Porton Down: What's inside the UK's top-secret laboratory?

Inside Porton Down, the UK's top secret laboratory, scientists carry out research into chemical weapons and deadly diseases. BBC security correspondent Frank Gardner was given rare access to the highly secretive facility.

Pulling on thick, protective gloves several times a day comes with unique problems, says Rory, one of the youngest scientists currently working at Porton Down.

"The one thing which I've found is definitely moisturiser comes in handy," he says.

"My desk is covered in different types of it."

Ebola, plague, anthrax

Rory works at the Ministry of Defence's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL), better known as Porton Down.

Based five miles (8km) outside Salisbury, in Wiltshire, it is highly secretive, under armed guard and is very hard to get into.

And for good reason.

The laboratories are where some of the country's top scientists carry out research into the world's most dangerous pathogens - diseases that can kill us.

Ebola, plague and anthrax are among the life-threatening diseases under study at this secluded base.

It's also where scientists analysed samples confirming that a Novichok nerve agent had been used to poison former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter.

So what actually goes on inside Porton Down and why does it even exist?

First off, officials there are adamant about what it does not do.

Britain ended its offensive chemical and biological weapons programmes in the 1950s.

The UK has ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention, which obliges all 192 members to destroy their chemical weapons stockpiles.

But Porton Down does produce small amounts for research.

"To help develop effective medical counter-measures and to test systems", it says, "we produce very small quantities of chemical and biological agents.

"They are stored securely and disposed of safely when they are no longer required".

The spectre of chemical weapons has never gone away.

Chlorine, Sarin and mustard gases have all been used in Syria's civil war.

Novichok was deployed in Salisbury in 2018.

At Kuala Lumpur airport in 2017, a targeted assassination was carried out - allegedly by North Korea - using droplets of deadly VX nerve gas.

While those incidents were all deliberate, man-made attacks, there is also an ongoing threat from naturally occurring pathogens.

The 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa killed more than 11,000 people, while a recent outbreak in eastern Congo has killed more than 1,200.

So Britain needs to keep its counter-measures right up-to-date, not just for its armed forces, but also for its general population.

The chemists, micro-biologists, cyber-warfare experts and others who work at Porton Down are, in a way, in the front line of defence against some truly horrific pathogens.

Right at the epicentre of this research is the high-containment facility, a futuristic, two-storey building.

After months of requesting, I was given exclusive, escorted access inside.

Once through the doors, I found it resembled a hospital, with its blank, featureless corridors and pervasive smell of cleaning products.

There are four categories of laboratory, rated in ascending order of virulence or lethality, from non-hazardous to fatal pathogens.

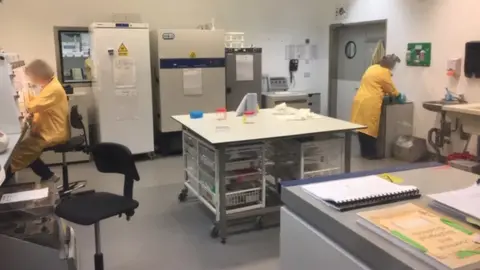

Inside the laboratories men and women, dressed in varying degrees of protective clothing, study a range of potential biological warfare agents.

On the day we visited, we watched from the safety of behind a glass screen as they worked with Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes plague.

The aim of this ongoing research, DSTL says, is "to identify ways to prevent, reduce and treat infection from these hazardous pathogens", and also to "test and develop ways to effectively decontaminate exposed areas, personnel and equipment".

Which brings up the controversial issue of animal testing.

During my visit I was only shown live larvae in petri dishes, but DSTL maintains that "safe and effective protective measures for the UK and its Armed Forces could not, currently, be achieved without the use of animals".

It points out that several of the products and procedures developed by them are now in use by the NHS.

"DSTL is committed to reducing the number of animal experiments", it says.

"DSTL Porton Down currently uses less than half of 1% of the total number of animals used in experimentation in Great Britain. All research involving animals is licensed by the Home Office."

Porton man

Everyone who works in this facility has to be security cleared or "developed vetted" - their personal backgrounds investigated and cleared to make sure they don't present a security risk.

Russia is known to be interested in what goes on behind the chain-link fences and beyond the armed patrols - and not just because of the Novichok case.

For years, proscribed terrorist organisations like al-Qaeda and Islamic State have also shown a disturbing interest in both chemical and biological weapons research.

Which is partly why DSTL carries out extensive testing of the latest defences against poison gas.

In a separate building on the same estate, we are shown something called "Porton Man".

It's a life-size mannequin - a robot - designed to walk and run in the same way a soldier would in a combat zone.

It's wearing a black respirator and chemical protective camouflage. Underneath there are detectors attached to the mannequin's body.

During a live test - which we were not shown - the room is sealed and sulphur mustard gas pumped in and circulated with giant fans.

Do the sensors ever detect any leaks in the suit, I ask?

The answer is equivocal.

"If you want 100% protection against chemical agents", I was told, "then you need a gas-tight suit and self-contained breathing apparatus".

Since this would not be practical in field conditions, a balance has to be found between protection on the one hand and impossible physical restrictions on the other.

So the aim of Porton Man, a facility which the US Government also uses, is to make sure that the seams and seals on the suit provide what DSTL terms "the necessary level of protection".

Given world events, we probably haven't heard the last of Porton Down.

Whether it's Novichok nerve gas, bubonic plague or microbial-resistant bugs, this secretive Wiltshire base is likely to remain Britain's frontline defence against them for the foreseeable future.