Prince Philip: A turbulent childhood stalked by exile, mental illness and death

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPrince Philip is being remembered as the longest-serving consort in British history, who sacrificed a naval career to give steadfast support to his wife. But it is easy to forget he had endured an exceptionally turbulent childhood, writes historian Philip Eade.

He was abruptly separated from his parents and four elder sisters at the age of eight, and destined never again to live in the same home as his immediate family.

In later years, while out and about on royal duties, he would gain a reputation for his quizzical, ragging and, at times, startlingly blunt remarks. And to friends, his emotional reserve was every bit as striking as his bluff, no-nonsense exterior.

His tendency to hide his feelings meant that even those who knew him well were occasionally taken aback by his bouts of prickliness - presumed to be legacies of his unsettled early life.

Prince Philip was born in Corfu in 1921 eight years after the assassination of his grandfather, King George I of Greece.

He was the youngest child and only son of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and Princess Alice of Battenberg.

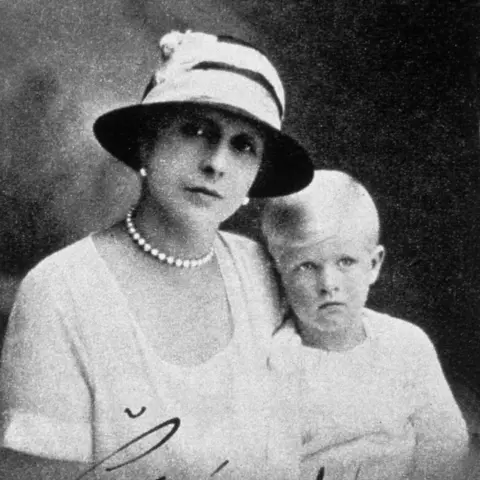

Mary Evans Picture Library

Mary Evans Picture LibraryHe was little more than a year old when his father was sent into exile by an army court martial following Greece's calamitous defeat in a war with Turkey.

The family's subsequent flight across the Adriatic Sea to Italy aboard a British warship, with the infant Philip sleeping in a converted orange crate, was helped by King George V of the UK, Andrew's first cousin. The monarch's determination to rescue them owed much to his regret at having failed to save another first cousin, Tsar Nicholas II, during the Russian Revolution five years earlier.

Eventually, the family settled on the outskirts of Paris at St-Cloud, in a garden cottage owned by Philip's aunt. Philip attended a small day school nearby, but in 1930 his world was again thrown apart when his mother, whom he had always adored, suffered a severe mental breakdown.

PA Media

PA Media

PA Media

PA Media

Mary Evans Picture Library

Mary Evans Picture Library

Alice, who was the daughter of Prince Louis of Battenberg (whose family name was anglicised to Mountbatten during World War One), had been born profoundly deaf. She learned to lip-read in several different languages.

Brave, energetic and determined not to let disability hold her back, she had served as a latter-day Florence Nightingale during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, setting up and nursing in front-line hospitals.

Three decades later, during the war-time Nazi German occupation of Greece, she hid Jews in her house in Athens, earning, like Oskar Schindler, Israel's award of Righteous Among the Nations.

In the years immediately after the family's flight from Greece, however, her behaviour had grown disturbingly strange. One doctor who saw her, diagnosed her as a paranoid schizophrenic who believed that she was the only woman on Earth, and married to Christ.

Eventually, Alice's mother (Philip's grandmother) bowed to the advice of psychiatrists, and agreed that her daughter should be committed to a secure sanatorium. So she arranged - while the family was staying for Easter 1930 with Alice's uncle, the Grand Duke of Hesse - for a doctor to arrive one day while the children were out. He would forcibly sedate Alice, bundle her into a car and drive her off to a clinic near Lake Constance.

The committal of Philip's mother, on 2 May, marked the end of his family life, although he and his sisters would not have realised this when they arrived back at the grand-ducal palace that evening to find their mother gone.

Alice and Andrew's marriage had been under strain for several years but it, in effect, ended at that point. They hardly saw each other from then on, although they would never divorce.

Andrew stopped acting as her husband. He freed himself from many of his responsibilities as father too, shutting up the family home at St-Cloud and thereafter leading a rather aimless life, drifting between Paris, Monte Carlo and Germany, interspersed with sporadic fruitless interventions in Greek affairs.

He saw Philip now and again during the school holidays, but otherwise left him in the care of Alice's family, the Milford Havens and Mountbattens, in England.

