Could more women soldiers make the Army stronger?

MOD

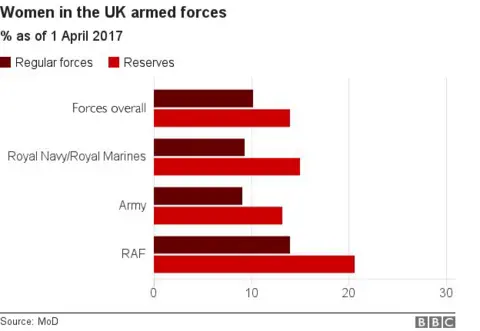

MODOnly one in 10 members of the UK's armed forces is a woman - as is the case with many of its allies. But could it be that more female soldiers would not only ease a recruitment crisis, but also make the forces stronger?

At the height of the war in Afghanistan, coalition forces were at risk of being unable to gather vital information and intelligence from women in the towns and villages where they were operating.

A solution came from female soldiers, who were sent into these communities as engagement teams - talking to local women who were unlikely to speak to their male colleagues.

It was only one example of the benefits that diversity in the armed forces can bring.

Yet the debate around whether women should serve tends to focus on physical strength, or gender equality, rather than whether they could actually make the military more effective.

Earlier this year, the RAF became the first service to open all roles to women, when it extended the right to apply for its ground fighting force - the RAF Regiment.

It will be followed in 2018 by the Navy, when it opens applications for the Royal Marine Commandos to women.

Next year will also see the Army finish opening up all its roles to female recruits, a move which follows the lifting of the ban on women taking part in ground close combat and will bring the UK in line with many of its closest allies.

Only last year, three out of 10 Army positions were closed to women.

It is too early to know just how many more women will be tempted to join the armed forces following these changes.

Before the law was amended, critics said having more female recruits would reduce operational effectiveness.

For example, Colonel Richard Kemp, who led British forces in Afghanistan in 2003, said women would be a "weak link", adding only "a very small number" wanted to join the infantry, with "a fraction" having the physical capability to do so.

Indeed, it is possible that only a small number of women will want to take part in close combat.

Those who do apply will have to meet the same high physical standards as men, with evidence suggesting that women are less likely to pass the tests for strength and aerobic fitness.

Among the physical elite who will get through, there is a greater chance of injury for all recruits to the infantry, particularly in the roles that require weight to be carried for long periods, with the risk highest among women.

These risks are being closely monitored by the MoD as the changes are introduced.

Critics also raised concerns that mixed-gender teams would lack cohesion, but while evidence suggests that forming a unit can be harder, it was also found that these problems can be overcome by training and leadership.

But focusing on strength risks overlooking the skills that women can bring - across many roles - to the armed forces.

Women have operated with distinction on the front lines in recent conflicts in non-combat roles, such as medics and engineers.

They have also worked alongside coalition forces that already allow women to serve in all combat roles, including Canada.

Shutterstock

ShutterstockAttracting more women broadens the range and number of potential recruits to draw from, deepening the pool from which to choose the best recruits - regardless of gender - with the best range of skills.

But the argument is more nuanced than simply needing more women in order to speak to other women.

Having more diverse armed forces reflects the complexities of the conflict zones in which they now operate.

Battles are often fought in highly populated areas, rather than the remote frontlines of the 20th Century.

Soldiers not only have to take on the enemy, but must also build relationships with a wide range of people - men, women and children from many backgrounds.

The armed forces are also often used for more than the fighting of wars - contributing to stabilisation efforts, for example.

Again, this is the type of scenario where having soldiers with many different skills - from conducting combat operations, to working in a diplomatic capacity and providing humanitarian support - makes success more likely.

The enemy has shown that it is readily prepared to use women in conflict, in the most unflinching of ways.

Boko Haram has realised both the propaganda and practical value of using women as suicide bombers.

And, as so-called Islamic State struggles to recruit enough male cadets, they have called on women to take up arms and fight.

Mohamed Madi/BBC

Mohamed Madi/BBCThese changes have been driven by military advantage, rather than by any idea of gender equality.

No combat uniforms

At the moment, however, women make up only 10% of the UK's regular armed forces, a figure which is reflected across many Nato members. They account for 14% of the UK's reserve forces.

Despite a range of approaches being tried to attract more women it seems that the armed forces are still seen as a career for men.

Yet there is a struggle to find sufficient recruits, with figures for the Army showing numbers were 4,000 below target.

Making the armed forces more appealing to women could go a long way towards addressing this shortfall.

This year 30,000 more women than men were expected to start degree courses in the UK.

That's a lot of talent the armed forces will not have access to if those women are not considering a career in the military after they graduate.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut progress is slow and inconsistent.

The Armed Forces (Flexible Working) Bill 2017 that is currently going through Parliament will allow recruits to work part-time, making a career in the armed forces more attractive to those with a family.

Other measures that would seem relatively straightforward are not addressed.

For example, female recruits could be provided with combat uniforms and equipment designed for women rather than men.

This may seem a peripheral issue, but it risks representing the idea that women are an afterthought, rather than an integral part of military operations.

Until more women are present throughout the military - up to the highest levels - the full extent of their impact cannot be known.

The military offers training and opportunities which should appeal to the brightest and best candidates.

But if it is a career that 50% of the population is unlikely to choose, we should perhaps be asking ourselves why?

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Hannah Bryce is the assistant head of the International Security Department at Chatham House. Follow her @hannahekbryce.

Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, describes itself as an independent policy institute helping to build a sustainably secure, prosperous and just world.

Edited by Duncan Walker