Reality Check: Why did child screen advice not go further?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNew guidance on screen use for under-18s has stopped short of telling parents how long their children should spend on the devices. Some studies have linked higher screen use to obesity and mental health problems, so why do the recommendations not go further?

Many of us will have seen the stories warning about the health problems linked to excessive screen use, or worried about how we or our children use our phones, computers and televisions.

So the fact that new guidance drawn up by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) steers clear of spelling out whether there should be limits on time spent in front of screens may come as a surprise to some parents and teachers.

Last January, head teachers union the Association of School and College Leaders surveyed 460 secondary school head teachers in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and found 96% had received reports of pupils missing out on sleep as a result of social media use, with most feeling the students' mental health and wellbeing had suffered as a result.

What does the guidance say?

The guidance, the first of its kind in the UK for children, says it is important that screen use does not get in the way of healthy habits like sleep, exercising and time with family.

It recommends one clear rule on limiting screen use: devices should not be used in the hour before bed, because of the growing evidence that they can harm sleep.

But beyond that, it offers no hard answers, instead encouraging parents to consider a series of questions to determine if there might be a problem with screen use in the family.

These include checking if screen time is under control, whether it interferes with family time or getting enough sleep, and whether snacking gets out of control while using the devices.

It recommends that families "negotiate" screen time limits with their children based on their needs.

What evidence did they consider?

The guidance was largely based on a review of the existing body of scientific evidence that was co-authored by the college's president Prof Russell Viner.

This looked at 940 journal summaries and incorporated 13 previous reviews on screen use and children and young people's health, covering everything from mental health to food consumption and sleep.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLooking across the existing research, experts found "moderately strong" evidence for associations between screen time and greater obesity and higher depressive symptoms.

There was moderate evidence for an association between screen time and higher calorie intake, a less healthy diet and poorer quality of life.

The review concludes that the data "broadly supports" policy action to limit screen use by children and young people.

It also calls for more research into the issue to understand the impact of the contexts and content of screen use on children's wellbeing.

One challenge is that this is still a developing area of science, and experts in the field say many of the studies so far carried out have been of low quality.

Most of the evidence in the review was based on television screen time.

So how much time do children spend looking at screens?

A 2017 study carried out by Ofcom, the broadcasting regulator, found that the traditional TV set is still used by more children than any other device - even though there has been a decline in TV viewing over the last decade.

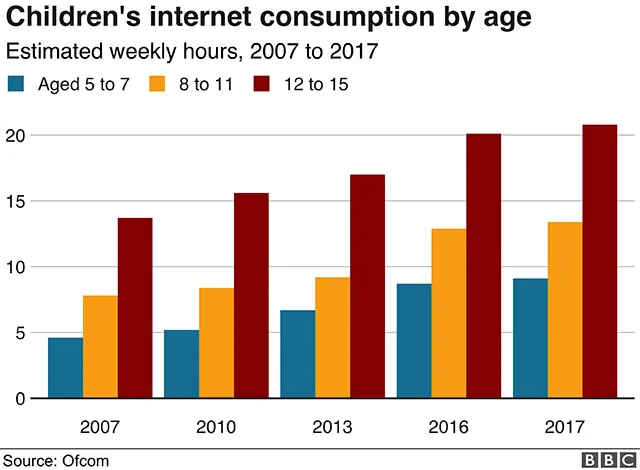

But for older children (12-15 year-olds) the internet is king. This age group spends close to 21 hours a week online.

The growth of YouTube has also shifted the media environment, according to Ofcom.

Half of three to four-year-olds and more than 80% of five to 15-year-olds now use YouTube.

In terms of content, Ofcom says younger children are most likely to use YouTube to watch cartoons, animations, mini-movies or songs, while older children are most likely to watch music videos and funny or prank videos.

So why doesn't the guidance go further?

There are a number of reasons the college has been cautious about setting limits on screen use.

Research, including in this review, has tended to lump all types of screen use together, ranging from browsing social media to playing computer games or viewing TV programmes.

And part of the problem is that studies have shown an association but this does not definitively prove that screen use is causing health problems.

How we use devices may also be more important than how much we use them, they say.

For example, there is likely to be a difference between using a tablet for educational purposes compared to browsing social media, although even here the evidence is not yet clear.

The college also says that attempts to recommend limits on screen use in other countries, including the US and Canada, have failed to change behaviour.

Beyond this, Prof Viner and his colleague, Dr Max Davie, also from the RCPCH, expressed doubts about some of the concerns over screen use, pointing out that devices offer benefits, too.

Prof Viner added: "The genie is out of the bottle - we cannot put it back.

"We need to stick to advising parents to do what they do well, which is to balance the risks and benefits. One size doesn't fit all."