The court orders depriving vulnerable children of their ‘liberty’

BBC

BBCGrowing numbers of very vulnerable children in England are being detained in temporary accommodation under special court orders described as "draconian" by one senior judge.

In a rare move, the BBC has been given access to court proceedings and documents, which reveal the everyday impact these orders have on young people.

Holiday lets, caravans and canal boats, are just some of the temporary locations being used to house children - because there aren't enough suitable places in registered children's homes. Not only are these unsuitable, they are now illegal - unless a court rules otherwise.

Since September, any home for under 16s in care - either permanent or temporary - needs to be Ofsted registered. But because there aren't enough registered places available, councils looking for a way to keep the children in unregistered accommodation without breaking the law, are turning to the family courts to issue Deprivation of Liberty orders. These can allow children to be kept behind locked doors and windows, and even permit the use of medication without consent as a means of restraint.

Here are the stories of a number of teenagers.

She's an "exceptionally intelligent and articulate 15-year-old girl" reads one legal report before the Family Court. The girl can't be named, but is known to legal teams by the initials FJ.

The past year has been traumatic for her. FJ, who has been diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder, went into care 11 months ago after having self-harmed, attempted to take her own life, and having run away from her family home.

She was first placed in a registered children's home, but then made another suicide attempt. Her local authority, the City of York, tried hard to find a safe place for her close to her family home but it was difficult. The council approached 225 other placements, but none would take her.

She has since been housed in three locations, including a secure unit and a holiday cottage with staff.

She's currently in a property where she is watched over by two members of staff day and night. It's not registered with Ofsted - so because of September's change in the law, a Deprivation of Liberty order is needed.

If it was registered, managers would have to be approved, staff checked and buildings inspected.

Children's movements can be restricted in a children's home - particularly if it's a secure unit, but the terms of a Deprivation of Liberty order can be far more stringent. The orders vary from case to case, but generally they restrict a child's freedom and confine them to one location. They could also stop them having contact with a family member or access to a mobile phone. In extreme cases, it could allow them to be sedated.

The orders are not new, but local authorities are increasingly turning to them to accommodate vulnerable children. FJ's order means she cannot meet her friends without an adult present - or freely access the internet.

Despite having obtained the deprivation order, the council is obliged to try to get any property FJ is living in registered as a children's home as soon as possible. But that can be a complex process.

And there is further uncertainty for FJ. York wants to move her soon to another placement which is closer to family and school but the dates for that keep shifting.

FJ feels the local authority is "just not bothering" according to a court document expressing some of her personal feelings. The situation is creating a "heightened state of anxiety, instability and frustration" for her, due to her feelings being "out of control".

Although she has made progress learning to manage those feelings, the document states that future uncertainty is heightening "the risk to herself such as self-injury through cutting, biting, misuse of medication or running away. She can become angry and impulsive which leads to incidents of aggression with others."

