Coronavirus: The parents in lockdown with violent children

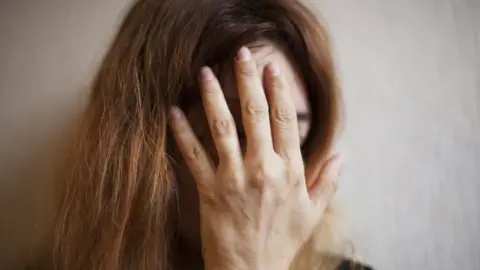

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor some parents, being at home with their children means facing threats, abuse and violent outbursts. How can they cope in the isolation of lockdown?

Julie found out you could buy large knives on the internet when she witnessed her son brandishing one and slashing the furniture at home.

In the past couple of months, she says she has had to call the police twice to their home, most recently as she was barricaded in the bathroom while her son - a young adult - tried to break down the door with a knife. Now the family are living in lockdown together, struggling with isolation, a loss of their support network and a claustrophobic atmosphere that Julie describes as a "tinderbox".

She says she believes her son when he told police that he never meant to hurt her, that he just wanted her to know how angry he was. But incidents of intimidation happen two or three times a week, she says.

Liam suffered trauma as a child and has learning difficulties which affect memory, emotional regulation and social skills. The family manage his aggressive outbursts with the help of a list of friends and supporters who come round at a moment's notice to help defuse tensions. But these coping techniques are threatened by the social distancing rules.

Her husband has to work outside the home, so Julie says if she cannot call on these supporters, "I am very much on my own".

It's not known precisely how many parents live with violence from their children. Figures compiled by the BBC last year suggest the number of incidents recorded by police doubled to 14,133 between 2015 and 2018 - but many may go unreported.

'Like living with nitroglycerine'

Helen Bonnick, a former social worker and campaigner on the issue, says that international evidence suggests about one in 10 parents may experience some violence from their children, although severe incidents are more rare. Some aggressive children have problems dealing with their emotions, she says, but others are "much more manipulative and controlling, in a way that feels more like adult violence".

Lockdown raises the stakes for these families, reinforcing their isolation and underlining the message to parents from violent children "that they can't go out, that they're stuck in here with them, that they can do what they want and no one will know," says Ms Bonnick.

"Parents who have experienced intimate partner violence and then child-to-parent violence will often say this feels worse - because it's your own flesh and blood," she says.

Neil, who lives in the east of England, says the aggression from his son, Ben, was just "cute" aged four and became worrying when he was eight. Now he is living with a teenager and "suddenly it's quite dangerous" - with Ben increasingly reaching for knives or bottles. Ben is autistic and has moderate learning difficulties as well as ADHD. The disruption to his routine caused by the coronavirus outbreak has sent his stress levels soaring and made angry outbursts more likely, his father says.

"He's that much closer to boiling over constantly. It really doesn't take much for him to turn around and explode. It's like living with a bucket of nitroglycerine sometimes," says Neil.

A key coping strategy before the lockdown was taking Ben for long drives, which he found calming. Now even that has become loaded with anxiety, as they fear being stopped by the police for making an unnecessary journey.

"Life was hard already and Covid is making it harder," Neil says.

Peter Jakob, a clinical psychologist who helps people facing this issue, says the isolation and shame that parents already feel is a major challenge in tackling violence from their children. But he says it can still be addressed, even in lockdown. Dr Jakob encourages parents to have a network of supporters who can launch what he calls a "campaign of concern" - where after an incident, a number of people contact the child using messaging or video-chatting apps like WhatsApp or FaceTime.

"Most children don't want others in the community to know that they act in violent, aggressive or otherwise destructive ways," he says.

If they can no longer "silence their parents" from telling others about their behaviour, they often feel forced to change, he says.

'Being visible is important'

But Suzanne Jacob, chief executive of domestic abuse charity Safelives, says that parents in these circumstances need understanding from the authorities as well as from their communities. She says in some cases children have used police enforcement of the lockdown against their parents, knowing the adults will be blamed if they flout the law.

"So while parents are already feeling blamed and inadequate and guilty, this situation is reiterating how little support is available to them and how much people will misunderstand the situation they're in," she says.

Ms Jacob says she wants to see more acknowledgement from government that home isn't a safe place for some people, whether that's victims of abusive partners or parents with violent children.

"Just acknowledging it is helpful to people. Survivors often say being acknowledged, being visible is really important - it validates that fact that this is a thing that goes on," she says. "Those messages would help people feel like they're not going mad."

* Names of family members and some identifying details have been changed to protect their identities. For more information on organisations that can help if you are experiencing domestic abuse, visit BBC Action Line. Helen Bonnick's own website is holesinthewall.co.uk