Asteroid mining: Helping to meet Earth's natural resource demands

Asteroid Mining Corporation Ltd

Asteroid Mining Corporation Ltd"They essentially hold on to the side of the asteroid for dear life as it screams through the solar system."

Mitch Hunter-Scullion is describing a six-legged robot called Scar-e, the Space Capable Asteroid Robotic Explorer, which he aims to send to an asteroid to drill for precious metals such as iron, nickel and platinum.

As well as being increasingly essential for phones, laptops and cars, some metals like platinum will also be needed to help produce hydrogen as we transition to greener energy.

With only a finite supply of them on earth - people are increasingly looking to space to meet this increased demand.

That's where Scar-e comes in. Its powerful claw, designed in partnership with Tohoku University in Japan, should grip on to an asteroid in space to stop it from floating away.

It has been inspired by the way tarantulas hang on to walls.

AMC/Space Robotics Lab at Tohoku University

AMC/Space Robotics Lab at Tohoku University"I am terrified of spiders", Mitch says, "so I thought that was quite appropriate."

Mitch is the founder of the Asteroid Mining Corporation (AMC). He admits pulling off such a feat is still a fair way off.

Not only would it involve landing robots on a rock, but also remotely building mining infrastructure, and then somehow sending the materials back to Earth.

But it's easy to see why he and others want to give it a try.

A new gold (or platinum) mining rush?

Asteroids are made of the same stuff as the rest of the rocky planets in our solar system - and that means they are also rich in some precious minerals we go to great lengths (and depths) to mine here on Earth.

Finding large deposits of platinum on an asteroid, for example, says Mitch, "would allow humanity to start innovating in a way we haven't done in quite a while".

Getting resources out of asteroids presents a different challenge to getting them from Earth, says Prof John Bridges, a University of Leicester scientist involved in the Hayabusa2 mission.

This is because these small, inert space rocks have not undergone the same geological processes as their massive planetary cousins.

"They haven't gone through the… melting, volcanism and mountain forming, which act to concentrate some of the elements in particular parts of the crust. So that's why on Earth we can have a mine [in a particular place] to extract rare earth elements."

On an asteroid, "all the elements will still be there", he says, "but they'll just be scattered. Nature hasn't had a chance to concentrate it into ore veins, for example".

And that means asteroid miners would have to process an awful lot of material, for it to be worthwhile.

Prof Bridges believes commercial space mining is a "fascinating area", but is doubtful it will solve the world's resource problem.

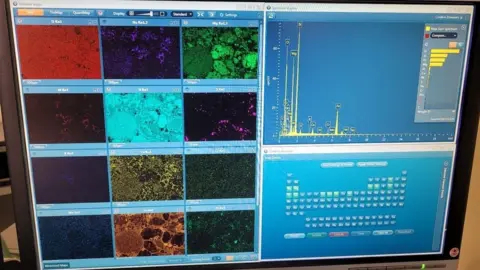

The trick, Mitch says, will be finding the right asteroid. And that's where Dr Natasha Stephen and her electron microscope come in.

The rock star that fell to Earth

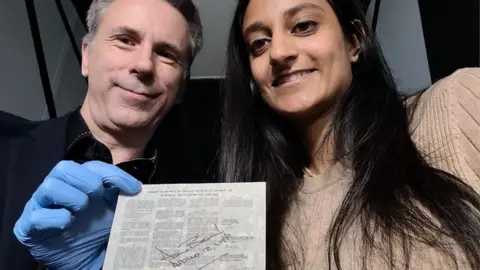

I never thought I'd touch a piece of the Moon, but that's what's in my hand at the Plymouth Electron Microscopy Centre.

It's a small piece of meteorite which fell to Earth in the Sahara, and has been identified as a fragment of Moon rock flung into space by a previous impact on the lunar surface.

Many meteorites come not from the Moon, however, but from asteroids, and Natasha is using the electron microscope to catalogue the elements contained within them.

And the hunt is on for meteorites, and hence their parent asteroids, that are rich in the right kind of stuff.

"If we find a concentration of platinum in one of our meteorites," she explains, "we can tell the AMC guys … now it's over to you. Go and find that type of asteroid in the data."

Who owns space?

Once a promising asteroid has been identified, though, there's the tricky matter of working out to whom it belongs.

Dhara Patel, from the UK's National Space Centre, explains that when it comes to who owns what, space law is not fit for purpose.

Nothing has yet been written about whether any one nation or company can claim ownership over an asteroid, parts of the Moon, or the riches that lie beneath the surface.

And when the rewards could run into trillions of pounds, it's easy to see how disputes, legal battles, and even real battles could occur.

National Space Centre

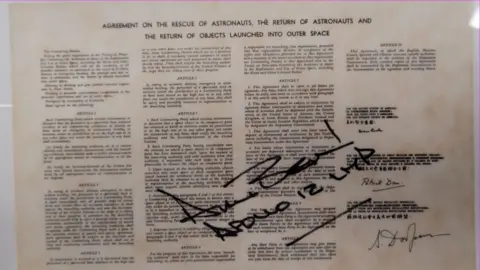

National Space CentreIn 1966, the United Nations (UN) drew up the Outer Space Treaty, which attempted to stop nations from misusing and mistreating space, and which was signed up to by more than 100 countries.

"The Outer Space Treaty says 'space is the province of all mankind'. The problem is that it lacks detail," Dhara says.

"We're using a treaty that was formed over 50 years ago, and space exploration has developed a lot since then."

Nasa, now planning a return to the Moon, has drafted its Artemis Accords - a more detailed set of principles focused on exploration of the Moon, Mars and other celestial bodies.

But these are still vague on whether any company or nation can claim ownership over resources extracted.

Several countries have signed up to the Artemis Accords, but Dhara believes we need a global approach.

"It probably starts with using the UN as a baseline, and making sure policies we put in place…are on an international level."

Mitch is confident, however, that under existing principles, there are existing rules that protect early miners.

"Whoever gets there first would have priority rights."

So first-come, first-served, basically. It could just be one big gold rush after all.

All of this is, of course, decades away from reality, and whether it will be entrepreneurs like Mitch, mega-billionaires like Elon Musk, or entire nations that end up becoming master-miners is anyone's guess.

Find out more about asteroid mining on the latest episode of BBC Click.