Families left devastated by false claims of FGM in girls

Some children in the UK have spent months on child protection plans - or in foster care - on the false suspicion they are victims of female genital mutilation, a BBC report has found.

The BBC understands that it can take months for children to be examined in cases where FGM is suspected.

Children can be separated from their parents while inquiries take place.

Experts say that in the majority of cases, when examined by a specialist, it turns out the child has not had FGM.

Female genital mutilation is a term given to all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitals or other injury to female genital organs where there are no medical reason.

It is usually carried out on girls under the age of 15, with most FGM done under the age of five, according to Unicef.

FGM has been illegal in the UK since 1985 and further legislation in 2003 and 2005 made it an offence to arrange FGM outside the country for British citizens or permanent residents.

For nearly two years, it has been a legal requirement for all health professionals, social workers and teachers to report cases of FGM in under-18s in England and Wales to the police, and is an obligation for professionals to refer suspected cases to local safeguarding teams.

A study by experts at University College London Hospital in 2016 showed it took nearly two months for children to be referred for an examination by local authorities. There have been waits of more than a year. The hospital confirmed this was still a problem.

There are cases where children have been separated from their parents while investigations take place.

A charity that works with families to eliminate FGM in the UK says the way some cases were handled left children and their families traumatised.

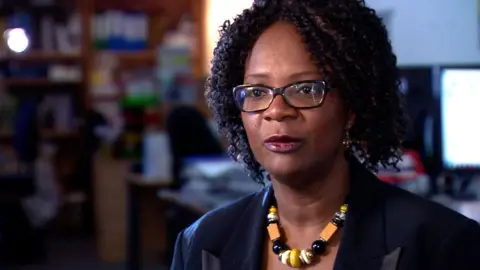

"There's a knee-jerk reaction from professionals when they hear FGM. I don't know whether it's terrified or wanting to make sure something doesn't go wrong. So they really go in too hard," says Toks Okeniyi, head of programmes and operations for the organisation Forward.

Her organisation worked with one family where the child was placed in foster care for eight months before being examined and was found not to have undergone FGM.

"This family said they felt like goats herded into a paddock and nobody cared. It is just a hopeless situation," she said.

One woman, originally from East Africa, whom we are keeping anonymous to protect the identity of her children, told the BBC that police opened an investigation after she asked her midwife a question about FGM.

Her children were placed on a child protection plan because it was believed that she had undergone the procedure and her two daughters may have too.

She denied the accusations and fought for four months to get the medical examination that proved her innocence, but the ordeal had a huge impact.

"I needed an examination done on me and my children. I knew I hadn't undergone FGM, my children hadn't undergone any FGM," she says.

"I knew within myself that I hadn't done anything wrong - my children were fine and healthy and I hadn't hurt them in any way.

"The police officer said to me that if I hadn't had the examination taken for my children, to be sincere, I would have lost my children. Social services would have taken them away."

There are no definitive figures but the British government has warned thousands of women and children are at risk of FGM and has committed to helping to end the practice worldwide within a generation.

In 2015, the former Home Affairs Select Committee chairman Keith Vaz said: "Young girls are being mutilated every hour of every day. This is deplorable. This barbaric crime which is committed daily on such a huge scale across the UK cannot continue to go unpunished."

But some doctors have told the BBC that they do not believe that FGM is taking place on the scale politicians have suggested.

"We're just not seeing the number that we would have thought we would see, given the demographics that we cover now," says Dr Catherine White, clinical director at St Mary's Sexual Assault Referral Centre in Manchester, one of three specialist centres in the UK where children are examined for FGM.

"Perhaps newer generations, younger generations, aren't perpetuating it in the same way... now I know that some of it might be hidden and that it might be done and never come to light to professionals.

"But I think if certain types of FGM were being done at the rates that we were perhaps led to expect we would be seeing cases coming through with infection or bleeding, they would be ending up in front of healthcare professionals and then being referred to us. And that just hasn't happened - not here in Greater Manchester anyway."

Experts from across the country told the BBC that most confirmed cases were historic and had taken place abroad.

Since mandatory reporting came in, there have been more than 40 referrals in Manchester, of which 14 were confirmed as cases of FGM. All had been performed before the child came to the UK.

A similar picture was found in Birmingham, where all nine confirmed cases of FGM between April and August this year were in children who had had the procedure before moving to the country.

So far no-one has been successfully prosecuted in the UK.

A government spokesperson said: "Female genital mutilation is a horrific act of abuse which this government is working to tackle.

"We know that by its nature FGM is a hidden crime and the government is committed to improving our understanding of the scale and nature of it in the UK."

More on this story on The World at One on Radio 4 and BBC Newsnight at 22:30 on BBC Two