Is another year of rising knife crime ahead?

MPS

MPSSteve Narvaez Jara had just seen in the new year at a party in Islington, north London.

The 20-year-old had everything to look forward to: he was studying physics and aerospace at the University of Hertfordshire and hoped to become a pilot.

But shortly after midnight, the Ecuadorean was murdered - the first of more than 70 victims in London to be fatally stabbed in 2018. Three young men, arrested over the killing, remain under investigation.

On 3 January, 44-year-old Elizabeta Lacatusu was stabbed to death in Ilford by her ex-partner.

Five days later 34-year-old Daniel Frederick was stabbed in an unprovoked attack as he returned to his home in London. Five teenagers were jailed for his killing in October.

These deaths were the start of a terrible year for knife-related violence in England and Wales which has raised questions about policing, public services, gangs, drugs and youth culture.

Getty Images

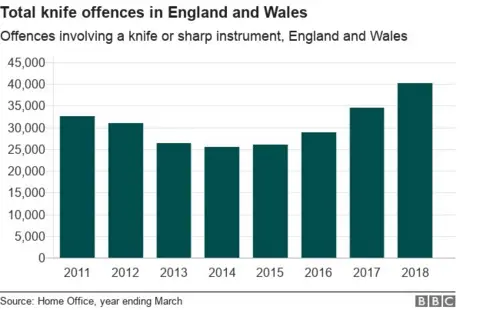

Getty ImagesThe most recent set of figures, from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) - covering the first six months of 2018 as well as the final half of 2017 - show that police recorded 39,332 offences involving a knife or sharp instrument, a 12% rise year-on-year, and the highest number since 2011.

Data from the Greater Manchester force were excluded from those figures because the ONS said they weren't directly comparable.

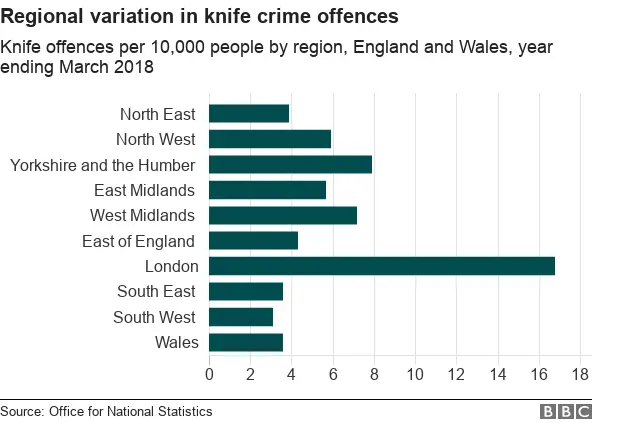

London had by far the highest rate of knife crime, with around 17 offences per 10,000 people, followed by West Yorkshire with 10.7 offences per 10,000 people, and the West Midlands which had 9.8 offences per 10,000 people.

The vast majority of knife crimes were robberies (16,801) or assaults (18,402); 263 were cases of murder or manslaughter, 50 more than the previous year.

The centrepiece of the government's response to the problem was a 112-page Home Office plan published in April 2018, which contained extensive analysis on trends and possible causes of violent crime but was rather short on new and substantive measures to tackle it.

One of the main drivers, it concluded, was the increasing availability and potency of crack cocaine.

It said the growth in the drugs trade was fuelling violent disputes between gangs, particularly those that use young people to distribute and sell supplies to rural and seaside towns - a phenomenon known as "county lines".

To pool intelligence and target those at the helm of the criminal networks, the Home Office provided £3.6m to set up the National County Lines Co-ordination Centre.

Led by the National Crime Agency, the centre only started operating in September, so it's probably too early to judge whether it's having an impact.

Prevention and early intervention were said to be "at the heart" of the government's Serious Violence Strategy which included £11m for projects to divert young people away from trouble.

But less than three weeks after Amber Rudd had unveiled the strategy in April 2018, she resigned as home secretary in the wake of the controversy over the treatment of the Windrush generation of immigrants, and her successor, Sajid Javid, has announced proposals which are likely to go significantly further.

Mr Javid believes there needs to be a "public health" approach to tackling knife crime and other serious violence by ensuring police, schools, local authorities and health care workers abide by a legal duty to take action to prevent it.

Knife crime should be treated like a "disease", he has said.

A consultation on the idea has been promised but has yet to be published, though bids have been invited to run a £200m Youth Endowment Fund, which will allocate money to schemes over 10 years to steer young people away from violence.

In London, plans for a public health approach are a little more advanced. London Mayor Sadiq Khan has set up a Violence Reduction Unit, modelled on one in Scotland where the number of murders has halved in a decade.

Reuters

ReutersThe key to the Scottish initiative is that police and other agencies work together to identify young people who are at risk of being drawn into violence and find them alternatives to gangs and criminality.

The programme also tries to deal with the triggers - domestic violence, social isolation, exclusion and mental health. Mr Khan cautioned that it's a long-term answer - it could take 10 years or even a generation to make "significant progress", he told the BBC.

For law enforcement, the approach in the immediate term has been "suppression": arresting those who are carrying knives and getting weapons off the streets.

If a surge in knife attacks goes unchecked - as has appeared to be the case at various times this year - that can create a climate of fear in which more people go armed, leading to a dangerous cycle of violence.

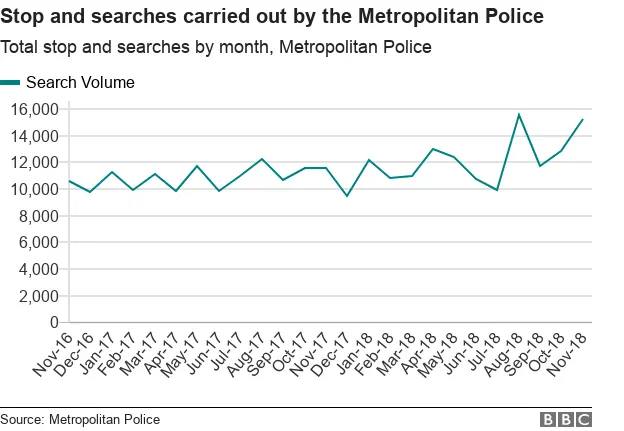

In the past, the principal tactic favoured by police to find weapons and deter violence was stop and search. But its use has plummeted over the past seven years and is now at its lowest level since 2002.

In the 12 months to the end of March, there were 282,248 searches in England and Wales, a fall of 7% compared with the previous year.

More recently there are signs that searches are on the rise again, with the Met carrying out more than 15,000 in November, an increase of almost 4,000 on the year before.

Stop and search is one of the primary tools deployed by the Violent Crime Task Force, a dedicated unit of 272 officers set up by the Met in April to prevent street violence and catch knife offenders.

The aim of the task force is that by a more robust policing response - there have been more than 2,000 arrests so far - the message will get through that knife crime won't go unpunished. That's likely to mean more work for the courts, which are already seeing the largest number of such cases for eight years.

It will be well into 2019 before we know whether that tough approach has helped to halt the spike in knife crime, and stopped the heartbreak suffered by the family of Steve Narvaez Jara from happening to others.