Alexander Perepilichnyy: The questions raised by Russian whistleblower inquest

Family handout/PA Wire

Family handout/PA WireThe inquest of Russian businessman Alexander Perepilichnyy has concluded that he died of natural causes. What were the big questions the coroner was trying to answer? The BBC's Duncan Leatherdale attended the hearings.

Courtroom two at the Old Bailey erupted with laughter, for pharmacologist Robin Ferner had just hit the nail on the head.

"Clarity," he told the 15th and penultimate day of the inquest, "is not something that is manifest in the case."

It was something of an understatement.

Since Alexander Perepilichnyy's death in 2012, questions and speculation have raged.

Was it a natural death? Or was he poisoned because of his status as a whistleblower helping expose a multi-million pound fraud in Russia?

Clarity is what Coroner Nicholas Hilliard QC was seeking,

Who was Alexander Perepilichnyy?

The 44-year-old was a Russian businessman and married father-of-two who had lived in the UK since 2009.

He was a wealthy man, the inquest heard.

Police found details of enormous bank transactions on his computer, the biggest for $500m (£395m) - with connections to farming businesses. His rented house on the high-security St George's Hill estate in Weybridge, Surrey, was worth more than £5m.

He had taken out various life insurance policies worth more than £8m as he sought to buy a new home on the estate. He was also looking to buy a house in Miami.

Alamy

AlamyBut he was also a whistleblower who was helping investment firm Hermitage Capital Funding expose a $230m (£150m) money-laundering scheme in his homeland.

His involvement in exposing the scheme, which had links to big business and organised crime groups, would have made him enemies, Hermitage said.

He was also embroiled with his own legal cases in Russia linked to his alleged debts, a number of which involved a debt-collection firm founded by Dmitry Kovtun, a suspect in the murder of Alexander Litvinenko.

A court in Russia had been told Mr Perepilichnyy "feared for his life" if he returned to his homeland, the coroner heard.

EPA/SERGEI CHIRIKOV

EPA/SERGEI CHIRIKOVBut Mr Perepilichnyy's wife Tatiana Perepilichnaya and brother-in-law both said he had not been threatened, had not fled to the UK for safety, and was not living in fear.

Mrs Perepilichnaya told the inquest speculation about his role as a whistleblower "ruined the reputation of my husband".

"Alexander wasn't politically motivated," she said, adding: "He was very soft, a non-confrontational person."

The Russian also had a Ukrainian girlfriend, Elmira Medynska, who he was with in Paris the day before his death.

There were also suggestions he was working with British secret services but, after reviewing MI5 and MI6 files, the coroner said their reports on Mr Perepilichnyy's alleged involvement would remain secret.

The coroner rejected the possibility secret intelligence could hold clues to the death - saying that, while he had seen sensitive information related to the case, none of it added to the evidence heard in open court.

What happened to him?

At about 17:00 GMT on 10 November 2012, Mr Perepilichnyy collapsed and died while jogging near his home.

Surrey Police quickly determined his death was not suspicious, a view they have not deviated from.

He had been sick the night before after eating in an exclusive Japanese restaurant in Paris.

The inquest heard he had been on a "romantic holiday" with Ms Medynska, a fashion designer he had contacted through a dating website in March 2012.

She told the inquest he also complained of a dish tasting bad and his upper body turned red after vomiting, but he seemed perfectly well again the following morning.

Several experts told the inquest his symptoms matched those of scombroid fish poisoning which could be caused by eating gone-off fish, possibly tuna or mackerel.

Elmira Medynska/Instagram

Elmira Medynska/InstagramHe returned to his home on 10 November and ate a bowl of sorrel soup made for him by his wife.

Hours later he was dead.

The inquest heard he had been doing a lot more exercise in a bid to get healthier and had shed some 3st (20kg), the inquest heard.

Neighbours found him lying in the street and CPR was attempted.

He was declared dead 46 minutes after the ambulance arrived.

Where did the poison suggestion come from?

Surrey Police have always said the death was not suspicious.

