Reality Check: What are the rules on building skyscrapers?

DBOX for Foster + Partners

DBOX for Foster + PartnersA skyscraper measuring more than 300m high is planned for London - one of hundreds in the pipeline. So what are the rules for high-rise buildings?

There's already a Shard, not to mention a Walkie-Talkie, a Cheesegrater and a Gherkin. Much of London's cityscape is filling up with colourfully named and nicknamed high-rise buildings. And the architect Lord Foster has put in planning permission for another.

Known as the Tulip, it would be 305.3m (1,000ft) tall, consisting of a stem structure leading up to a viewing area, rides in transparent pods, a restaurant, a miniature park and an education zone. Just three feet shorter than the Shard, it would become London's - and the UK's - second-highest building.

The City of London's planning department will now look at Foster and Partners' application. The company hopes the building will be finished by 2025.

Visitors to the Tulip, should it be built, are likely to have plenty of other skyscrapers to look at.

In its latest survey, for the year 2017, the discussion group New London Architecture, found 510 buildings of 20 storeys or more were "in the pipeline" in London.

And high-profile projects are planned in other cities including Manchester,Bristol and Norwich.

There's no single definition of what "high-rise" means. In a city with not many tall buildings it could be as low as 10 storeys. In a city where loftier constructions abound, it could be, say, 40 storeys.

As with other planning projects, it is up to councils in England to decide whether to grant permission.

"Major applications are a heavy responsibility," says Troy Healy, planning associate at the Planning Insight consultancy. "They can shape the environment for generations to come. Good town planning acknowledges complexity, and safeguards the future of our community."

Considerations for council planning committees include the impact on public services and transport, and how much the building would block light for people living nearby.

St Michael's

St Michael'sCouncils are asked, but not compelled, to come up with a local development plan, guiding the nature and character of building in their area.

In London, the mayor's office provides extra city-wide guidelines. Among these, it says high-rise buildings should only be considered in areas "whose character would not be affected adversely by the scale, mass or bulk". They should also "relate well" to the character of nearby buildings, contribute to local regeneration, provide public access to upper floors (where appropriate) and offer ground-floor activities which provide "a positive relationship to the surrounding streets".

The buildings should not increase wind turbulence, noise or reflected glare, or interfere with aviation, navigation and telecommunication.

City of London Corporation

City of London CorporationThere are also rules to protect views of monuments and points of interest. For instance, the 224m (734ft) Leadenhall Building in the City of London, nicknamed "the Cheesegrater", had its profile tapered to preserve the sight line of St Paul's Cathedral from the historic Cheshire Cheese pub in Fleet Street.

This sightline guidance helps explain why London, as opposed to New York or Chicago, does not have lots of rectangular high-rise buildings, and why high-rise buildings tend to be in clusters rather than spread across a wider area.

Foster and Partners says the Tulip - its shaft is 14.3m (47ft) wide - will have a "soft bud-like form and minimal building footprint", providing "a cultural and social landmark" to complement the neighbouring Gherkin.

The City of London approved 99% of planning applications in 2017-18, so the odds of success would appear good.

However, the Tulip isn't universally popular. One person has written to the planning committee saying it "reeks of desperation in its straining after ostentatiouseffect", while another correspondent asks whether there is "a competition for the ugliest skyscraper".

But is there any way a council's decision can be overturned?

If he feels a building goes against his plans for London, Mayor Sadiq Khan can "call in" the application. This means he, rather than the council, makes the decision.

He did this last year, backing two high-rise housing schemes in Tottenham and Wealdstone which councils had rejected.

And, across England, at any stage from conception to completion, the communities and local government secretary can also call in a planning decision. But this doesn't happen often, usually in relation only to planning issues of "national significance".

After Manchester City Council approved the £200m St Michael's development, including a 39-storey hotel, campaigners asked the government to investigate the decision. It decided not to.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith urban space limited and housing demand and land costs high, expect more high-rise developments in the next few years.

But the UK's tall buildings "are small compared with those in a lot of American and Chinese cities", says Peter Murray, chairman of the discussion group New London Architecture. "It wasn't that long ago that we would be comparing ours with those in American cities. Now it's moved to the Middle East and the Far East."

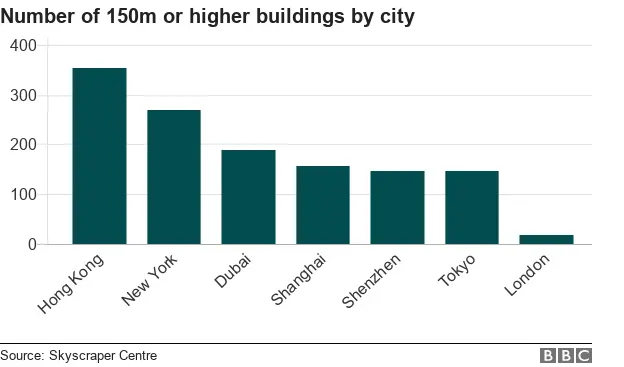

The Skyscraper Centre has put London joint 56th in its global list of cities with completed buildings of more than 150m. With 18, it was equal with Seattle. Top was Hong Kong, with 353, followed by New York, with 269. No other UK city was in the top 180.

Paris has only two buildings higher than 150m, Madrid has five and Berlin has none.

Only three buildings in the world - Dubai's Burj Khalifa, China's Shanghai Tower and Saudi Arabia's Makkah Royal Clock Tower - make it into the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat's 600m "megatall" category.

The Tulip, being just over 300m tall, would creep into the "supertall" category.

The City of London Corporation will decide whether to give it the go-ahead in spring.