Covid quarantine breakers: 'It was selfish but I don't regret it'

Across the UK, normally law-abiding people are harbouring a guilty secret.

They are the Covid holiday quarantine-breakers.

They travelled to holiday spots where the beaches were drenched in sun and where coronavirus infections were starting to surge.

When they came home, they didn't shut themselves away for a fortnight. Instead, they broke the law.

We don't know how many people have been ignoring the self-isolation law after coming back from a Covid-19 hotspot. But rates of infection from people who have recently travelled overseas, have been rising, says the Office for National Statistics.

But it's clear - anecdotally at least - that lots of people have avoided being caught.

In July, Alice, a 20-something office worker from Surrey, was fed up with not having got away on holiday. For the good of her own mental wellbeing, she says, she broke the rules. Sitting in her garden, she confessed her crime to me.

She'd booked a trip to Majorca with a friend. Then, days before she had been due to fly out, the UK slapped quarantine rules on Spain.

"We were basically told by the holiday company that we wouldn't get our money back. I didn't want to lose another holiday and any money. So just decided to go anyway."

When Alice got to Majorca, she decided the self-isolation she'd face on return to the UK would be a nonsense. The hotel was largely empty and reassuringly clean.

"There wasn't really a time, other than when you were eating, on a sunbed, or in your hotel room that you weren't wearing a mask," she says. "It just felt really safe." Alice believed that the virus transmission rate was very low. She was probably safer in Majorca than England, she thought. In fact, the coronavirus infection rate in Majorca had been climbing rapidly during her stay - meaning her risk of catching it had been growing by the day.

So what happened when Alice returned home?

While her job allowed her to work from home, she wondered about the rest of her life.

"So..." she begins, hesitantly, "I isolated for a couple of days. And then I just thought, you know what, I'm fine."

In the fortnight that followed, the critical period of potential transmission, Alice visited family (although not elderly relatives), went on shopping trips and met up with friends in their homes, or a local park.

"I just thought, if I'm going to catch it anywhere [it will be] in England... people aren't following all the rules all the time."

And you were one of them, I point out.

"Yeah," she replies nervously.

