The black children wrongly sent to 'special' schools in the 1970s

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan Productions

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan ProductionsIn 1960s and 70s Britain, hundreds of black children were labelled as "educationally subnormal", and wrongly sent to schools for pupils who were deemed to have low intelligence. For the first time, some former pupils have spoken about their experiences for a new BBC documentary.

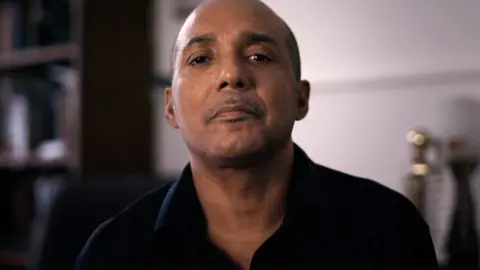

In the 1970s, at the age of six, Noel Gordon was sent to what was known at the time as an "educationally subnormal" (ESN) boarding school, 15 miles (24km) from his home.

"That school was hell," says Noel. "I spent 10 years there, and when I left at 16, I couldn't even get a job because I couldn't spell or fill out a job application."

About a year before joining the ESN school, Noel had been admitted to hospital to have a tooth removed. He was given an anaesthetic, but it transpired that Noel had undiagnosed sickle cell anaemia, and the anaesthetic triggered a serious reaction.

Noel says the resulting health issues led to him being perceived as having learning disabilities and being recommended for a "special school". Yet no evidence or explanation of his disability was ever given to him or his parents.

"Someone came and said they'd found "a special boarding school with a matron where they'd take care of my medical needs", says Noel.

During that conversation they also said Noel was "a dunce. Stupid."

But Noel's parents were not made aware that his new school was for the so-called educationally subnormal. They had moved to England from Jamaica in the early '60s and had high expectations for their son's education.

During his first night at the boarding school, six-year-old Noel lay alone in bed, crying for his mum. The school felt cold and institutional.

"I can still smell the old wooden flip desks. Oh, and being racially abused on my first day," he says.

A student hurled racial slurs at him in the classroom but wasn't reprimanded - the teacher simply told him to sit down.

The school didn't teach a curriculum. Although Noel was given a book to write in by a teacher, he was never taught basic grammar or how to spell. He did some basic addition and subtraction but during classes, he mainly did crafts and played games.

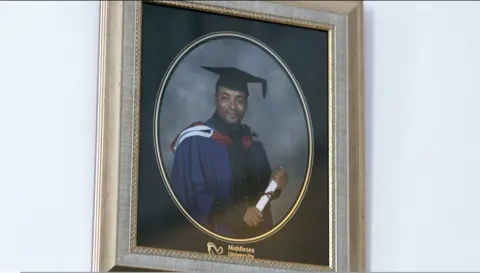

Noel Gordon

Noel GordonHis parents only realised what kind of school it was when Noel, then seven, was punched by a 15-year-old boy, and his father visited for the first time.

Noel recalls his father saying to the headmaster, "This is a school for handicapped children" - using an outdated term. He says the headmaster replied, "Yeah, but we don't like to use that word, we call them slow learners."

The realisation was devastating, but Noel's father felt powerless to change things.

Noel wasn't given the chance to take exams and get qualifications. On reflection, he says being labelled educationally subnormal made him feel inferior for the rest of his life, and gave him a lot of psychological problems.

"Leaving school without any qualifications is one thing, but leaving school thinking you're stupid is a different ball game altogether. It knocks your confidence," he says.

A new BBC documentary tells the story of how black parents, teachers and activists banded together to force the education system to change.

- You can watch Subnormal: A British Scandal on BBC1 on Thursday 20 May at 21:00 or watch on iPlayer

The term "educationally subnormal" derived from the 1944 Education Act and was used to define those thought to have limited intellectual ability.

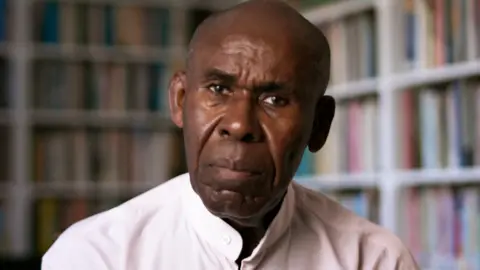

"That label made children feel inferior," says education campaigner Prof Gus John, who came to the UK from Grenada in 1964 as a student, and soon became aware of the issue.

"Students from ESN schools wouldn't go on to college or university. If they were lucky, they'd become a labourer. The term was paralysing and killed any sense of self-confidence and ambition."

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan Productions

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan ProductionsPrimary and secondary ESN schools categorised children as having moderate learning disabilities, severe learning disabilities or being "un-teachable".