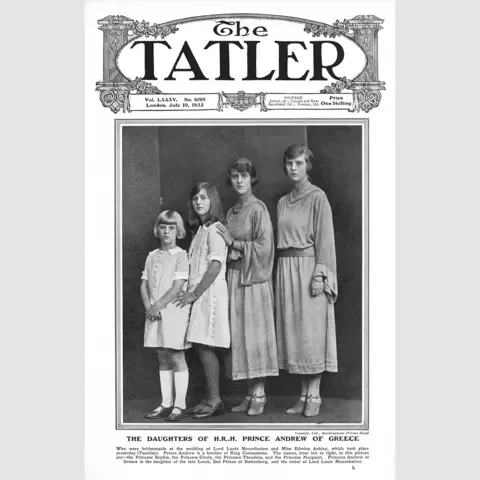

Within 18 months of the family break-up, Philip's sisters were all married to German princelings, so the disappearance of both their parents was of far less consequence for them than it was for their eight-year-old brother.

Mary Evans Picture Library

Mary Evans Picture Library

First, he lived with his maternal grandmother at Kensington Palace, before moving in with his uncle, Alice's elder brother George, the Marquess of Milford Haven - whose son David would become Philip's closest childhood friend (and later best man).

For the next eight years, "Uncle Georgie" acted as Philip's guardian, turning up in loco parentis at school prize-givings and sports days. During some school holidays, he provided a home for Philip at Lynden Manor, on the Thames between Windsor and Maidenhead.

Philip only saw his mother a handful of times during the first two years of her confinement.

At the sanatorium, Alice was told her son would be going to boarding school at Cheam in England - her daughter Cecilie careful to reassure her that, although at first nervous at the idea, Philip had become "thrilled" at the prospect.

For five years, from the summer of 1932 to the spring of 1937 - by which time she had largely recovered her equilibrium - Philip neither saw nor heard from his mother at all. It was not in his nature to overstate the effect of all this. "I just had to get on with it," he later told one biographer.

"You do. One does."

Getty Images

Getty Images

Yet being separated from his mother at such a critical stage in his upbringing undoubtedly left its mark.

However fond he was of his grandmother, uncle and aunt, and appreciative of the homes they provided him, they could never make up for the family home he had lost.

When an interviewer asked him what language he had spoken at home as a boy, his immediate and rather cross retort was: "What do you mean, 'at home'?"

His apparent way of coping was to banish introspection and remain cheerful and purposeful. In the absence of his own father, various surrogates helped shape the young prince's increasingly forthright character.

The headmaster of Cheam was a cheerful clergyman and staunch disciplinarian who used a cane to punish daytime offences and a sawn-off cricket bat for those caught having pillow fights after lights out.

Philip's first beating as a new boy prompted him to ask the headmaster's wife: "Do you like Mr Taylor?" The experienced Mrs Taylor countered expertly. "Do you, Philip?" she asked. "No," answered the boy unequivocally. "I do not."

But as time passed, Philip grew to like not only Mr Taylor but also everything else about Cheam, the tough regime of which he later extolled in a preface to a history of the school: "Children may be indulged at home, but school is expected to be a Spartan and disciplined experience in the process of developing into self-controlled, considerate and independent adults. The system may have its eccentricities, but there can be little doubt that these are far outweighed by its values."

His more timid and sensitive son, Prince Charles, who had a miserable time at Cheam, may not have entirely agreed with this assessment. He also found it impossible to share his father's enthusiasm for Gordonstoun, an even more Spartan educational establishment in Moray, where Philip went at the age of 13 and eventually rose to be head boy.

Philip's housemaster at Gordonstoun, Robert Chew, was also in charge of "character building" at the school during its early years. By the time Prince Charles was sent there, Chew had risen to headmaster and Charles later shuddered when he remembered him as "a remote and austere character who adhered to the founder's beliefs with the conviction of a true disciple".

The founder he referred to was Kurt Hahn, an eccentric Jewish emigre from Salem School in Germany, where Philip had spent a year just after the rise of Hitler in 1933-34.

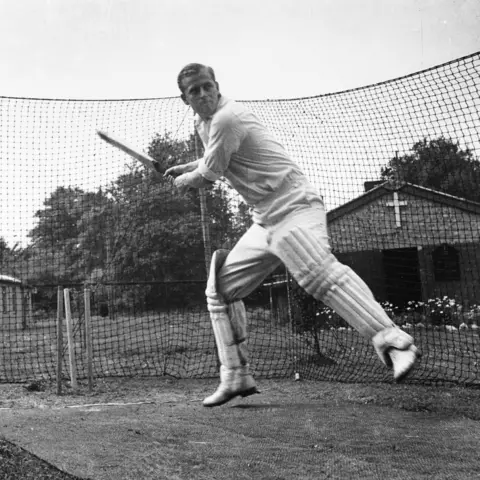

Getty Images

Getty Images

PA Media

PA MediaHahn, the prince's most influential mentor during his time at Gordonstoun, pitted his young charges against what he declared was a five-fold decay of civilisation - the decay of fitness, the decay of initiative and enterprise, the decay of care and skill, the decay of self-discipline, and the decay of compassion.

