The tech flaw that lets hackers control surveillance cameras

Getty Images

Getty ImagesChinese-made surveillance cameras are in British offices, high streets and even government buildings - and Panorama has investigated security flaws involving the two top brands. How easy is it to hack them and what does it mean for our security?

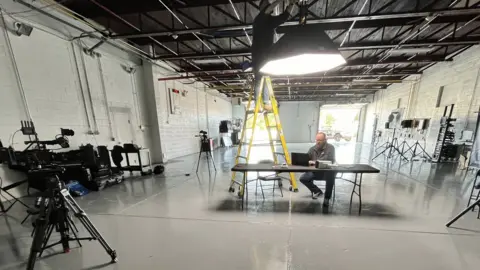

In a darkened studio inside the BBC's Broadcasting House in London, a man sits at his laptop and enters his password.

Thousands of miles away, a hacker is watching everything he types.

Next, the BBC employee picks up his mobile phone and enters the passcode. The hacker now has that, too.

A security flaw in the surveillance camera on the ceiling - manufactured by the Chinese firm Hikvision - means it's now vulnerable to attack.

"I own that device now - I can do whatever I want with that," says the hacker. "I can disable it… or I can use it to watch what's going on at the BBC."

Thankfully for the man being watched, the hacker is working with the BBC. This is part of a series of experiments by Panorama to test the security of some Chinese-made surveillance cameras.

Hikvision and Dahua are two of the world's leading manufacturers of surveillance cameras.

Nobody knows how many of their units line the UK's streets.

Last year, the privacy campaign group Big Brother Watch attempted to find out. Between August 2021 and January 2022, it submitted 4,510 Freedom of Information requests to public bodies across the UK. Of 1,289 that responded, 806 confirmed they used Hikvision or Dahua cameras - 227 councils and 15 police forces use Hikvision, and 35 councils use Dahua.

Hikvision cameras are used to monitor many government buildings too - in a single afternoon in central London, Panorama found them outside the Department for International Trade, the Department of Health, the Health Security Agency, Defra and an Army reserve centre.

Security experts fear the cameras have the potential to be used as a Trojan horse to play havoc with computer networks, which in turn could spark civil disruption.

Prof Fraser Sampson, the UK's surveillance camera commissioner, warns the country's critical infrastructure - including power supplies, transport networks and access to fresh food and water - is vulnerable.

"All those things rely very heavily on remote surveillance - so if you have an ability to interfere with that, you can create mayhem, cheaply and remotely," he says.

Charles Parton of the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi), a former diplomat who worked in Beijing, agrees: "We've all seen the Italian Job in our youth, where you bring the whole of Turin to a halt through the traffic light system. Well, that might have been fiction then, it wouldn't be now."

Hikvision told Panorama it is an independent company and is not a threat to UK national security.

"Hikvision has never conducted, nor will it conduct, any espionage-related activities for any government in the world," it said, adding that its "products are subject to strict security requirements and are compliant with the applicable laws and regulations in the UK, as well as any other country and region we operate in".

Panorama worked with US-based IPVM, one of the world's leading authorities on surveillance technology, to test whether it was possible to hack a Hikvision camera. IPVM supplied the one that was installed in a BBC studio.

Panorama could not run the camera on a BBC network for security reasons - so it was put on a test network where there is no firewall and little protection.

The camera Panorama tested contains a vulnerability discovered in 2017. IPVM's director Conor Healy describes this as "a back door that Hikvision built into its own products."

Hikvision says its devices were not deliberately programmed with this flaw and it points out that it released a firmware update to address it almost immediately after it was made aware of the issue. It adds that Panorama's test is not representative of devices that are operating today. But Conor Healy says more than 100,000 cameras online worldwide are still vulnerable to this issue.

As Panorama's hacking experiment begins, Conor and IPVM's research engineer John Scanlan are sitting behind laptops in their Pennsylvania headquarters.

Hacking a computer system without permission is a criminal offence - so Panorama is not providing all of the details of how they do it.

Healy and Scanlan start by locating the camera inside Broadcasting House, then go to work attacking its security.

Then Healy times how long it takes to seize control of it. Just 11 seconds later, Scanlan announces: "We have access to that camera now."

They can now see inside the studio - including the Panorama employee on his laptop.

"If we zoom in tight on the keyboard, we can see clearly the keys that he's pressing to put his password in," Scanlan says.

"This is akin to a locksmith giving you a key to your home and the secretly making a master key for all of the locks in that community… that's effectively what Hikvision engineers did."

From spy balloons to secret police stations and dissidents on the run, Panorama investigates China's global surveillance operation. We reveal new details about Beijing's fleet of spy balloons - and hack a Chinese-made security camera to show how similar devices that line our streets could be exploited.

Watch on BBC One at 20:00 (20:30 in Wales) on Monday 26 June - and afterwards on BBC iPlayer (UK only)

Hikvision says its "products do not have a 'backdoor'" and were not deliberately programmed with this flaw. It adds it believes that nearly all of the local authorities using their devices would have updated their cameras long before now.

Next, the hackers begin their second test - accessing Dahua's cameras by infiltrating the software that controls them.

Two test cameras have been set up in IPVM's headquarters. If the hackers are successful, they could take charge of an entire network of surveillance cameras.

Soon they find the software vulnerability. "There we go, we're in," says Healy.

Now they are inside the system, they can use a camera to eavesdrop.

"What a lot of people don't realise about these cameras is that a large majority of them have microphones," Healy explains, and while users often switch these off, it's easy for hackers to switch them back on again - in effect, "wiretapping" the room.

Dahua says when it was made aware of the vulnerability late last year it "immediately conducted a comprehensive investigation" and quickly fixed the problem through "firmware updates".

The company also says it is not state-backed and that its equipment could not interfere with the UK's critical infrastructure. It adds: "These allegations are untrue and paint a highly misleading picture of Dahua Technology and its products."

But experts say the UK needs to do more to protect itself from what Prof Sampson, the surveillance camera commissioner, describes as "digital asbestos".

"We have a previous generation that has installed this equipment, largely on the basis that it was cheap and got the job done," he says. "We've now realised that it has some serious and inherent risks - so what do we about it?"

Asked whether he trusts Hikvision and Dahua, he replies: "Not one bit."