Why I spend my weekends ringing birds

BBC

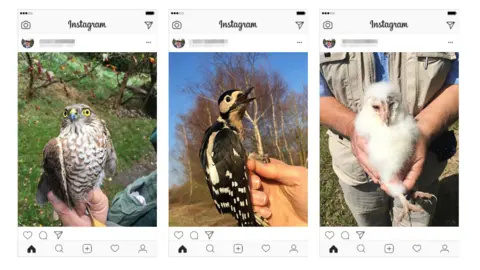

BBCThere is nothing quite like holding wild birds. Their beauty, colours and behaviour never fail to astonish: The blue tit, so common in the UK, turns out to be the most aggressive, pecky little bird imaginable; the goldcrest - the weight of a 20p coin (or a nickel for transatlantic readers) - so tiny; the sparrowhawk, quite a rarity to trap, with its murderous look and talons.

The chance of getting this close to wildlife was one of the factors that attracted me to the surprising and challenging world of bird ringing.

Long before dawn this winter morning, small groups of people all around Britain will wake up to spend several hours in the cold, in marshes, on beaches and sea cliffs. Their goal? To trap birds of as many species as possible in high nets, to measure them, age them, place a lightweight ring with a unique serial number on their right leg and release them, as part of a huge citizen science project which has lasted more than a century now.

BBC

BBC

Joining this project as a trainee, which I did a little more than a year ago, was a startling and rather humbling experience. It remains so. I've been a birder (not a twitcher, please) for many years, and thought I knew a fair bit about birds, at least in the British context. I could identify many dozens of different species by sight and by their song, even if there are always plenty of people in the bird hides who know more than me.

Actually I knew very little. The migration of birds to and from northern Europe from Africa, yes. The details of that migration, when, how they prepare for these extraordinary journeys, their numbers, how high they fly, no.

What was also a surprise to me was that hundreds of thousands of birds actually migrate to Britain in the winter - not just the geese that descend on Norfolk and other wetlands in such large numbers from even colder places such as Scandinavia, Iceland and Russia, but more everyday birds like robins and blackbirds.

We regard them as British birds, but actually their numbers swell considerably in the winter as their continental cousins come in from elsewhere in northern Europe. The reason why robins sing so much in the winter is because they're defending their territory from "outsiders".

BBC

BBC

The ringing scheme is intended to establish how these and other migration patterns are working, which birds are on the decline and on the rise. Retrapped birds provide important clues to the health of bird populations.

The serial number on their rings is matched to the last time the bird was caught, yielding information about how their weight, wing size, fat and muscle depth has changed.

More than a million birds caught every year

The age and sex of the bird in many cases can be gauged by their plumage (debates on tell-tale but minute graduations in colour take up a fair part of our mornings). So the data gathered by 3,000 volunteer ringers, from more than a million birds trapped in the UK and Ireland every year, plays a key role in conservation efforts.

For example, as a result of research done using ringing data, agri-environmental schemes were developed to provide winter seed for farmland birds, which are believed to have contributed to the partial population recovery of reed buntings, a bird that we often trap at our site in Surrey.

Another recent study at Grafham Water north-east of London gave valuable information about nightingales' movements which helped plan management of the habitat at that Site of Special Scientific Interest.

BBC

BBC

BBC

BBC

BBC

BBC

When I say it's an early start, I don't exaggerate. In winter our ringing group arrives at the bird reserve two hours before sunrise, to put up the 10ft (3m) high mist nets. Some reserves have fixed nets that can be unfurled very easily. Ours are erected afresh each time (head torches indispensable here) because we move them depending on the season - no point putting a lot of nets up in the reed beds when the reed warblers are away until late April in sub-Saharan Africa.

Outside the breeding season we play sound recordings of the birds that we're particularly keen to trap - if there's a sighting of bramblings, then that goes on the player. And it makes a difference. The numbers of redwings we trapped went up considerably when we started playing a tape made in Latvia, one of the countries they migrate from during the winter.

Jim Todd

Jim ToddIt would be wrong, however, to explain the motivation of bird ringing as purely a dispassionate collection of data. As my trainer David Ross explains, it's also a matter of curiosity. He says one of the main motivations is watching the migration unfold, from his vantage point at the bird reserve, 25 miles south-west of London.

"Migration fascinates me, especially during the summer when we're ringing reed warblers from Africa. They come back and get caught in almost exactly the same spot they've been trapped in previous years, which is about half the size of a tennis court. I find it incredible they can go to tropical Africa in winter, and find their way back here in the springtime."

BBC

BBC

Under the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981, it is illegal to capture a wild bird, to use a net to do so, or to disturb a bird on its nest. But for conservation purposes, certain agencies are allowed to issue permits to do so, and it is under the British Trust for Ornithology's scheme that I am granted a trainee licence and can do so.

The training is rigorous, under the close supervision of an experienced ringer, and lasts around two years. Mistakes are easy to make - how many birds have I released too early through not holding them firmly enough; or mis-identified, or got their age and sex wrong, or cack-handedly put the ring on wrong. Bird extraction from the mist nets is a skill I have found very hard to learn.

BBC

BBC

The group that I train with varies in size week by week, from three up to as many as seven. My fellow trainees are mostly ecologists or already have a professional link with conservation. We operate under the gimlet eye of trainer David Ross, a former London cab driver with an almost preternatural ability to see how a badly tangled bird can be extracted from the net.

Personal and professional motivation

My fellow trainees' enthusiasm and knowledge of the countryside is inspiring.

Paul Perrins, who works as an ecologist with a development company, has a dual motive for the early mornings. A ringing licence will be a boost for his professional skillset, like his qualification in the trapping and handling of dormice for wildlife surveys. But it's also about conservation:

"While work does offer it to an extent, it's more indirect. But to be able to come out here and know that I'm contributing to a long-term, growing dataset is very rewarding."

BBC

BBCKathryn Dunnett, who works in conservation, agrees that a ringing licence will be helpful in her career, but says there's a more personal reason, the "excitement and thrill when you go to the nets and see what we might have trapped".

But she admits to some reservations: "Is it for me or for the birds? When you catch 100 blue tits, I ask myself, do we really need this data - what are we really learning?"

The answer to that, according to the BTO, is that the vast data sets collected on common birds such as the blue tit can be used to understand what's happening to scarcer species.

The youngest of the trainees is Alex Bayley, who hopes to have a career in wildlife and conservation. "There is a great privilege in being able to view at such close range and hold wild birds," says the 17-year-old.

"Also, at times like these when global warming and human interference on the natural world is so great, ringing provides data and evidence to support conservation initiatives that have the potential to hugely benefit birds under threat."

BBC

BBC

Photographs: Emma Lynch/BBC