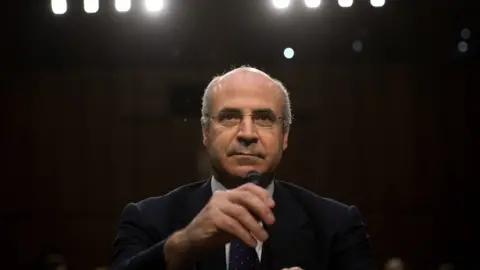

But they were contacted a week after his death by Hermitage, and the firm's CEO Bill Browder, to say he could have been the victim of an assassination based on Mr Perepilichnyy's status as a whistleblower.

"We believe there is a strong possibility that Alexander Perepilichnyy was murdered," Mr Browder told the inquest.

He said there was "state-sanctioned fraud" in Russia and a "continuum of terror" through either threats of violence or legal action.

Mr Browder said the Russian regime "doesn't like to kill people in easy to identify ways", adding: "Poison is one of their methods because they can do it in a plausibly deniable way."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesExperts at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew had identified an "unknown compound" in his system with the same atomic mass as gelsemium elegans, a plant toxin known as "heartbreak grass".

But further examination proved "beyond reasonable doubt" that there was no plant toxin, according to Kew botanist Dr Geoff Kite.

He said finding an unknown compound was not uncommon and the one in question was one of 300 found in Mr Perepilichnyy.

The contents of Mr Perepilichnyy's stomach were not kept for further testing, but consultant pathologist Dr Norman Ratcliffe, who carried out the autopsy, said he saw nothing to cause concern.

Dr Ratcliffe said it was standard procedure to dispose of the contents if all appeared normal, which he said it did in Mr Perepilichnyy's case.

The vomiting the night before his death was most likely to have been caused by the poisoning from bad fish, the coroner was told by several experts.

Cardiologist Dr Peter Wilmshurst said the symptoms - bad tasting dish, vomiting, reddening of the upper body - matched his own when he contracted scombroid fish poisoning from a gone-off tuna steak.

So what killed him?

Two post-mortem examinations failed to find a cause of death.

Dr Ratcliffe said there was no evidence of third-party involvement but he found an anomaly in Mr Perepilichnyy's heart which, in the absence of anything else unusual, "could explain his sudden death".

But he said he would defer to forensic pathologist Dr Ashley Fegan-Earl to establish the cause of death.

Dr Fegan-Earl said in a case of a 44-year-old man with "no circumstantial history to raise concerns", Sudden Adult Death Syndrome would have been the cause.

But, as speculation over poisoning had been raised in Mr Perepilichnyy's case, he added: "The only proper conclusion that can be posited is that the cause of death is unascertained."

No traces of any plant toxin were found, while too much time had passed for certain other poisons, such as cyanide and nerve agents, to be tested for.

They could therefore not be ruled out but their use was "unlikely" according to various toxicology experts, as they would have shown other affects.

Dr Wilmshurst said it was possible the food poisoning in Paris triggered a cardiac arrhythmia which could in turn have caused a fatal heart attack when put under stress by jogging.

Such an event is rare, he said, but, like the National Lottery, "the fact that any one individual has a very low chance of winning doesn't mean no one will win".

What did police do wrong?

Surrey Police have admitted mistakes were made.

In short, they did not treat his death as a potential murder, partly because they had not realised who he was and what his history had been.

PA

PABut having heard all the fresh evidence found throughout the inquest, Det Supt Ian Pollard, who ran the investigation, said he had heard nothing to change his original opinion.

This was not a murder, he said.

Det Supt Pollard was asked why the force did not react with more suspicion immediately after Mr Perepilichnyy's death.

The investigation was compared to that carried out in the case of Mr Litvinenko in 2006, or the poisoning of the Skripals in Salisbury earlier in 2018.

Copyright unknown/Supplied by Rex Features Ltd

Copyright unknown/Supplied by Rex Features LtdMr Pollard said Mr Perepilichnyy was not displaying the symptoms of poisoning as were seen in the other cases.

"It was very clear very early on some agent had been used in those cases," Mr Pollard said.

"We did not see that with Mr Perepilichnyy."

The force was also criticised during the inquest for losing its copy of the contents of Mr Peprilichnyy laptop - and for asking a civilian worker to look through the contents of the computer and make judgements about what should be investigated.