These categories were broad and when students were recommended for ESN schools, robust reasons weren't always given by teachers and psychologists.

While some ESN schools did have good examples of teaching, for many pupils, their needs were overlooked.

Black students were sent to these schools in significantly higher proportions. The documentary makers have seen a 1967 report from the now-defunct Inner London Education Authority (ILEA), which showed that the proportion of black immigrant children in ESN schools (28%) was double that of those in mainstream schools (15%).

"The percentage of black children in ESN schools relative to black students in normal schools was scandalous," says Gus John.

But why were so many black children defined as subnormal?

Figures from the 1960s and '70s show that on average, the academic performance of black children was lower than their white counterparts. This fuelled a widespread belief that black children were intellectually inferior to white people.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA leaked local authority report in 1969, written by a head teacher called Alfred Doulton, argued that West Indian children in general had lower IQs. This claim was based on the results of IQ tests that were commonly taken by primary school children at the time.

One of the key proponents of such theories was Hans Eysenck, a former professor at the Institute of Psychiatry at Kings College London. He believed intelligence was genetically determined and cited a US study that seemed to show that the IQ of black children fell, on average, 12 points below white children.

As Gus John says in the documentary: "When people like Eysenck wrote about race and intelligence, what they were actually doing was justifying all those tropes that had been floating around throughout the period of enslavement, where people believed that not only were black people sub-human... but they can't be expected to perform or to be as intelligent as white people."

Many teachers saw black children as intellectually inferior, and feared that too many black pupils in a class would depress the attainment of white pupils.

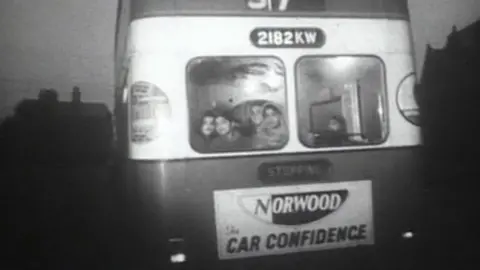

Following a protest by white parents in Southall, west London, in June 1965 the government issued guidance which underlined the social, language and possible medical needs of immigrant children, and suggested maintaining a limit of about 30% of immigrants in any one school.

As a consequence, many local authorities adopted the policy of bussing - sending immigrant children to schools outside their local area in an attempt to limit the number of ethnic minorities in schools. The practice finally ended in 1980.

"The education system fuelled and legitimised the idea that black Caribbean children were less intelligent than other children. This was why so many of them ended up at ESN schools. It was rampant racism," says Gus John.

Many wrongly equated race with intellectual ability. But as the late educational psychologist Mollie Hunte argued, the generally poor attainment of black students wasn't because of their intellectual ability. Instead, the tests used to assess pupils at the time were culturally biased.

As Gus John explains, the tests used references and vocabulary that newly-arrived Caribbean children were unfamiliar with.

"A key element was language," says Prof John. "If you grew up in a Jamaican household, you'd use Jamaican English - patois or creole. The problem most Caribbean students had was that because it was a derivative of standard English, nobody believed that black students needed language support."

As a result, they were not given the extra help other immigrant children, who spoke no English before they arrived, received.

According to Prof John, teachers didn't try to understand the cultural barriers black children faced, and the assessments didn't consider their domestic and socioeconomic circumstances - or the impact of migration. Many children would travel to the UK only once their parents had settled in. They arrived in an unfamiliar country to live with virtual strangers, who they had not seen for years.

"This displacement and movement caused a lot of trauma," says Prof John. "There was grief and bereavement. Those children would often not see their grandparents again."

According to the education campaigner, there was a culture of low expectations among teachers. Learning difficulties were mistaken as learning disabilities and black children were simply "written off" and sent to ESN schools.

That is what happened to Maisie Barrett from Leeds, who was sent to an ESN school at the age of seven in the 1960s.

"I initially went to a mainstream school. There, a teacher told my mother that I was 'backwards' and couldn't learn. We were told that I'd be better off at a special school."

Maisie Barrett

Maisie Barrett

Maisie says that the decision to send her to an ESN school was a mistake that ruined her life chances. Like Noel, she wasn't taught a curriculum.

"We played games, had discos… I call it a 'free school' because the education was so basic and we played a lot more than we worked," she says.

It was only in her 30s, decades after being sent to the ESN school, that Maisie was diagnosed with dyslexia.

"Rather than help me with my learning difficulties, I was simply dismissed as stupid. Teachers never took the time to find out why I struggled with learning. That messed up my confidence," she says.

"I was slow, but a teacher should have taken the time to help me learn."

