Coronavirus: Ireland's Covid Tracker app is out - where's England's?

BBC

BBCThis morning I installed Ireland's just-released contact-tracing app on my phone, where it joined Germany's Corona Warn-App, which was released three weeks ago.

Gibraltar recently released its Beat Covid Gibraltar app, based on the Irish code.

The Republic's Covid Tracker software is also the foundation of an app Northern Ireland is promising to release within weeks. And now there's a hint Wales could go the same way.

"We remain in discussion about a range of options to achieve a working app, including development in Northern Ireland," a Welsh Government spokesman told the BBC.

Health Service Executive

Health Service ExecutiveSo when is England finally going to get its app?

It is still "urgent and important", the new head of the NHSX contact-tracing app project said yesterday.

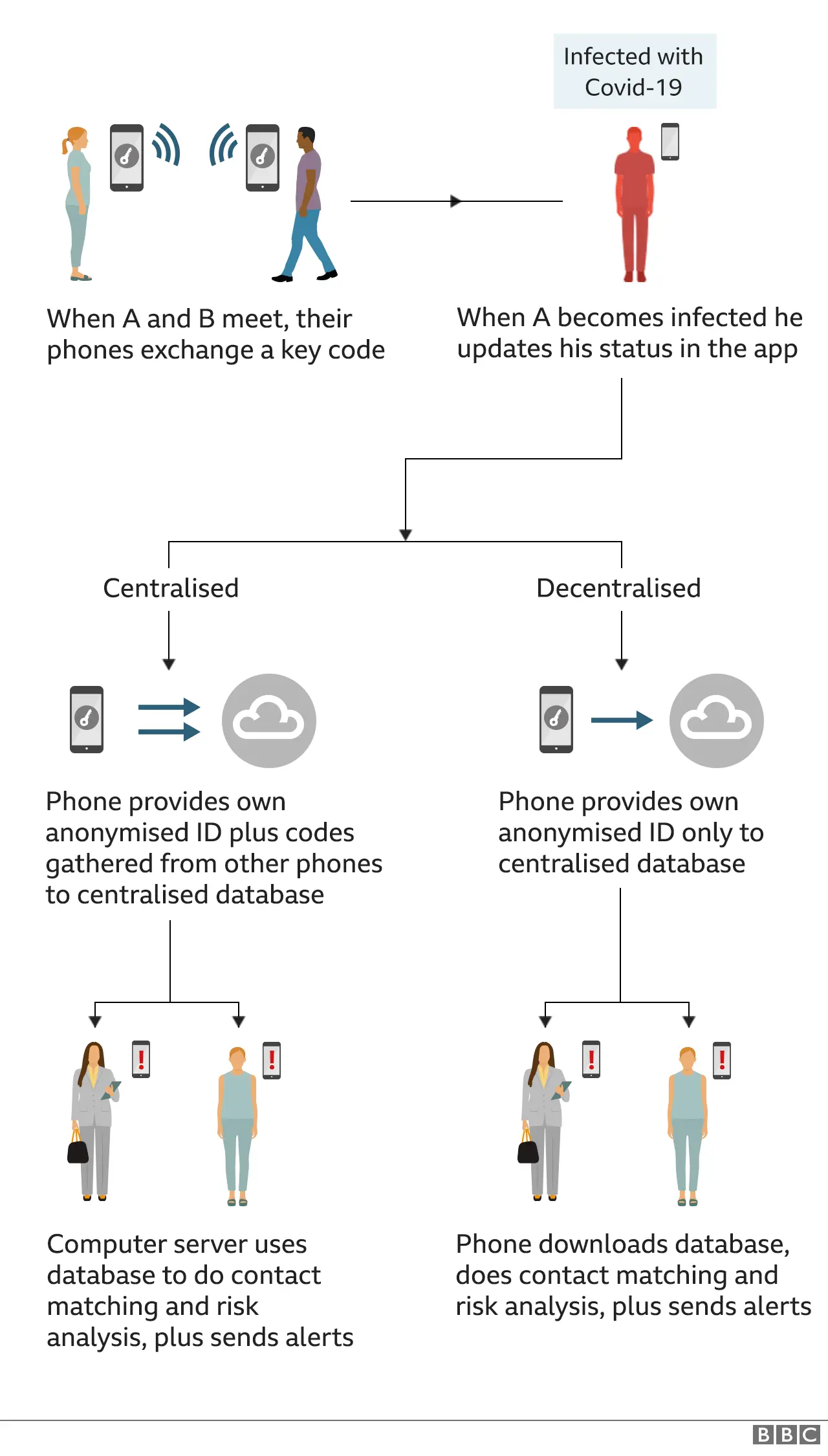

The project lurched to a halt in mid-June, when Health Secretary Matt Hancock and Test and Trace supremo Baroness Dido Harding announced a "centralised" design had failed.

