Coronavirus: German contact-tracing app takes different path to NHS

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGermany's forthcoming coronavirus contact-tracing app will trigger alerts only if users test positive for Covid-19.

That puts it at odds with the NHS app, which instead relies on users self-diagnosing via an on-screen questionnaire.

UK health chiefs have said the questionnaire is a key reason they are pursuing a "centralised" design despite privacy campaigners' protests.

Germany ditched that model in April.

And on Wednesday Chancellor Angela Merkel said there would be a "much higher level of acceptance" for a decentralised approach, which is designed to offer a higher degree of anonymity.

EPA

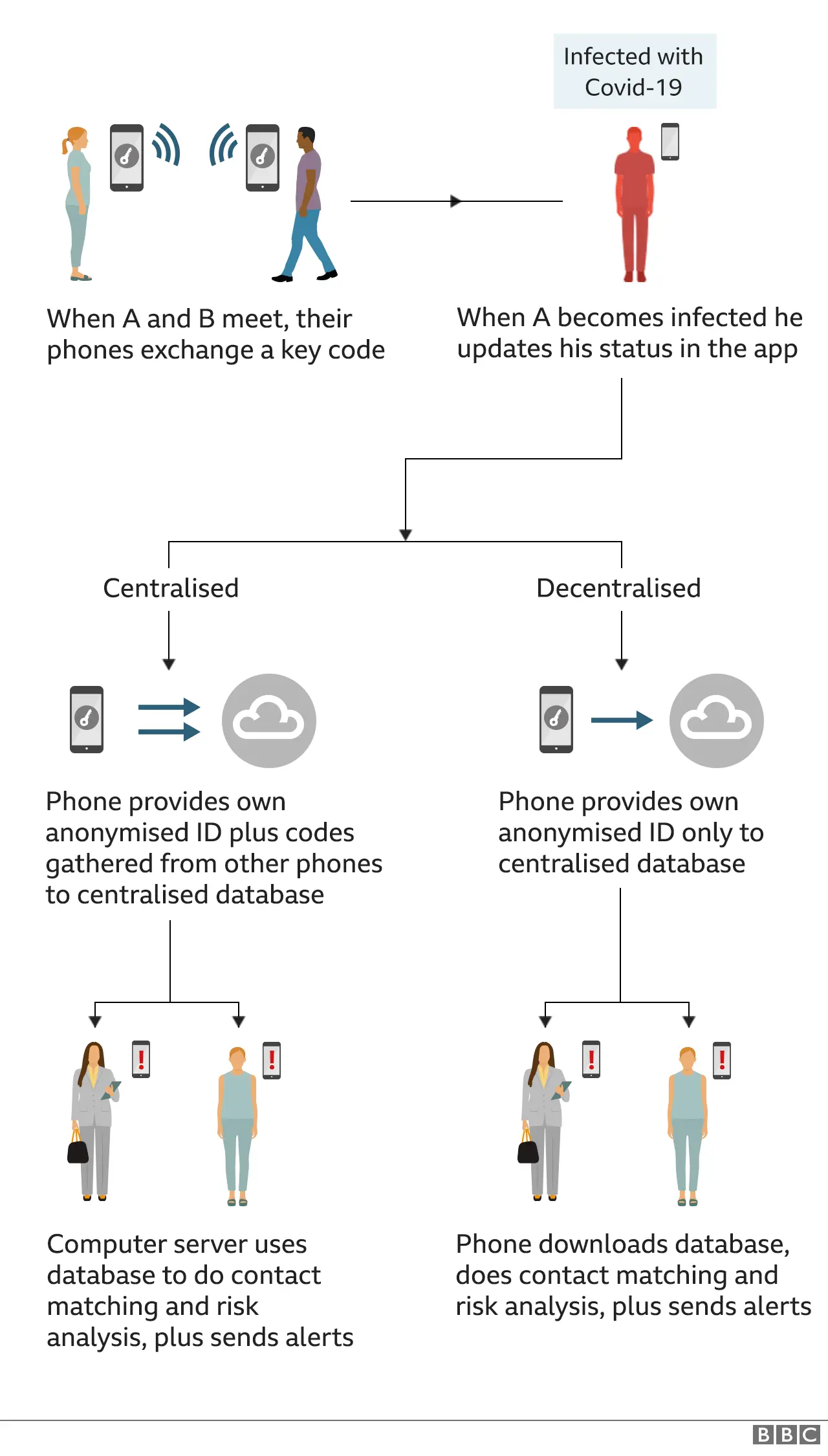

EPAAutomated contact tracing uses smartphones to register when their owners are in close proximity for significant amounts of time.

If someone is later found to have the virus, a warning can be sent to others they may have infected, telling them to get tested themselves and possibly go into quarantine.

In the centralised model, the contact-matching happens on a remote computer server.

And the UK's National Cyber Security Centre has said this will enable it to catch attackers trying to abuse the self-diagnosis system.

By contrast, the decentralised version carries out the process on the phones themselves.

And there is no central database that could be used to re-identify individuals and reveal with whom they had had spent time.

BBC News technology correspondent Rory Cellan-Jones said: "The NHS is taking a big gamble in choosing to alert app users when they have been in contact with someone who has merely reported symptoms.

"It could make the app fast and effective - or it could mean users become exasperated by a blizzard of false alarms."

Ms Merkel said SAP and Deutsche Telekom - which are co-developing Germany's app - were waiting for Google and Apple to release a software interface before they could complete their work.

And BBC News has learned the two US technology companies plan to release the finished version of their API (application programming interface) as soon as Thursday.

False alerts

Details of Germany's Corona-Warn-App published on the code-sharing site Github say it depends solely on medical test results to "avoid misuse".

Those who test positive will be given a verification code that must be entered into the app before it anonymously flags them as being a risk to others.

Germany has led the way in testing in Europe and currently has capacity to analyse about 838,000 samples per week.

The UK is catching up - but scientists advising the NHS say they can save more lives by also drawing on self-diagnosis data.

"Speed is of the essence," Prof Christophe Fraser, of the Oxford Big Data Institute, said last week.

It can take several days to obtain Covid-19 test results.

And self-reported symptoms can be acted on instantly.

But an ethics advisory board advising Health Secretary Matt Hancock on the app has warned too many resulting "false positive alerts could undermine trust in the app and cause undue stress to users".

- LOCKDOWN UPDATE: What's changing, where?

- SCHOOLS: When will children be returning?

- EXERCISE: What are the guidelines on getting out?

- THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

- AIR TRAVELLERS: The new quarantine rules

- LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

- GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the pandemic

- RECOVERY: How long does it take to get better?

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

The NHS is currently trialling its app on the Isle of Wight.

But a Department of Health spokeswoman said this had been expected.

"In a matter of days, more than 50,000 people have downloaded the app with overwhelmingly positive feedback," she told BBC News.

"But as with all new technologies, there will be issues that need to be resolved in how it works, which is why it is being trialled before a national rollout."

The NHS is also exploring use of the Apple-Google API, which would entail a switch to the decentralised model.

But it intends to offer users the centralised version first, unless plans to complete the rollout within a fortnight go awry.

Reuters

ReutersOne sticking point could be calls for limits on how the data is used - possibly requiring a new law.

That would avoid the risk of a repeat of the situation in Norway, where the local data protection watchdog has accused the country's health authority of failing to carry out a proper risk assessment of a centralised contact-tracing app.