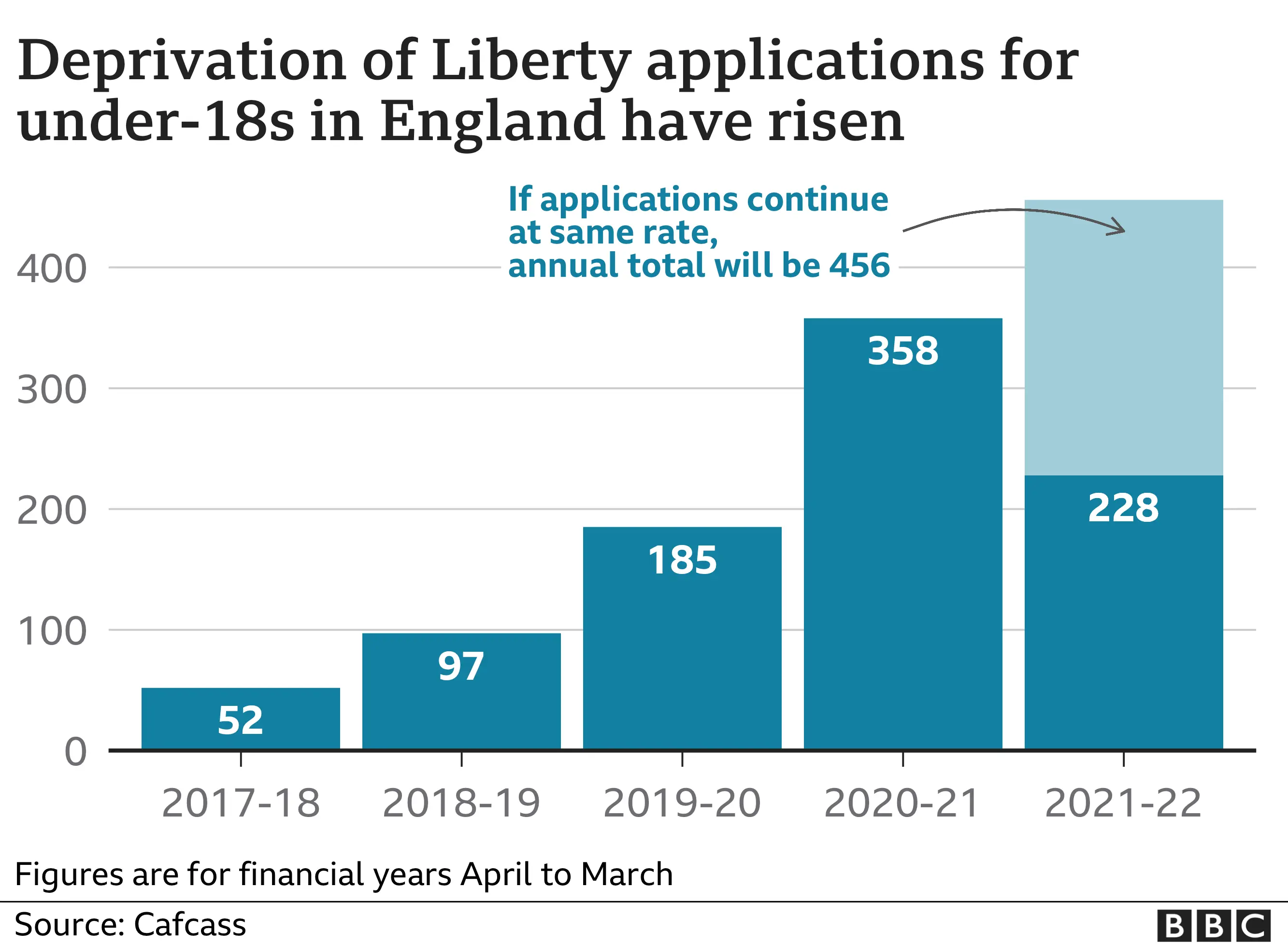

There are scores of vulnerable teenagers in care, who like FJ, are detained in temporary or unregistered accommodation across England and subject to Deprivation of Liberty orders. Data from the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service - Cafcass - shows numbers of applications for such orders have increased starkly in recent years. These figures are likely to be an under-estimate, according to those familiar with these cases.

Judges are concerned about the number of applications appearing before them - and the lack of suitable places for these children.

High Court Judge, Sir Alistair MacDonald, has been hearing FJ's case along with others. It has been his job to decide whether to grant what he describes as these "truly draconian" orders, which have a "profound impact" on each young person.

"These cases are overwhelming the Family Division," warned Mr Justice MacDonald at one hearing.

Another case being heard by him involves a 15-year-old boy from Plymouth - known as QV. His Deprivation of Liberty order has allowed him to be held in a holiday lodge some distance from the city.

Like FJ, he has autism. He also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and Tourette's syndrome. Since being taken into care at the age of five, he has been through more than a dozen placements.

Described as "extremely vulnerable" to abuse and exploitation, he had to move from his last children's home in September after he climbed onto a roof and started throwing things down to the street below. While living In another placement, he discussed how to make a bomb.

In the lodge, QV was being supervised day and night by two members of staff - similar to FJ. The court heard he felt isolated and had been refusing to attend the schooling arranged for him.

One of his social workers said that because the property was a short-term holiday rental, it did not have the "safeguards you would expect in a formal children's home setting". Then, because the lodge had already been booked for October half term, QV had to be moved again, to another property in a different holiday park.

If QV was a year older, the rules would be different. Local councils have to provide accommodation for 16- and 17-year-olds, but they can be housed in so-called "unregulated" settings which don't have to be registered with Ofsted. These settings are not children's homes, but are usually rooms or flats where older teenagers - on the verge of independence - learn to look after themselves. But in QV's case, it is likely special measures would almost certainly still apply to someone so vulnerable.

