Gay rights 50 years on: 10 ways in which the UK has changed

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexual sex in England and Wales. How did the law change society?

1. Social approval of same-sex relationships has risen rapidly

The proportion of the British public who say they approve of same-sex partnerships has soared over the past 30 years.

Since 1983 the British Social Attitudes survey has asked people whether they think sexual relationships between two adults of the same sex are "always wrong, mostly wrong, sometimes wrong, rarely wrong or not wrong at all".

The group of people answering that they thought same-sex partnerships were "not wrong at all" has almost quadrupled from 17% when the survey started in 1983, to 64% in 2016.

Approval fell in the 1980s when the Aids crisis and the introduction of section 28 - a law prohibiting the promotion or teaching of homosexuality in schools - could have swayed public opinion according to NatCen, the think tank which runs the survey.

But a steady and rapid rise from the early 1990s reflects a wider trend of social liberalisation, something also seen in changing attitudes to pre-marital sex.

PA

PAApproval of pre-marital sex grew initially among the young - as they got older they retained that belief, and soon both old and young were more liberal on the issue.

For same-sex relationships the shift in attitude has been quicker - not only did young people with liberal views get older, but older people changed their minds, too.

This might in part be because changes in the law, such as the legalisation of civil partnerships and then gay marriage, have a powerful influence on people's views, a NatCen spokesman suggests.

2. 1967 was not the end of the story

While the 1967 act was a milestone in equality, it was far from the end of the story - and it chiefly benefited men who had sex with men.

There have been a number of other key dates on the journey towards sexual and gender equality, not just for gay men but for the rest of the LGBT community.

For example, gay sex remained illegal in Scotland and Northern Ireland until 1982 while transgender people weren't protected in equality legislation until 2010.

50 years of legislation

1967 - Sex between two men over 21 and "in private" is decriminalised

1980 - Decriminalisation in Scotland

1982 - Decriminalisation in Northern Ireland

1994 - The age of consent for two male partners is lowered to 18

2000 - The ban on gay and bisexual people serving in the armed forces is lifted; the age of consent is equalised for same- and opposite-sex partners at 16

2002 - Same-sex couples are given equal rights when it comes to adoption

2003 - Gross indecency is removed as an offence

2004 - A law allowing civil partnerships is passed

2007 - Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is banned

2010 - Gender reassignment is added as a protected characteristic in equality legislation

2014 - Gay marriage becomes legal in England, Wales and Scotland

3. Criminalisation of gay people continued into this century

In 1967, homosexuality was only partially decriminalised.

Those keen to criminalise any public displays of consensual homosexual activity still had tools to do so through the offence of "gross indecency", which had a broad interpretation.

Prosecutions for relationships between two consenting men over the age of 16 continued until 2000 when the age of consent was equalised. In the years following the 1967 law change, even public displays of affection could be criminalised as "procuring" or "soliciting".

Gross indecency covered activities ranging from having sex in public, to sexual activity in private involving more than two men. Hotels were counted as public and so men could be prosecuted for meeting there while others were convicted as recently as 1998 for having group sex in private.

After the 1967 Act, activities that had not been decriminalised were prosecuted far more strictly than before, according to human-rights barrister Alex Bailin QC. This led to a steep rise in offences of gross indecency. After a decline there was another spike in the 1980s amid a moral panic over the Aids epidemic.

Sexual activity in a public toilet remains a specific offence to this day - for opposite-sex couples as well. Prosecutions were far more common until the 1990s but have tailed off since, partly because of social attitudes to gay relationships, says Kate Goold, a solicitor at Bindmans.

4. Government has attempted to redress this legacy

Given this legacy of criminalisation, the government introduced a scheme in October 2012 allowing those prosecuted under defunct gay-sex-related laws, to have their convictions removed from police and court records.

Criminalisation of gay men

Convictions from 1950s-2000

50,000

gay sex-related convictions

-

16,000 still living in 2012

-

242 people applied to have their records wiped

-

83 applications granted between 2012 and 2016

The Home Office estimates that there were about 50,000 such offences recorded on the system from the 1950s until 2000.

But of these 50,000, only an estimated 16,000 are for people who are still living and so able to apply.

Not all of the 16,000 offences are eligible to be "disregarded". They include some where the activity was non-consensual, with a person under 16 years of age, or involving other activity which would still be a crime today - for example having sex in a public toilet.

Between October 2012 and April 2016, only 242 people applied for a disregard and only 83 were granted, according to a written answer in parliament.

The law changed further in 2016. Family members can now apply for posthumous pardons.

Getty Images

Getty Images5. Recording of homophobic hate crimes has risen

A steep rise in homophobic hate crimes has been recorded over the past five years, but this is thought to be in large part down to an increase in people reporting incidents rather than a genuine rise in crime.

The National Police Chiefs Council's lead on homophobic crimes, Assistant Chief Constable Mark Hamilton, says: "Traditionally, homophobic hate crime has been significantly under-reported and we do not believe that current statistics accurately reflect actual levels of abuse.

