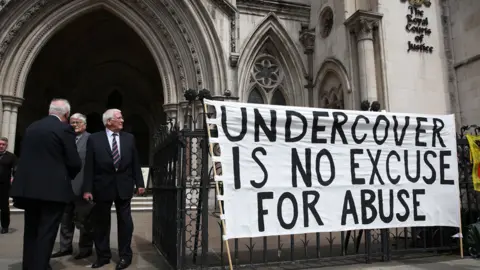

Undercover police inquiry: Can it get to the truth?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is the public inquiry that has cost £9m and got very little to show for it so far.

A month from now, the Undercover Policing Inquiry (UCPI) - one of the most controversial and least understood investigations ever into abuse of power - will be three years old.

It was announced in March 2015 and when its chairman set out its aims, he anticipated there would be a report on the home secretary's desk three years later.

Instead, it is going to be at least another year before the victims of those abuses of power will hear any of the evidence about why they were subjected to surveillance and monitoring, despite admissions from the Metropolitan Police that some of what happened was profoundly wrong.

The UCPI was launched after a series of scandals about policing units dedicated to monitoring political protest.

In short, the allegation is that these units that had developed over 40 years were out of control.

- Officers from the Metropolitan Police's now disbanded Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) tricked women whom they were targeting into sexual relationships.

- Some of them stole the names of dead babies to create a cover story complete with birth records.

- Some of these infiltrations led to proven miscarriages of justice.

- The most toxic allegation that triggered the inquiry was that an officer infiltrated the Stephen Lawrence justice campaign.

Other

OtherBut as that third anniversary approaches, the UCPI is at a crossroads, as a series of stand-offs in preparatory hearings have made clear.

There are now more than 200 "core participants" to the inquiry.

They include a growing list of women who have discovered that a disappeared partner was in fact an undercover officer who had made his fake excuses and left.

Hearings were partly delayed because of a human tragedy - the original chairman, judge Sir Christopher Pitchford, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease and died last October.

Sir John Mitting, his successor and a judge with perhaps unrivalled experience of dealing with secrecy and national security, has faced the unenviable task of trying to push the inquiry forward.

But it is not proving easy.

At the heart of the challenge is what could turn out to be an impossible circle to square - can the public inquiry deliver a report that people have confidence in if a great deal of the evidence and findings will remain secret?

At his first public statement last November, Sir John said all of the women were entitled to "a true account" of how and why they came to be in a relationship with an undercover officer and what police chiefs knew about it.

He also said the women should know the officers' real identities.

This issue came to a head in the inquiry's recent hearings in which it has tried to make headway in deciding which former SDS officers are named.

Each of the approximately 170 officers has a code number.

The officer and Scotland Yard can ask for anonymity - and the inquiry chairman decides.

A similarly complicated process is under way to censor the millions of pages of documents at the heart of the inquiry.

The scale of these two exercises has largely been responsible for the huge delays - but now things are moving with regular rulings from the chairman on who will be named.

UCPI

UCPIThe problem is, say campaigners, that things are not looking good.

Take the case of Officer "HN297", for example, who operated undercover in the SDS between 1974 and 1976 and has since died.

He went undercover in the Troops Out Movement, which campaigned against the British Army's role in Northern Ireland, and a separate revolutionary socialist group called Big Flame.

The Met asked the inquiry to protect his real identity but not his "cover" name.

So we learnt that HN297 used the fake identity "Rick Gibson" - but not who he really was.

Sir John ruled that Gibson's real name was unlikely to add anything and would also interfere with his widow's privacy.

Investigators within the network of political activists who were monitored then established that Gibson had in fact had two intimate relationships.

One of the women, known only as "Mary", has now come forward to demand answers, including Gibson's real name.

The fact that Gibson had these relationships in the 1970s casts great doubt over the the idea that the abusive relationships came much later on and involved just a few men.

If it was happening so long ago, it could have been an infiltration strategy from day one.

The estimated 30 relationships already discovered could balloon as more is learnt about the other SDS officers.

Therefore, the victims say, nobody will know the truth unless they get the names - something that Sir John Mitting is not prepared to do unless there is prior evidence of a relationship.

While he is looking again at the HN297 file, campaigners say the way it has been handled shows how the inquiry could fail.

But there is another major decision facing the inquiry - how much can it reveal about the senior officers who oversaw the Special Demonstration Squad; particularly those involved in the monitoring of the Stephen Lawrence family campaign.

In theory, senior officers will give evidence in person at the inquiry.

But it may not turn out that way because many of them also had undercover careers themselves.

While the inquiry has committed to revealing the cover name used by "HN81" - the officer sent into the Lawrence campaign - it is not currently minded to say anything at all about his boss, currently codenamed "HN58".

His evidence on why the Lawrences were targeted - what the SDS was hoping to achieve by gathering intelligence on the family's justice campaign - will be crucial to the commitment to get to the truth.

But Sir John concluded after hearing arguments behind closed doors that there was a personal risk to HN58 because of what he did during his own undercover deployments.

It is not yet clear whether he will stick to that position in his final ruling, but it is just another example of how difficult the inquiry is turning out to be.