In 2020, 6,480 under-18s were living in unregulated settings - the vast majority aged 16 or 17.

Ofsted describes the problems housing teenagers who need high levels of support as "very worrying" with children exposed "to a risk of serious harm".

Its National Director for Social Care, Yvette Stanley, also says placing young people in unregistered properties is costly - with local authorities paying around £10,000 per week per child.

"This shows it's not about local authorities skimping... there's just not enough provision out there."

Young people with the most complex needs are arguably best housed in secure units - at least for a time. But across England, there are only 13 such facilities with a maximum of 234 spaces.

The urgent referral list for secure places has reached record levels, as Mr Justice Macdonald noted in his 3 November judgment for FJ and QV:

"As of 14 October 2021, there were 58 live referrals for children requiring secure accommodation and only 6 projected beds."

And, as the City of York discovered when they sought a place in an ordinary (rather than secure) children's home for FJ, many are reluctant to take the most vulnerable children.

In England:

- There are 80,000 or so under-18s in care

- Most live with foster parents

- Nearly 13,000 are in children's homes

- More than 2,700 homes are Ofsted-registered

- Courts are seeing almost double the number of cases involving 10- to 17-year-olds compared to nearly a decade ago

Each statistic is a real child with a personal story to tell. Children like FJ in York, QV in Plymouth and the third teenager from Derby - whose cases have all been considered by Mr Justice MacDonald.

Both York and Derby councils said they were working with providers to get the unregistered placements registered as quickly as they could.

But in his recent judgment, Mr Justice MacDonald wrote there was "no clear evidence" that registration was achievable for the Derby home - and in York, timescales were "opaque" for both FJ's current and future homes to be registered.

Plymouth Council was not trying to register either of the holiday lodges with Ofsted - but just wanted to keep QV in them until a secure-home place became available.

Mr Justice MacDonald also expressed his concern at how judges - without "institutional expertise" or the power to deploy inspectors - were being asked to decide children's futures.

"The High Court is not a regulatory body and nor is it equipped to perform the role of one," he wrote.

Covid has exacerbated an already difficult situation for local authorities, says Charlotte Ramsden, Chair of the Association of Directors of Children's Services (ADCS). She says there is now a "complex cohort of deeply distressed and traumatised teenagers".

"Changing the law in September has been like closing a safety valve on a pressure cooker that's being heated. It explodes when we get these crisis placements - putting children in Airbnb or holiday lets - because there's nowhere else to place them."

She says the fact no-one will take these young people is "keeping a lot of us awake at night".

Both Ofsted and ADCS say a new type of provision is needed for these young people - a combination of health and social care.

The Department for Education told us it was up to councils to provide suitable safe accommodation for vulnerable children in their care and the chancellor had announced investment to help them. It also noted that the current independent review of children's social care, led by Josh MacAlister, would be looking at the "major challenges" for the sector.

In recent months, Mr Justice MacDonald has heard other cases involving the most vulnerable children who needed, but hadn't been given, suitable care.

In July, he heard about a 15-year-old girl from North Yorkshire who was self-harming every day and had to be restrained nearly 200 times in just over six months. Doctors said she needed to be in a secure hospital, but there were no specialist NHS beds available anywhere in England.

That same month, he was asked to deprive a 12-year-old boy of his liberty who Wigan Council had placed on a regular hospital ward. The boy was so angry and violent it took 13 police officers to restrain him and he had to be sedated. Mr Justice MacDonald refused that order - and Wigan had to find an alternative.

Information and support

If you or someone you know needs support for issues about emotional distress, these organisations may be able to help.

What has happened to QV and FJ the two 15-year-olds whose cases ended up in the Family Division of the High Court?

The boy has now been moved out of the holiday park and into a house in a small town, still with staff supporting and supervising him and he is still deprived of his liberty. Plymouth Council is seeking to register the property with Ofsted.

In the case of FJ, Mr Justice MacDonald has called York back to the High Court to check the Ofsted-registration process for the two homes - current and planned. He has repeatedly mentioned the impact all the uncertainty must be having on her.

"[The girl] worries about the question of registration and lawfulness... this has a concrete impact upon her mental health."

Images in artwork courtesy Getty Images