"However, higher reporting rates indicate that the LGBT community feels increasingly confident to come forward and report incidents."

The Home Office's report on the latest figures says that "these could be genuine increases in hate crimes or increases in the numbers of victims coming forward to report a hate crime".

6. Young people are more likely to identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual

Public opinion has shifted hugely on same-sex relationships over the past decade.

It's striking that people aged 16-24 are more than five times more likely than those aged over 65 to identify as gay, lesbian or bisexual.

The Office for National Statistics keeps records of people who identify themselves as gay, lesbian or bisexual - 1.7% of the adult population (2% of men and 1.5% of women). This is likely to underestimate the real numbers as the survey doesn't capture sexual attraction or behaviour.

In 2005 the government tried to estimate the size of the lesbian, gay and bisexual population and came up with a larger number - 5-7% of the population.

7. Gay people say they feel less happy than their straight peers

People who identify as gay, lesbian and bisexual report lower levels of well-being than heterosexuals in the UK.

The ONS looks at happiness, life satisfaction, and the extent to which people feel their life is worthwhile. For all three of those categories, gay, lesbian and bisexual people report much lower levels.

Data is also collected on anxiety, which has the biggest sexuality gap. Gay and lesbian people report higher levels of anxiety than straight people, but bisexual people are even more likely to suffer from the condition.

Young lesbian, gay and bisexual people are also more likely to suffer from suicidal thoughts than their straight friends, according to a 2014 survey by LGBT support charity Metro. The results also suggested higher rates of self-harm.

8. Same-sex couples have gained equal marriage rights

Civil partnerships were legalised in 2004 throughout the United Kingdom, with the first ceremonies taking place at the end of the following year.

Nearly 140,000 people entered into civil partnerships between 2005 and 2015, the last year for which figures are available.

Civil partnerships and marriages

2005

first civil partnership took place

2014

first same-sex marriage took place

-

140,000 people entered into civil partnerships in the UK between 2005 and 2015

-

60,000 people were in same-sex marriages in 2016

Across the UK, gay and lesbian couples were granted many of the same rights as married heterosexuals, albeit with a few differences around issues like private-sector pensions.

It meant that couples could no longer be kept out of hospital rooms when their partner was sick, they would no longer lose their home or business because of tax laws, and they had parental rights over children.

Same-sex marriage was legalised a decade later, with the first ceremonies taking place in England, Wales and Scotland in 2014. It is still banned in Northern Ireland. According to official estimates about 60,000 people were in same-sex marriages in 2016.

9. Gay marriage is now legal in 22 countries

England, Scotland and Wales were far from the first places to legalise same-sex marriage. The Netherlands changed the law first in 2001.

Gay marriage is now legal in 22 countries worldwide, according to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA). That's just 11% of UN member states.

Definitions can sometimes be tricky though - the UK is included despite Northern Ireland's ban. Brazil and Mexico are also on ILGA's list because "through one legal route or another, it appears to be possible to marry in most jurisdictions".

Germany is not included - MPs gave their approval to same-sex marriage earlier this year but the law does not come into force until October.

Countries where gay marriage is legal

2001 Netherlands

2003 Belgium

2005 Canada, Spain

2006 South Africa

2009 Norway, Sweden

2010 Iceland, Portugal, Argentina

2012 Denmark

2013 Uruguay, New Zealand, France, Brazil

2014 UK (excluding Northern Ireland)

2015 Luxembourg, Ireland, Mexico, USA

2016 Colombia

2017 Finland

A further 28 countries guarantee some civil-partnership recognition according to ILGA.

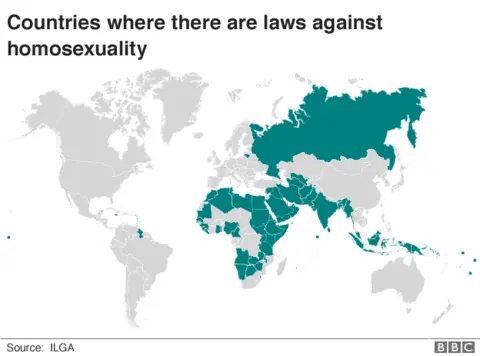

10. Being gay is still criminalised in many parts of the world

Britain is marking 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality but same-sex relations are still illegal across vast swathes of the world.

There are 72 countries which explicitly outlaw homosexuality, according to ILGA, but there are several others with some form of legal restriction.

For example, Russia is included even though same-sex relationships were formally legalised in 1993. This is because "a variety of repressive legal provisions" have come into force over the past decade, according to ILGA.

In eight countries same-sex relationships sometimes carry the death penalty - Iran, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria, and parts of Iraq and Syria held by so-called Islamic State.

The number of states that criminalise same-sex relations is decreasing annually, though, with Belize and the Seychelles repealing such laws last year.