Why is there a chip shortage for computers and cars?

Getty Images

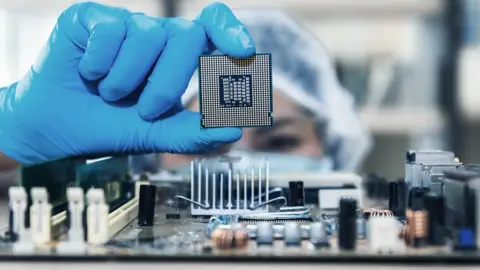

Getty ImagesFor the most part they go unseen but computer chips are at the heart of all the digital products that surround us - and when supplies run short, it can halt manufacturing.

There was a hint of the problem last year when gamers struggled to buy new graphics cards, Apple had to stagger the release of its iPhones, and the latest Xbox and PlayStation consoles came nowhere close to meeting demand.

Then, just before Christmas 2020, it emerged the car industry was facing what one insider called "chipageddon".

New cars often include dozens of microprocessors - and manufacturers were quite simply unable to source them all.

Toyota has since warned that its global vehicle production will be slashed by 40% in September 2021 as a direct result.

And one technology company after another has warned they too face constraints.

Samsung is struggling to fulfil orders for the memory chips it makes for its own and others' products.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd Qualcomm, which makes the processors and modems that power many of the leading smartphones and other consumer gadgets, has the same problem.

Pandemic's impact

Like much else wrong with the world, the coronavirus is partly to blame.

Lockdowns fuelled sales of computers and other devices to let people work from home - and they also bought new gadgets to occupy their time off.

The automotive industry, meanwhile, initially saw a big dip in demand and cuts its orders.

As a result, chipmakers switched over their production lines.

But then, in the third quarter of 2020, sales of cars came roaring back more quickly than anticipated, while demand for consumer electronics continued unabated.

5G infrastructure

With existing foundries running at capacity, building more is not a simple matter, though.

"It takes about 18 to 24 months for a plant to open after they break ground," analyst Richard Windsor says.

"And even once you've built one, you have to tune it and get the yield up, which also takes a bit of time.

"This isn't something you can simply switch on and switch off."

The rollout of 5G infrastructure is also adding to demand.

And Huawei put in a big order to build up a stockpile of chips before US trade restrictions blocked it from ordering more.

By contrast, the car industry is relatively low margin and tends not to stockpile supplies, which left it in a pinch.

Getty Images

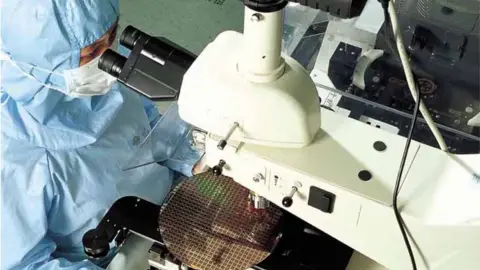

Getty ImagesRecently, TSMC and Samsung, the leading chip producers, have spent billions getting a new highly complex 5-nanometre chip-manufacturing process up to speed to power the latest cutting-edge products.

But analysts say more widely, the sector has suffered from under-investment.

"Most of tier-two foundries have been registering poor earnings, low margins and high debt ratio during the past few years," a report from Counterpoint Research said.

"From the profitability perspective, building a new fab[rication plant] for smaller foundries is difficult to consider."

And many of these chip producers will instead respond to the extra demand by increasing their prices.

Knock-on effects

Experts do not expect chip scarcity to be resolved any time soon.

Chip designer Intel has warned that it could take two years to catch up with demand.

"We expect semiconductor industry supply constraints on both wafer and substrates to only partially ease in second-half 2021, with some leading-edge (computing, 5G chips) tightness to extend into 2022," a Bank of America research note says.

And one chipmaker told the Wall Street Journal backlogs were now so big, it would take up to 40 weeks to fulfil any order a carmaker put in today.

This could have expensive knock-on effects.

The consultancy AlixPartners forecast the automotive industry will lose $64bn (£47bn) of sales because it has had to close or reduce output.

Although, that sum needs to be viewed in the context of the sector typically generating about $2tn of sales a year.

Monopoly producers

There are also geo-political implications.

The US still leads in terms of developing the components' designs.

But Taiwan and South Korea dominate the chip-manufacturing industry.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co Ltd

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co LtdAnd TM Lombard economist Rory Green estimates the two Asian nations account for 83% of global production of processor chips and 70% of memory chips.

"Like Opec was for oil, Taiwan and South Korea are near monopoly producers of chips," he wrote, adding their market share was set to grow further,

That has raised concern in the States, where one lobby group called the current crisis the "canary in the coal mine" for future supply-line shortages.

And a group of 15 senators has written to President Biden urging him to take action to "incentivise the domestic production of semiconductors in the future".

But arguably the country most affected is China, which makes more cars than any other nation.

Research company IHS predicts 250,000 fewer vehicles will be produced in the country during the first three months of the year as a consequence.

Chinese military

Beijing has long wanted to make the country more self-sufficient in semiconductors in any case.

But the US has taken steps to block local companies making use of American know-how to do so, on the grounds they also supply the Chinese military.

The current crisis will not only give China's leaders cause to redouble their efforts.

It also exposes how disruptive another of their ambitions would be - unification with Taiwan.

'More expensive'

For now, consumers planning a purchase need to bear a few things in mind.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWaiting times for some car models will increase.

And some gadgets may also become hard to find.

The biggest players, such as Samsung and Apple, have the buying power to ensure they have priority.

But smaller brands may be disproportionately affected.

"That means products could get more expensive - or at least not fall in price over time as you would normally expect," Ben Wood, from the CCS Insight consultancy, says.

"And supply will be limited.

"So if there's a gadget you really want to get, don't think about hanging around to see if there's a better deal in a few months' time."