Parsons Green: What do the police do next?

This is the fifth terror attack of 2017. And it's the only one this year in which nobody has died.

Earlier this summer, the Metropolitan Police commissioner Cressida Dick said police believed they had stopped six other significant plots - and there has been at least one more since then.

So, put plainly, this is the most sustained period of terror activity in England since the IRA bombing campaign of the 1970s.

The amount of work that confronts detectives on a day like this is enormous. Hundreds of officers were immediately put on the investigation, with clear goals. These are:

- Who did it?

- Are there more devices?

- Who else, if anyone, was involved?

- How was the device made?

So let's start with that fourth question and work backwards. The people in charge of the investigation into the bomb are scientists from the Forensic Explosives Laboratory.

They investigate every explosive device recovered in the UK. In 2005 they had to look at the devices left behind from the botched attacks of 21 July.

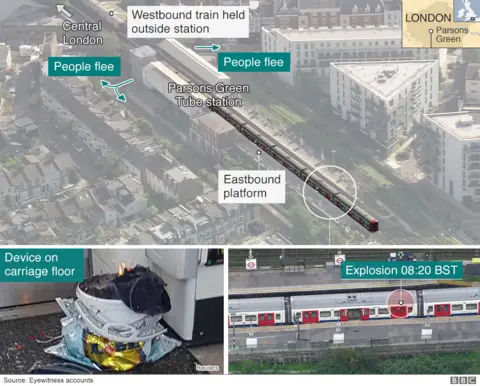

The bomb at Parsons Green was an improvised explosive device (IED) and, like those on 21/7, it didn't work as planned.

PA

PAThe device's initiator appears to have worked - but the main charge did not detonate. This could be because the bomb-maker had got the recipe wrong.

In the case of the 21/7 attacks, the attackers tried to create TATP, an explosive compound made from hydrogen peroxide, commonly sold as hair bleach, and other chemicals.

They added chapatti flour to make the explosion more powerful still. But their chemistry was incompetent - in fact so incompetent that the ringleader had no idea, when he strapped on his rucksack, whether his device was capable of detonating or not.

Met Police

Met PoliceTATP was used in the Manchester Arena attack earlier this year - and it was also the chemical of choice for some of the Paris 2015 attackers and the men behind the Brussels Airport bombing the following year.

The recipe is in wide circulation in publications produced by what remains of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and the separate self-styled Islamic State group.

But don't go looking for it: there have been dozens of "Section 58" prosecutions and jailings for possession of this material. It's a long-standing strategy to restrict the flow of this information.

There are other similarities to previous incidents, including a failed attack on the London Underground last year.

Damon Smith put his homemade device into a rucksack and left it on a Jubilee Line train in October 2016. Here he is getting off the train and leaving the bag behind:

Met Police

Met PoliceHe got the bomb recipe from a jihadist manual, used a cheap clock for a timer, and modified fairy lights acted as an initiator.

The Parsons Green device is also understood to have had some kind of timer and the fairy lights are apparent from the pictures.

Some of them have what looks like a white plug at the end which could be wax.

This approach has been previously used to seal bulbs after they have been modified to be part of a bomb. Zahid Hussain, a Birmingham man convicted in May of trying to make a crude device, did exactly this.

A device with a timer obviously suggests someone left it behind - although it is entirely possible the attacker intended to stay with the bomb until the end.

Another would-be attacker who's now languishing in jail, Haroon Syed, wanted a bomb with a timer in case he messed it up himself. (He didn't know he was talking to an undercover investigator).

Met Police

Met PoliceWorking on the assumption that the attacker left before the detonation, specialist CCTV search officers will have since spent hours trying to ascertain who was carrying the distinctive Lidl freezer bag and its bulky contents onto the Tube.

The London Underground is smothered with CCTV. If the attacker got on south of Parsons Green, rather than doubling back from the north, there are five stations that could have been the entrance point.

Their image would have been captured on scores of cameras during their journey.

Simultaneously, a specialist team of detectives will be following any money trail they can - an increasingly important part of any investigation.

They'll be looking at the payment cards used to enter and leave the London Underground - and whether there is any match to a suspicious purchase of precursor chemicals.

Officers will also have to work out if the attacker was alone. There may even be clues left at the scene.

Very often, it is the sheer incompetence of the would-be terrorist that provides the breakthrough, as the Guardian's Jason Burke has documented in this excellent piece on Friday.

But the arrest of two individuals will not bring an end to the investigation.

Investigators need the evidence that completes a chain from the carriage to a bomb factory (assuming again that they can find it) and a lot of that will come from the work of the Forensic Explosives Laboratory.

One priority will be gathering evidence to prove that the individual intended the device to explode.

In the 21/7 trial the defendants claimed it was all a hoax. So, in the months to come, scientists may construct an exact replica of the device to see how it would have behaved in controlled and safe conditions.

Before that, they need to be able to safely remove the device for further analysis. That is far harder than it sounds. They can't just scoop it up and drive it through London.

During 21/7, the science team carefully took small samples for analysis - but when what remained kept bubbling away, they were forced to destroy it out of fear it could still explode.