According to Maisie, the lack of learning and support was only part of the problem.

"I went to a school that was a racist institution," she says.

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan Productions

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan ProductionsBoth Noel and Maisie were eventually offered the chance to attend mainstream schools. By then however, it was too little too late.

In Noel's case, he went to a local secondary school on a part-time basis from the age of 12 and spent the rest of the week at the ESN school.

"At the part-time secondary school, I would truant because of the intimidation of not having friends and not being able to read," says Noel.

Maisie left her ESN school at the age of 13 and started at mainstream secondary school.

"My mum put me in touch with a black social worker who, after assessing me, said that I was intelligent and suggested that I was placed in the ESN school because of racism," says Maisie.

By then, however, unable to read or write, Maisie found secondary school extremely challenging and she left with no qualifications.

Initially, many Caribbeans who migrated to the UK during the 1960s and '70s, had a favourable view of ESN schools. Often referred to as "special schools" by teachers, Caribbean parents, with little understanding of the British education system, thought these schools would provide better support and learning for their children.

"When my mother was told that I'd been recommended for a special school, I remember her smiling. She thought that a special school meant a better school," says Maisie.

This presumption about "special" schools was also informed by Caribbeans' experiences of schools back home.

"British education was seen as a route to social mobility and the aspirations of parents were very high," says Gus John. "Teachers had a high profile in Caribbean communities, and parents initially trusted British teachers. It was a shock to find out that their children were being defined as subnormal."

However, concerns soon developed among Caribbean parents. As they witnessed their children struggle with the basics of reading and writing, parent and action groups emerged.

For example in 1970, after discovering that there was a disproportionately high number of black children in ESN schools in north London, a group called the North London West Indian Association formally complained to the Race Relations Board - alleging discrimination under the 1968 Race Relations Act.

Allow X content?

In 1971, a book called "How the West Indian Child is Made Educationally Subnormal in the British School System", proved instrumental in shifting the opinion of black parents. The author, Grenadan writer and teacher Bernard Coard, taught in an ESN school and had noticed the high number of Caribbean children there. When a group of concerned parents asked him to look into the issue, he wrote the book in record time.

He argued that ESN schools were being used by the education authorities as a "dumping ground" for black children, and that teachers were mistaking the trauma caused by immigration for a lack of intelligence.

Lyttanya Shannon/ Rogan Productions

Lyttanya Shannon/ Rogan ProductionsBernard Coard's seminal work led to positive action, and a sharp rise in black supplementary schools. These were Saturday schools set up by black parents with the aim of raising the educational attainment of black children. They would teach curriculum subjects alongside black history, to raise the self-esteem of children, to help them gain qualifications and prepare them for employment.

Following years of pressure and campaigning, the 1981 Education Act enshrined inclusivity in law and the term "educationally subnormal" was abolished as a defining category.

A government enquiry into the education of children from ethnic minority groups published in 1985 found that the low average IQ scores of West Indian children were not a significant factor in their low academic performance. Instead, racial prejudice in society at large was found to play a crucial role in their academic underachievement.

But for both Noel and Maisie, the impact from their time at ESN schools remains.

"The ESN label crippled my confidence. I could have been anybody - but I was never given the tools to be the person I was born to be," says Maisie.

Despite writing two books and gaining four degrees after leaving school - including in Caribbean studies and creative writing - Maisie has struggled to find work over the years. Currently unemployed with two adult children, she did work as a dyslexic support worker but was made redundant a few years ago.

Maisie feels as if she has spent her life "catching up", ever since leaving the ESN school.

Noel discovered he actually likes learning and has accumulated a number of impressive qualifications as an adult, including a degree in computing. His wall at home in Tottenham is covered in certificates. Nevertheless, he still struggles with his reading and writing.

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan Productions

Lyttanya Shannon/Rogan Productions"That ESN school has messed me up," says Noel.

And despite significant progress since then, disparities in the education of black children remain. "The concerns we used to have about ESN are still very much with us now in terms of the number of black children being put into pupil referral units," says Gus John.

Pupil referral units were set up in 1993 to teach children excluded from mainstream school. But black pupils are disproportionately hit with fixed-term exclusions in England - by three times as many in some places.

As Prof Gus John considers the long-term impact of ESN schools, his biggest regret is that "a whole generation were dissuaded from dreaming big".

- You can watch Subnormal: A British Scandal on BBC1 on Thursday 20 May at 21:00 or watch on iPlayer

- The documentary follows on from Steve McQueen's film Education, part of his critically acclaimed mini-series Small Axe

You may also be interested in:

In August 1970, nine people would end up at the Old Bailey in a high-profile trial that secured an important spot in the timeline of black British people.