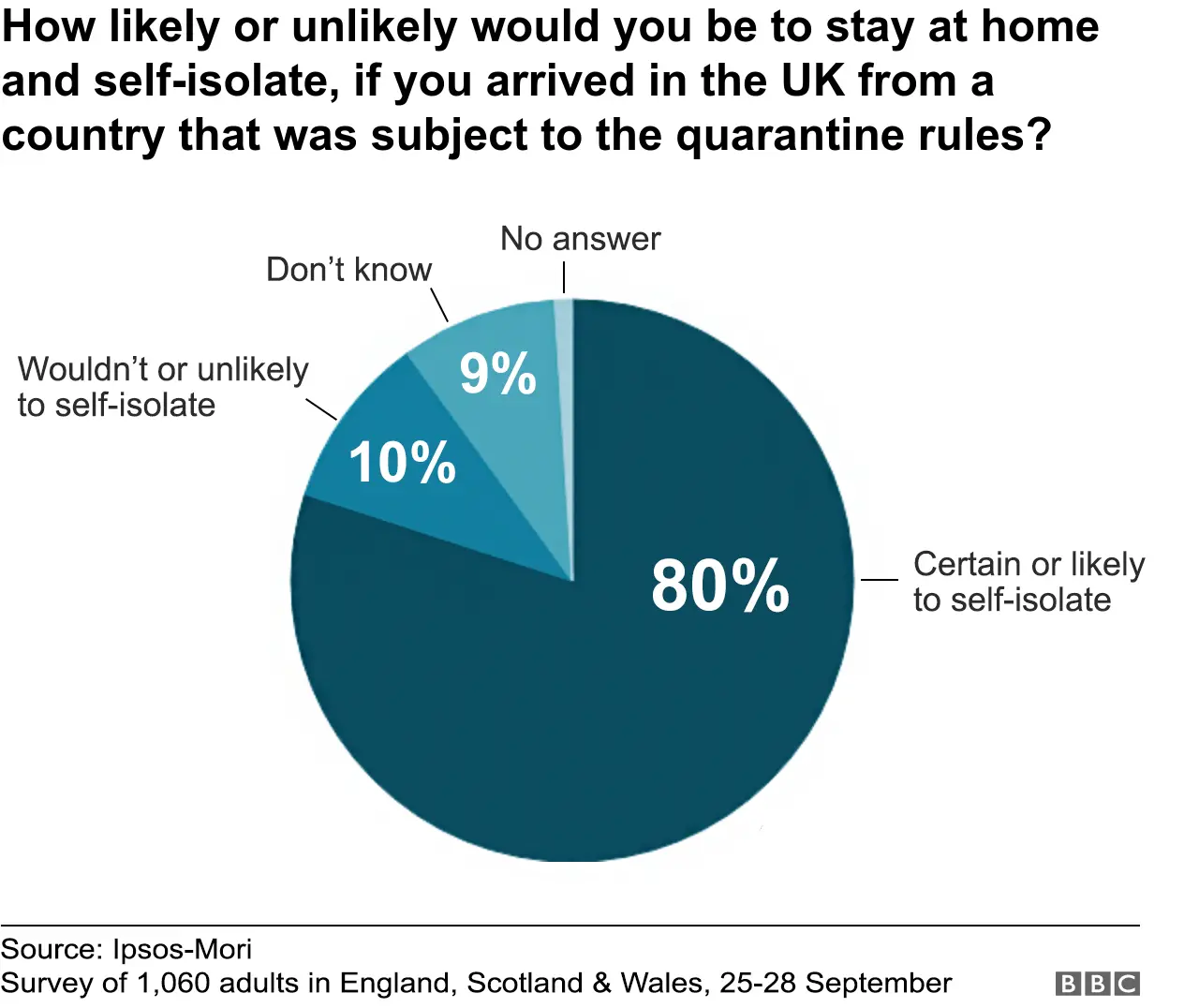

She is not alone. Research organised by the BBC last weekend, suggests a hardcore minority of people were not prepared to obey rules on staying at home if the law required. While only 4% of people polled by Ipsos-Mori said they were "very unlikely" or "certain not" to isolate if they tested positive, that rose to 8% for the under 34s. Asked what they would do if they were told by NHS Track and Trace to self-isolate, because they had been in close contact with someone who had tested positive, the refuseniks across all ages climbed to 8%.

On travel, one in 10 said they wouldn't self-isolate after returning from a hot spot - rising to 16% among the under 34s. Meanwhile, a fifth of people said it was acceptable to break the law to go to work - and a quarter said they'd ignore the post-travel quarantine to care for someone in a different household.

How many breaches have there been?

The latest figures from the police reveal evidence of breaches - but also a lack of clarity of how many refuseniks there really are.

Since March there have been almost 19,000 penalty notices - the Covid equivalent of a parking ticket - for breaching the health regulations.

That's not a great deal in a country the size of the UK - but, interestingly, only half have actually been paid. And that means there are an awful lot of people who have either not recognised what they have done, forgotten about them, or are simply refusing to comply.

Since the introduction of the travel quarantine regime in the summer, police officers have carried out more than 4,000 investigations.

Three-quarters of people were found to be fully complying with the need to isolate.

But here's where it gets interesting. More than 200 were found to be ignoring the quarantine requirement and escaped a fine because they listened to the officer on their doorstep. Overall - there were just 38 penalties for breaching holiday quarantine.

But almost 700 other cases were unresolved because police couldn't get to the bottom of whether someone had broken the law - either they were not at home, or nobody of the name under investigation was there. That raises the possibility that people have been putting bogus names and addresses into the system to avoid being tracked down.

On Wednesday, Martin Hewitt, the head of the National Police Chiefs Council, said there would be no "manhunt" for travel quarantine breakers. Quite simply, with crime approaching pre-lockdown levels, frontline officers have more urgent things to do.

But if sticking to such rules is crucial in driving down infection in the UK, how can these dissenters be convinced not to break them?

'Don't Kill Granny'

Differing, sometimes contradictory, messages and policies across the UK, make it difficult, says Dr Gavin Morgan. A psychologist at University College London and member of "SPI-B", the expert group advising the government on how people will behave during the pandemic, he says having fours sets of rules - for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland - has made it harder to sell the restrictions to all sections of society.

"Where the government is perhaps falling short is around making things meaningful and credible," says Mr Morgan. "In order for things to be effective, people have to be invested in it; they have to want to do it."

He argues the Dominic Cummings affair, when the prime minister's chief adviser was accused in the spring of flouting the lockdown, convinced some people the restrictions didn't really matter.

Whitehall's communications teams also need to come up with targeted messages that make sense to specific groups. The closest anyone has come, he says, is when Health Secretary Matt Hancock said to young people, "Don't Kill Granny".

He urges officials to look at societies that are more closely knit.

"If we can begin to generate a sense of community and this feeling of social cohesion, which some countries do really well, our ability to fight Covid will be far more effective."

None of which would guarantee someone won't find inventive ways around the rules anyway.

One student in Brighton told the BBC how she had been furious with her own family, who'd broken the quarantine of a relative. The relative had been isolating for a fortnight after she'd returned from Jamaica.

"Everyone decided to go visit her instead," she says. "She was following the rules, but everyone else just didn't care. I've ticked off my relatives - but they haven't really listened. They say they care, but they don't really because it hasn't happened to any of them yet. They just think it won't."

Back in her sunny garden in Surrey, Alice, too, didn't think it would happen to her.

"It probably was really selfish of me, and I probably won't do it again," she says, sheepishly. "But at the time, I guess you just think of yourself and you want that holiday - but then you don't want to quarantine. No one wants to quarantine.

"And I don't regret it."

- SOCIAL DISTANCING: How have rules on meeting friends changed?

- TESTING: How do I get a virus test?

- SYMPTOMS: What are they and how to guard against them?

- HOLIDAYS: Where can I go away in the UK?