Brexit: What does the draft withdrawal agreement reveal?

The draft withdrawal agreement is all about how the UK leaves the European Union. It's not about any permanent future relationship.

It's a long read - 585 pages long - and we've just had a first look at the text. There will be plenty more to say in the days ahead.

But what's in this draft document, that some people thought might never materialise?

Well we've known about a lot of the content for some time.

There are details of the financial settlement (often dubbed the divorce bill) that the two sides agreed some months ago: over time, it means the UK will pay at least £39bn to the EU to cover all its financial obligations.

There's also a long section on citizens' rights after Brexit for EU citizens in the UK and Brits elsewhere in Europe. It maintains their existing residency rights, but big questions remain about a host of issues, including the rights of UK citizens to work across borders elsewhere in the EU.

Transition period

The legal basis for a transition (or implementation) period, beginning after Brexit. It would be 21 months during which the UK would continue to follow all European Union rules (in order to give governments and businesses more time to prepare for long term change).

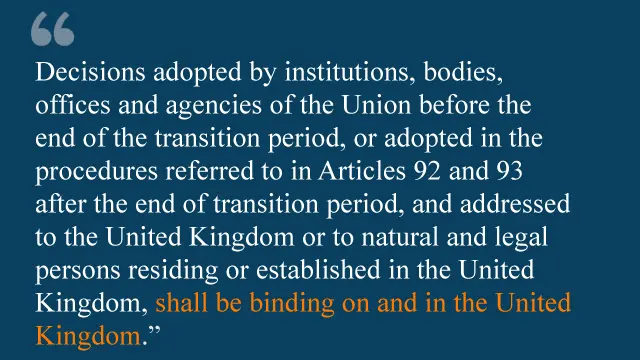

That means that during transition, the UK would remain under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (in fact, the ECJ is mentioned more than 60 times in this document). The document says that decisions adopted by European Union institutions during this period "shall be binding on and in the United Kingdom".

![Notwithstanding Article 126, the Joint Committee may, before 1 July 2020, adopt a single decision extending the transition period up to [31 December 20XX].](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/480/cpsprodpb/8CF4/production/_104348063_extendingtransitionnew-nc.png.webp)

The transition period is also designed to allow time for the UK and the EU to reach a trade deal. The draft agreement says both sides will use their "best endeavours" to ensure that a long term trade deal is in place by the end of 2020. Significantly, if more time is needed, the option of extending the transition appears in the document (although, it makes it clear that the UK would have to pay for it).

The document doesn't say how long the transition could be extended for (in fact they've left the date blank), only that the Joint Committee may take a decision "extending the transition period up to [31 December 20XX]." UK officials hope that the date will be clarified by the time of the proposed EU summit on 25 November.

Northern Ireland

If there was no long term trade agreement and no extension of the transition, that's when the so-called "backstop" would kick in. It's the issue that has dominated negotiations for the last few weeks and months: how to ensure that no hard border (with checks or physical infrastructure) emerges after Brexit between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Both sides agreed back in December 2017 that there should be a guarantee to avoid a hard border under all circumstances. That guarantee came to be known as the backstop, but agreeing a legal text proved very difficult.

So what exactly does this draft agreement say about the border, the backstop and the legal guarantees that underpin it?

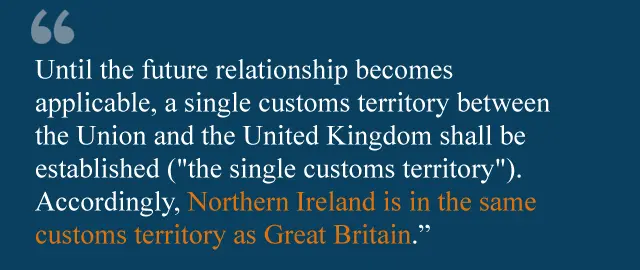

If a backstop is needed, it will - as expected - take the form of a temporary customs union encompassing not just Northern Ireland but the whole of the UK.

The draft agreement describes this as a "single customs territory".

Northern Ireland, though, will be in a deeper customs relationship with the EU than Great Britain, and even more closely tied to the rules of the EU single market.

Fishing

One policy area is excluded from these potential customs arrangements: fishing.

That's because the trade-off between access for UK fish produce to EU markets, and access for EU boats to UK waters, is too controversial. The draft agreement simply states that "the Union and the United Kingdom shall use their best endeavours to conclude and ratify" an agreement "on access to waters and fishing opportunities".

The way out?

There are also details of one of the last issues to be negotiated - the terms on which the UK may be able to leave this temporary customs arrangement in the future.

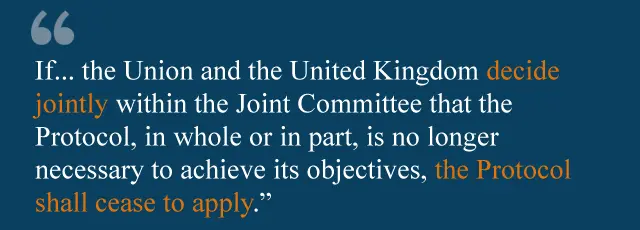

If either party notifies the other that it wants the backstop to come to an end, a joint ministerial committee will meet within six months to consider the details.

But the backstop (which is part of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland) would only cease to apply if "the Union and the United Kingdom decide jointly" that it is no longer necessary. In other words, the UK will not have a unilateral right to bring those arrangements to an end.

For some Brexiteers, that is simply unacceptable.

But, don't forget, other countries will also have their concerns.

They too will focus on the language surrounding a temporary customs union, to ensure that nothing is hidden there which could, in their view, give the UK rights without responsibilities; and - potentially - a competitive advantage.

The EU insists the draft agreement "includes the corresponding level playing field commitments and appropriate enforcement mechanisms to ensure fair competition between the EU27 and the UK."

So, it's not just in London that this document will be closely scrutinised.

Finally one big question: to what extent could these temporary customs arrangements form the basis for a permanent future relationship, which can only be negotiated formally after Brexit has actually happened?