Drink spiking: Do men know enough?

facebook

facebookMany of the victims of serial rapist Reynhard Sinaga did not even know they had been assaulted.

After luring men outside Manchester clubs, the post-graduate student would take them back to his flat and ply them with spiked drinks to knock them unconscious.

Although the drugging took place in a very particular set of circumstances, his conviction raises questions about the broader problem of drink spiking.

About three-quarters of victims are women, but men are at risk too.

How much do men know about the risks of drink spiking?

Jared Dolby, a 28-year-old philosophy student in Manchester, says much more practical information is needed about the dangers.

"I'm a more mature student and I'm from a small seaside town and I feel streetwise, but for some of these students coming from more privileged backgrounds, Manchester can be a dangerous city.

"There could be more signposting to the help and advice available. Maybe it's a wider cultural issue. There's a taboo around attacks on men.

"You would hope after such an awful thing [the Sinaga case], people would feel more willing to come forward and talk about these issues."

James King, 25, a student who grew up in Manchester, says a lot of it comes down to "toxic masculinity".

"Men don't feel comfortable in their vulnerability. We probably have a lot to learn from women here.

"Women are expected to be able to ask for help, but rape is not something men are expected to have to deal with.

"Practically, maybe staff at bars and nightclubs need to be aware of the issues too. Bouncers are happy to kick people out, but perhaps they need to be more like guardian figures."

Lloyd Brinkworth, a 24-year-old mechanical engineering student, originally from Worcester, says Manchester University, where a number of Sinaga's victims came from, has emailed male students specifically, pointing them to the services available.

"So there is support out there. Outside the university? I'm not so sure."

Fellow student Liam Ashton, 22, added: "We're a tight-knit group of friends and if we are out then we would always make sure everybody's OK and the girls get home safe.

"But it's interesting that the uni has been targeting young men [with advice].

"It's not something we really think about. Would you know where to go? And would you even want to talk about it?"

What can be done to raise awareness?

Elaine Hindal, chief executive of alcohol education charity Drinkaware, says men face a "pervasive" peer pressure when it comes to drinking, which can make them less aware of their vulnerability when they are out in bars and clubs than women might be.

The charity often hears that people don't report a drink being spiked because they fear they won't be believed, or that they will be seen as "making an excuse" for having drunk too much.

Ms Hindal says this may be "even more challenging for men" because there is not enough discussion around their vulnerability more broadly.

She stresses that the vast majority of drink-spiking victims are women, but that the Sinaga case has brought the issue of male victims to light.

"The kind of advice we give to women applies to them as well - stick together, look out for each other, make a plan to get home together so that you stay safe," she says.

Catherine Bewley, from the LGBT+ anti-violence organisation, Galop, said all victims deserved respect and appropriate support, which did not judge or blame them, whatever their gender or circumstances.

Manchester University students' union says it runs regular drink-spiking awareness campaigns at its venues, in particular during freshers' week.

What can you do to keep yourself safe?

Sinaga is thought to have used the Class C drug GHB - which is used recreationally but can be fatal at a slightly higher dose than he gave his victims - but predators can also spike drinks with other illicit drugs such as ketamine or Rohypnol.

It's near impossible to tell whether a drink's been spiked by the taste or smell, although GHB may taste slightly salty or smell unusual.

The NHS offers some steps that might help to stop it happening:

- Don't leave drinks unattended and keep an eye on your friends' drinks

- Don't accept drinks from people you don't know

- Avoid punchbowls and stick to bottled drinks

- If you think your drink's been spiked or start to feel strange or more drunk than you should be, leave your drink and tell a trusted friend straight away

- Tell someone at home or elsewhere where you're going and when you expect to be home - and have plans for getting home

Some bars provide drinks' lids or plastic stopper devices which can reduce the risk of drink-spiking. Others offer drink-testing kits but they won't test for every drug and don't always work.

How big a problem is it?

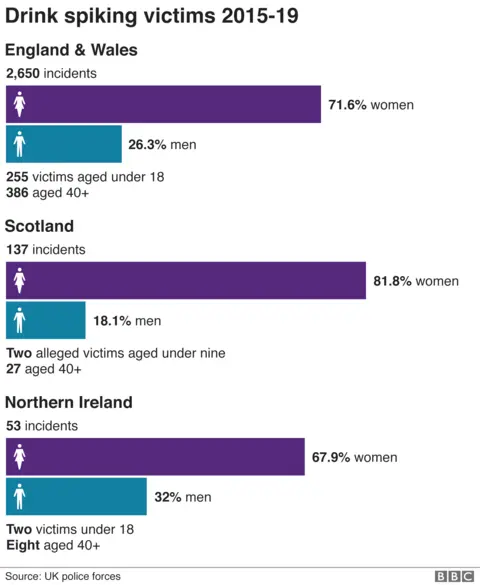

While it's hard to know the true extent as incidents often go unreported, research by the BBC Radio 5 Live Investigations Unit carried out last year found there were at least 2,650 reports of drink spiking in England and Wales between 2015 and 2019.

The data from 22 out of 43 police forces and the British Transport Police showed about one in four of the victims were men.

Between January and September 2019, 68 cases had already been recorded, suggesting the total figure for 2019 was set to hit a five-year high.