be dead."

Mick is incandescent. He's angry that the money spent on Robbie's care has now been wasted. "He's been released from a psychiatric unit to the street with enough drugs to kill an elephant. It's a tragedy, it doesn't need to be like this."

Robbie begins to get upset. "I feel confusion, suicidal - it's like they've designed it to make me do it because they don't want me here no more. But I'm just trying to better myself. I just want a better life, that's all I want. I'm sick of this."

The next night, Church on the Street paid for Robbie to stay in a hotel. The following night he was placed by Burnley council in a shared room in a B&B above a pub. But within 72 hours he had been readmitted to a psychiatric unit.

During our visits to the church, we talk to Mick's volunteers about the struggle to get mental health support for those who desperately need it - including David Allen, a mental health counsellor with more than 20 years' experience.

"It's not just here in Burnley, it's all over the country. And the ones that suffer most are always at the bottom of the pile. They just feel left behind because they can't get any help." Many self-medicate - he says - with drugs and alcohol.

All of a sudden, in the street outside the church, there's another tense moment. Women scream after a man collapses. "He's OD'd. Help, he's overdosed outside."

Pastor Mick moves quickly. There's now quite a crowd gathered - with children circling on bikes. Two police community support officers are talking into their radios.

But Mick was the first on his hands and knees, talking to the unresponsive man and checking for a pulse. He rushes inside and asks Kev for the Naloxone, a medicine that rapidly reverses the effects of an opioid overdose - such as heroin.

By the time Mick gets back to the man - needle in hand - the panic is over. The emergency medication wasn't needed and the man is back on his feet. Nevertheless it was still a traumatic moment for Mick - and he becomes emotional.

"People don't like to see [moments like] that but that's the reality of every city and every town in this country," he says. "And I'm sorry if it offends people, but they're dying, and they can all be saved, every last one of them."

Pastor Mick and his colleagues are proud with what they have achieved this year - but they also fear what the pandemic might yet bring in terms of mental health problems.

Health economist Dr Luke Munford - from the University of Manchester - says an alarm bell is ringing in many poorer areas of the UK. Urgent and emergency mental health referrals to crisis teams in East Lancashire almost quadrupled when you compare July 2019 to July 2021 - he told us - but the picture is "similarly stark in other deprived parts of the country".

The Lancashire and South Cumbria NHS Foundation Trust says it's receiving £11.6m of NHS funding over three years to help improve community mental health services.

Pastor Mick's transformation from violent drug dealer to lifesaver during a pandemic is profound - a personal redemption. "To be able to serve people who are dying has become the biggest privilege of my life," he says. "I feel the best I've ever felt in my life, I feel free. It's made me a better, stronger person - a softer, gentler person."

NHS England told us they urge anyone who requires help with mental health to come forward.

If you've been affected by the issues raised in this report, details of organisations offering information and support for addiction and feelings of despair are available via BBC Action Line.

Photographs by Phill Edwards