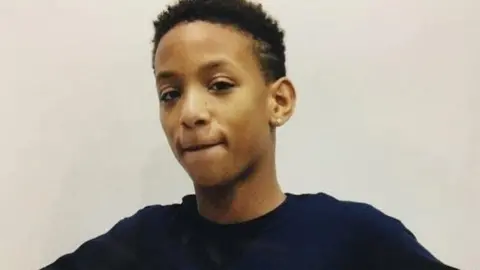

Corey Junior Davis: The gang grooming that killed a 14-year-old

The mother of a 14-year-old boy shot dead in gang violence in London has said a report into the scale of the problem confirms everything she experienced with her own son.

Corey Junior Davis, known as CJ, died in September 2017 after an apparent gang-related drive-by shooting in East London. Police are still hunting his killers.

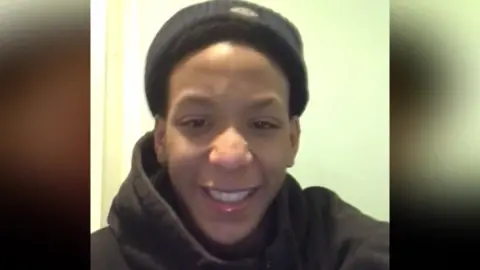

A serious case review later found that he and his mother Keisha McLeod were failed by local agencies that could have protected him from a gang life.

The Children's Commissioner for England has said that local authorities are not grasping the scale of the gang problem as they have very little idea which vulnerable youngsters are being groomed and targeted into a life of crime.

"The report confirms everything that I believe - and was confirmed in the serious case review [into my son's death]," said Ms McLeod.

"CJ was part of the [thousands], he was in the clutches of youth violence and I was letting the authorities know what was going on - but nothing was done."

Ms McLeod says her son was bubbly and loving - but as he entered his teenage years and secondary school he became increasingly troubled. Diagnosed with ADHD and receiving medical support to manage the condition, he struggled to settle into a new school.

Keisha McLeod

Keisha McLeodBy January 2016, aged 13, he was excluded because the school concluded he couldn't manage his behaviour. He was moved to a pupil referral unit - but within months, police were receiving intelligence that he was associating with a drugs gang.

It was a clear warning sign that he was being groomed as a recruit - and CJ even told his mum what was going on.

"When he was going to the pupil referral unit, there were different types of kids there that he was mingling with - and they would walk to the shop, go to the bus stop, go and get chicken and chips - but there would be other people there buying the chicken and chips."

The people offering to feed him were the gang members seeking to win his trust. And once CJ's trust was won with small acts of generosity, he was then asked to temporarily hold packages - meaning drugs that the pushers did not want to carry themselves.

Keisha McLeod

Keisha McLeodWhat happened next was the start of a long list of failings. Despite intelligence from the police and warnings from his family that something was going wrong, CJ's future was not discussed at a child protection conference within the London Borough of Newham, where he then lived.

Instead, his file was sent to the local Youth Offending Team. In other words, says Ms McLeod, her son was treated as a criminal, rather than a victim in the making.

And all the time, he was becoming more and more scared. By the summer he had bought himself a "Rambo" style knife and a bulletproof vest to protect himself.

In November 2016 he disappeared for a week - and refused to tell the police on his return what he had been doing. His behaviour now had all the hallmarks of a child who had fallen under the control of a gang - a child who was being tasked by older, violence-hardened criminals to sell drugs on their behalf.

The full facts became clear to Ms McLeod the following month.

"He called me one evening when he was supposed to be going to a youth centre," she recalls. "He was very agitated and said 'Boys want me to sell drugs until nine'.

"I found him and he had a fair amount of crack and heroin with him, which I took off him. I took him home and I hugged him. I was so grateful that he had contacted me in that moment because it could have gone in so many different ways."

Ms McLeod, horrified, disposed of an estimated £600 of drugs. CJ now believed his life was in danger from dealers to whom he owed a debt. His mother knew she had to find an escape route for her son before it was too late.

Read more on youth and gang violence:

She spoke to social services, the police and the housing authorities in Newham where she was then living.

"Anyone who had anything to do with him was aware of what had happened," she says. "

Newham's social services team now had clear evidence CJ was being groomed to be a drugs dealer. The Metropolitan Police added him to its controversial "gangs matrix" - a database of known or suspected members who are targets for investigation.

Keisha McLeod

Keisha McLeodWhat did other agencies do?

"When it came to help, there was not much help," she says. "I was scared for him and he was scared for himself. It was just me and him left to sort this out. The most important one for me was housing, to get us out of the area. To be out of the clutches of the gangs so he could continue being a child. And I felt that I was the only one who was doing my duty."

Her urgent pleas for help in moving never happened.

In January 2017 - a year after everything had begun to go so badly wrong - Keisha McLeod tried to protect CJ by moving him to her brother's home in south London.

But now that CJ was in another London borough, he ceased to be Newham's case. Its social services officials didn't tell their counterparts in Lewisham. Nobody with the power to help his family was now offering to do so.

CJ was indebted to the older men in the gang and was travelling backwards and forwards across London doing their bidding. He was arrested in April 2017 and convicted of carrying a knife. He told police he was carrying the blade because he was being threatened on social media.

By the summer, in what was the last throw of the dice by his family, CJ was back in Newham - now living with his grandfather. On his return to the borough, his rating on the gangs matrix was raised from "green" to "amber" - meaning detectives believed he was an increasing threat to the community.

But, says Keisha McLeod, the threat was from others. And the victim was CJ himself.

Keisha McLeod

Keisha McLeodOn 4 September 2017, her son was in a group of young people when a stolen Range Rover drove past. An occupant fired multiple shots - and CJ was fatally injured with a bullet wound to his head. He died in hospital the next day, surrounded by his family.

The police investigation into his killing continues.

The Serious Case Review into CJ's death is a stark document. In its neutral language it describes how agencies failed to protect a vulnerable teenage boy.

"Despite hundreds of professional hours provided by a multitude of people, discussion at dozens of meetings over several years and provision of multiple forms of support (albeit with limited intervention), little changed for [CJ] and risk was not effectively managed," it concludes.

Keisha McLeod puts it more simply.

"I was saying, 'Please help', and nothing occurred," she says. "I one hundred percent believe I was let down. He's not here. That says it all."