The focus henceforth would be on building a "decentralised" app with the toolkit offered by Apple and Google, which is also being used by Germany and Ireland among a growing list of others.

On Monday, Baroness Harding gave evidence to the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee alongside Simon Thompson, the Ocado executive she drafted in to take responsibility for the app.

Mr Thompson started by saying how urgent it was to get the job done. He went on to stress that collaboration with other countries and with Google and Apple meant that "we have growing confidence that we will have a product that will be good, so that the citizens can trust it in terms of its basic functionality".

But neither he nor Baroness Harding was willing to commit to any timeframe to launch the tech. And both suggested there were still issues with the accuracy of Bluetooth as a way of measuring the proximity of contacts.

Baroness Harding made it clear that she was not going to be hurried just because our neighbours were releasing apps, telling the committee "it's not something that we think that anyone in the world has got working to a high enough standard yet".

Bluetooth doubts

Now it is true that there is very little evidence that Bluetooth-based apps have so far been successful in tracking down people who came close to someone diagnosed with the virus.

People who point to the success of countries like South Korea ignore the fact that its efforts have been based not on Bluetooth but on the use of mass surveillance data, which would almost certainly prove unacceptable here.

Scientists at Trinity College in Dublin who advised the Irish app development team have produced a number of studies showing Bluetooth can be a very unreliable way to log contacts.

After tests on a bus they warned "the signal strength can be higher between phones that are far apart than phones close together, making reliable proximity detection based on signal strength hard or perhaps even impossible".

'Good enough'

Germany has celebrated the fact that in three weeks its app has been downloaded by 15 million people out of a population of 83 million. But there is little or no information about whether it is performing well in its core mission of contact tracing.

Then again, countries like Germany, Ireland and Switzerland have taken the view that an app does not have to be technically perfect, and that if there is any chance of it making even a small contribution to the battle against the virus, it's worth a go.

Robert Koch Institute

Robert Koch InstituteBack in March and April, when the NHSX team had been instructed to move as quickly as possible to build an app, I heard a similar message.

When I questioned whether Bluetooth could really do the job, an official told me that apps were public health tools, not scientific measuring instruments. He added that their accuracy should be measured against humans, who would be pretty poor at remembering how close they were to someone and for how long.

Now the policy appears to be that only something perfect will win the public's trust. This appears to be part of a wider change of strategy that has seen the government move from a technology-led initiative to one that sees an app as the "cherry on the cake".

Countries like Germany might be tempted to point out that they have had that "cake" in the form of an effective manual tracing programme all along, while back in late March the UK had to turn to technology because it just did not have the people in place to do the job.

Incidentally, if public trust is vital to the app's rollout, the people of the Isle of Wight may have something to say about that.

Following the trial of the original, scrapped NHSX app on the island, some residents have been asking what will happen to their data. We've asked too - and have yet to receive an answer.

The view from Belfast

By Luke Sproule

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the Covid Tracker app has been launched by the Health Service Executive (HSE) in the Republic of Ireland, people living across the border in Northern Ireland are able to download it and use it.

Its terms and conditions state that it is intended to be used by anyone living in or visiting the island of Ireland.

They also state that its availability for people living or visiting in Northern Ireland "is intended to help us to inform people living in border areas and to trace cases in those areas".

Anyone using the app in NI is able to activate the contact tracing facility and can also self-report symptoms using the "Covid Check-In section".

However, in the section which asks users to enter personal details, including gender and age-range, those living in Northern Ireland can't add their county of residence. Only counties in the Republic of Ireland are listed - not the six in NI.

It isn't yet clear what impact this has on the functionality of the app for NI users.