How many people sleep rough in England and how are they counted?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesContained within the pages of the Budget book was a government pledge to publish a consultation early next year to look at bringing in a new tax on foreign property buyers.

When the government first floated this idea in September it said any money raised from the new tax would be used to help people sleeping rough.

Housing Secretary James Brokenshire has vowed to make homelessness "a thing of the past" and said that the government aims to end rough sleeping by 2027.

So how many people are currently sleeping rough in England and how accurate is the data?

The official statistics on rough sleeping are produced once a year by the Ministry of Housing.

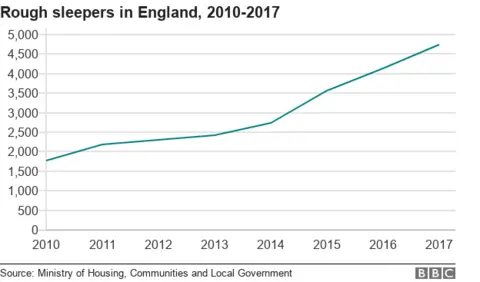

The latest release shows that in autumn 2017, there were 4,751 people sleeping rough in England.

That represents a 15% increase on the year before and more than double the number of rough sleepers in 2010.

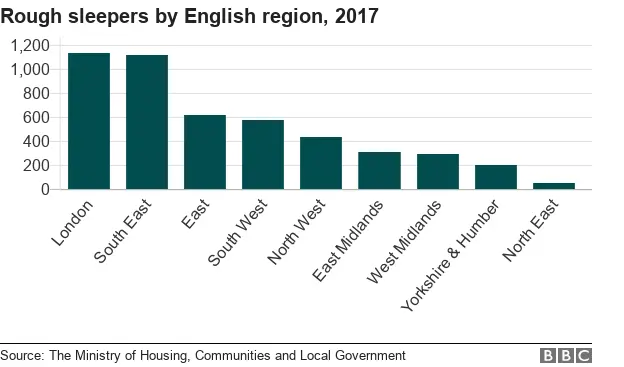

Last year all regions in England recorded an increase in the number of rough sleepers. The biggest, compared with the previous year, was recorded in the North West (+39%).

Overall London had the highest number of rough sleepers (1,137), just ahead of the South East (1,119), which also had the sharpest increase in rough sleeping since 2010, at 261%.

Map built with Carto. Can't see the map? Click here

How is the data gathered?

Local councils collect the data once a year.

Between October and November, councils are required to select one night to carry out either a street count or an estimation of the number of rough sleepers in their area.

If a council chooses to use an estimate it should be based on information gathered from local services, like homelessness charities.

A rough sleeper is defined as someone who sleeps in the open air (such as in the street, in tents and doorways) or in places not designed for habitation (such as in stairwells, car parks and sheds).

The definition does not include people in hostels or shelters.

Getting local councils to carry out the annual count is a useful way of generating consistent data to help understand the national trend in rough sleeping, according to Beatrice Orchard, head of policy at the charity St Mungo's.

However, Ms Orchard also says that because the data only gives a one-night snapshot it "might not give an accurate picture of every single person sleeping rough".

That is because someone who normally sleeps rough won't be counted if they decide to use a shelter on the night the count takes place, for example.

The accuracy of the data also relies on the local knowledge of those carrying out the count. For example, some people may intentionally choose not to sleep on the street because they fear being attacked, says Deborah Garvie from the housing charity Shelter.

"Some people may choose to spend all night on a bus, for example. Women have been known to sleep in people's front gardens because they feel safer," she says.

This adds to the challenge of ensuring that the data gathered is comprehensive.

The Ministry of Housing says the the current system does "provide useful data and is the agreed method for tracking progress in tackling rough sleeping". But the ministry adds that in future it expects local authorities "to develop improved ways of recording and assessing rough sleeping".

Unique number

Another way of monitoring of rough sleepers has been developed by the charity St Mungo's.

It is a comprehensive database on London's rough sleepers, known as Chain (Combined Homelessness and Information Network).

Each individual entered into Chain has a unique number.

"The system allows support workers who go out and identify people to find out why they are sleeping rough. They record all of the contacts on the database," explains Ms Orchard.

In the year ending 1 April 2017, a total of 8,108 people were seen sleeping rough in London by outreach workers - virtually the same as the previous year.

Over half (59%) were seen only once, while only 6% were seen more than 10 times.

However, these numbers cannot be directly compared with the government statistics.

That is because Chain collects information on those seen sleeping rough on the streets at least once over a year - as opposed to the government's one-night snapshot.

The official figures for 2018 should be published in January.