Hahn and Gordonstoun provided Prince Philip with a much-needed sense of stability after the various upheavals of his childhood. But his later years there were overshadowed by the death of his sister Cecilie, and her family, in a plane crash on their way to London for a family wedding in 1937.

It fell to Hahn to break the news to 16-year-old Philip, who would never forget the "profound shock" with which he listened in the headmaster's study to what had happened.

Perhaps more resilient than most boys due to the various other blows he had suffered before that, he "did not break down", so his headmaster later recorded. "His sorrow was that of a man."

Six months later, Philip suffered yet more sorrow when his guardian Georgie Milford Haven died from cancer at the age of 45.

An obscure figure in most accounts of the Mountbatten family, in terms of sheer intelligence and ability and charm, Georgie was as remarkable as any of them.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the age of 10, he set up a workshop at his father's castle, equipped with lathes, a forge and foundry. So it was no surprise that as a young naval officer, he would go on to design a system of fans, radiators and thermostats for air-conditioning his quarters. He even fashioned a device, controlled by an alarm clock, for making his early morning tea - 20 years before such a gadget appeared on the market.

His remarkable ingenuity helped fire his nephew Philip's budding interest in invention and design, and when Philip grew up, he too would be forever in search of the latest gadgets.

Many who knew Georgie had confidently predicted a brilliant career, and that he would, like his father, eventually succeed to the position of First Sea Lord. But he lacked the obsessive zeal and ambition that characterised his more dazzling younger brother, Louis Mountbatten, known in the family as "Dickie", who now stepped in and took over what remained of the job of bringing their nephew up.

Mountbatten later maintained that he had already marked Philip down as "an exceptional person", the telling moment having been "out shooting one day, when he was eight or nine. It was rough. The way he coped, told me."

Having no son of his own served to focus Mountbatten's attention on his nephew and, although Philip occasionally bridled at his uncle's often showy assumption of parental responsibility, there is no doubt that he had an important influence on him. It was Mountbatten who steered Philip away from his original intention to become a fighter pilot and towards a career in the Royal Navy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMost crucially, it was his uncle who arranged for Philip to entertain Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret on the eve of war in 1939, during a royal visit to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth. By this time, Philip was a cadet there.

It was on this occasion that Princess Elizabeth famously fell in love with the handsome young prince, and she never appears to have contemplated marrying anyone else.

She was only 13 at the time, however, and it wasn't until several years later, while on leave from active service and staying at Windsor for Christmas 1943, that Prince Philip, five years her senior, first showed signs of reciprocating her feelings.

The romance began in earnest soon after the end of the war, and it is generally assumed that he proposed to her while staying at Balmoral in the summer of 1946.

King George VI was at first far from eager to give his consent, not least since several of his closest friends were vehemently opposed to Philip. They whispered darkly about his "Teutonic strain" and suspected that his uncle Louis Mountbatten, a notorious intriguer, was proposing to use him as a Trojan horse to help bring the monarchy more into line with his own "rather pink" political outlook.

Mountbatten had long been viewed by courtiers as unsound on account of his friendliness with Labour politicians such as Tom Driberg - not to mention Mountbatten's notoriously left-wing wife, Edwina.

But the King's misgivings about the prospective match had far more to do with his reluctance to break up his close family unit - "Us Four", as he called them - so soon after the war, and to lose his beloved eldest daughter at such a young age.

For Prince Philip, on the other hand, the prospect of marriage to Princess Elizabeth offered the chance at long last for him to regain the family life that he had lost at the age of eight.

PA Media

PA Media

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne of his more telling thank-you letters to Queen Elizabeth, after staying with the Royal Family, bore moving testimony to how much he relished "the simple enjoyment of family pleasures and amusements and the feeling that I am welcome to share them".

Having been deprived of these "simple pleasures" at such a young age, he was understandably eager now to start a family of his own.

His raising of that family - the Royal Family - stands alongside his support for the Queen and modernising influence on the monarchy as his most important legacies.

- Philip Eade is the author of Young Prince Philip: His Turbulent Early Life