Are UK drug consumption rooms likely?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow close is Britain to creating places where all drugs are legal?

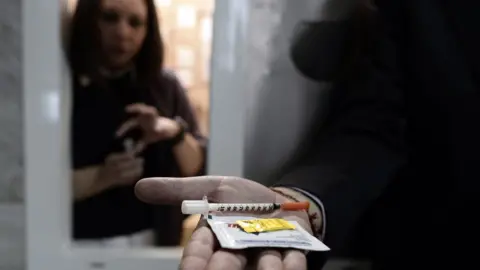

What does the Home Office really think about drug consumption rooms - safe and supervised places where addicts can inject or inhale illicit substances without fear of prosecution?

DCRs, as they are called, are used in other countries to reduce the risk of chronic drug users dying from an overdose or an infection.

But the idea of creating spaces where illicit drugs are effectively decriminalised goes against the government's long and carefully maintained line that illegal drugs are dangerous, and those who possess them should be prosecuted.

This summer, as record drug deaths were reported in the UK, the Home Office had to respond to recommendations from its drug advisors, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), on how to reduce "Opioid Related Deaths in the UK".

Local successes

Among the advisor's suggestions was the idea of opening DCRs in places with a significant street heroin population.

Civil servants looked at their own Home Office research on drug consumption rooms conducted in 2014.

It had concluded there was "some evidence for the effectiveness of drug consumption rooms in addressing the problems of public nuisance associated with open drug scenes, and in reducing health risks for drug users".

The research added that while DCRs in other countries had been controversial and legally problematic, locally-led schemes "have been most successful".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn short, the Home Office's own evidence showed that if you want to cut drug deaths, local DCRs can help. So what should minister's say to the advisory council?

Well, this was the answer delivered in July: "The government has no plans to introduce drug consumption rooms. It is for local areas in the UK to consider, with those responsible for law enforcement, how best to deliver services to meet their local population needs."

For those working to reduce the drug death toll on Britain's streets, the message was clear. National government wouldn't fund or provide drug consumption rooms (too politically risky), but if local health and police chiefs thought they were a valuable tool, they could consider them.

And they are. In Glasgow, the NHS has bought a building in the city centre to adapt into Britain's first drug consumption room. The plans include space for 12 injecting booths and an inhalation room.

'Enforce the law'

The police and crime commissioner for North Wales, Arfon Jones, is working on plans to open a drug consumption room in Wrexham. He had been impressed by the crime reduction credited to a DCR he visited in Geneva in Switzerland earlier this year.

But when I rang up the Home Office for a response to the consumption room plans, the tone and substance of their response was very different to the one they had given to the ACMD.

"A range of offences are likely to be committed in the operation of drug consumption rooms. It is for local police forces to enforce the law in such circumstances and, as with other offences of this type, we would expect them to do so."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt is odd that they never mentioned their expectation that police officers should arrest people running or using drug consumption rooms when replying to the ACMD's suggestion.

One is tempted to say that ministers want to say one thing privately and another publicly.

There is, of course, a very real debate about the wisdom of sanctioning illegal drug use. There may well be opposition from local politicians and residents near a DCR. And there is a significant hurdle in whether such a facility could operate within the current law.

The Home Office told me: "A range of offences are likely to be committed in the operation of drug consumption rooms, such as possession of a controlled drug, being concerned in the supply of a controlled drug, knowingly permitting the supply of a controlled drug on a premises, or encouraging or assisting these and other offences."

There will be many people, including those who have been directly affected by drugs, who think consumption rooms send completely the wrong message and that the correct response must always be the pursuit of abstinence.

But many working in the drugs arena believe DCRs are a way to reduce the harm chronic addiction does to users, their families and friends, as well as wider society.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA number of countries have found ways around the obvious legal difficulties, and drug law experts in Britain don't think these are insuperable barriers.

Rudi Fortson QC, a barrister expert in the field, believes that, even without a change in the law, local police and other agencies might sign a joint agreement in which "discretion is sensibly and pragmatically exercised in the interests of personal and public health and welfare".

He notes that the courts "will not lightly interfere with the exercise of discretion that was reasonable and rational".

A similar challenge was recently made in Canada after the national government tried to close down a local drug consumption room in Vancouver. Judges concluded the facility was saving lives, was in the public interest, and refused to shut it. Other DCRs have since opened in Canada.

Those intending to open DCRs in the UK argue such facilities save lives and save money.

Across Britain, it is pointed out, approximately 165 injecting drug users are infected with HIV each year. The lifetime cost of treatment for an individual is put at £380,000, so each year's infections are likely to cost the NHS £63m. Ninety heroin addicts have become infected with HIV in the last couple of years in Glasgow alone.

The reason this issue is so hard for ministers to navigate is that a chronic drug user is both vulnerable and criminal, at risk of harm and at risk of jail.

The space where those two identities overlap is a political minefield.