Coronavirus: State surveillance 'a price worth paying'

A major increase in state surveillance is a "price worth paying" to beat Covid-19, a UK think tank says.

The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI), founded by the former prime minister, says it could offer an "escape route" from the crisis.

In a report, the Institute argues the public must accept a level of intrusion that would normally "be out of the question in liberal democracies".

The rollout of contact-tracing apps has provoked a global debate.

The paper argues all governments must choose one of three undesirable outcomes: an overwhelmed health system, economic shutdown, or increased surveillance.

"Compared to the alternatives, leaning in to the aggressive use of the technology to help stop the spread of Covid-19... is a reasonable proposition," it says.

However, digital rights activists have warned that an overly-intrusive approach could backfire.

"There are many roads for the UK government to choose in lifting the lockdown and determining technology's role within that," said the Open Rights Group earlier this month.

"A collaborative, privacy-preserving model would be best for preserving the trust and confidence of the British public."

'Unprecedented increase'

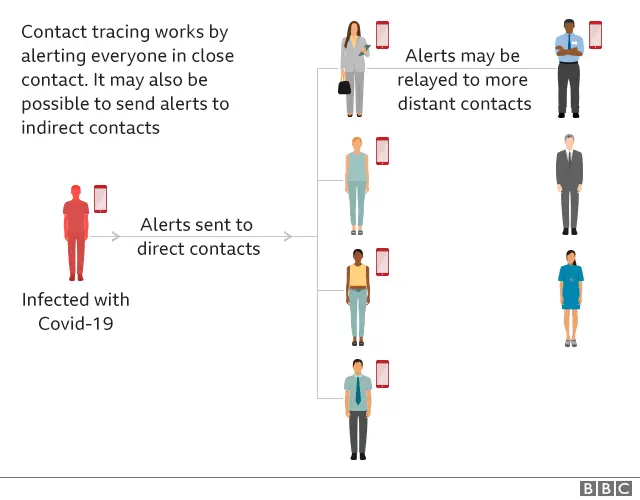

Contact-tracing applications work by logging every person that a smartphone comes in close contact with who also has the app.

If one person is diagnosed with Covid-19, all those at risk can be notified automatically. But experts in the field cannot agree which solution is the most effective while simultaneously protecting privacy rights to the greatest extent possible.

The TBI paper recommends that official contact-tracing apps should be released as soon as possible - but should be opt-in rather than compulsory, in order to boost trust.

It also says there should be a "digital credential" to help lift lockdown restrictions. It would be a type of digital certificate that would identify those who have immunity to the virus and are fit to return to work, though it notes an alternative would be necessary for those without a smartphone.

TBI argues that policymakers must adopt privacy-focused options when all other things are equal, and recommends open and transparent operation.

Among the series of other recommendations and possibilities explored in the report are "cross-referencing" data from healthcare systems and private companies in "real time" and sharing anonymised patient data in the search for a vaccine.

"The price of this escape route is an unprecedented increase in digital surveillance," the report says.

"In normal times, the degree of monitoring and state intervention we are talking about here would be out of the question in liberal democracies. But these are not normal times, and the alternatives are even more unpalatable."

As they try to combat the pandemic, countries around the world are rushing to develop apps and other technology to monitor their citizens' behaviour - often in ways that would have seemed unacceptable just a few months ago.

Faced with interrogation from privacy and data rights campaigners, governments have taken contrasting approaches: Israel collecting masses of data from its mobile networks until protests forced a change of tack, France looking to have some centralised control of data from its contact tracing app, Switzerland going down a much more decentralised privacy-focused route, and the UK, well, still pretty opaque about just how its app will work.

Campaigners are warning that the public will not trust and therefore use apps that don't respect their privacy.

But the public may also look to some Asian countries' success in fighting the virus with some fairly intrusive technology and wonder whether that is a price worth paying to regain another freedom - the right to return to normality.

Surveillance row

The UK is already testing its version of the app at a Royal Air Force Base in England, while France is in a stand-off with Apple over the level of privacy it intends to build into its contact-tracing app.

Germany has now also put itself at odds with Apple, after announcing that its contact-tracing solution would store all the relevant data on a central server, joining France and others in that approach.

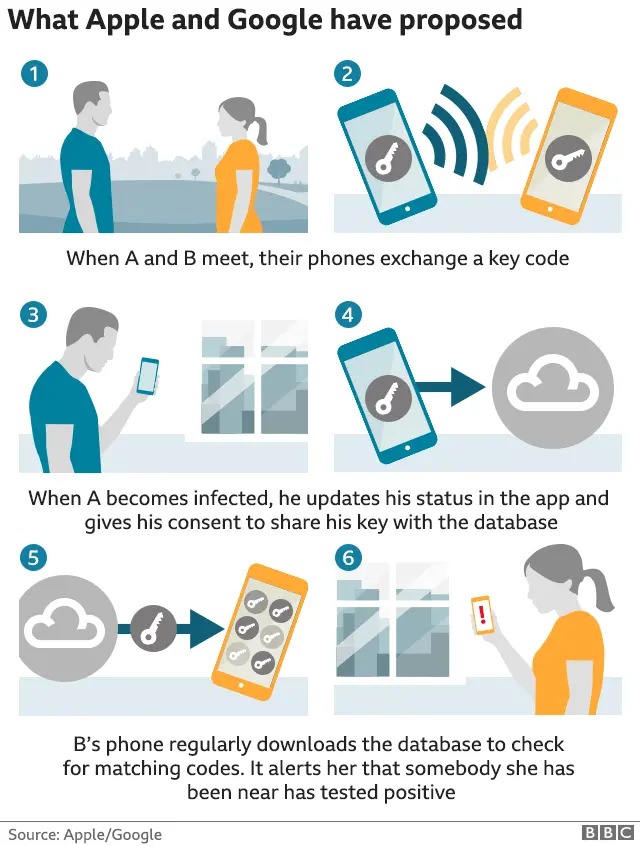

Essentially, Bluetooth "handshakes" between nearby devices are seen as more private than tracking the GPS location of individuals. But Apple does not allow third-party apps to carry out the process in the background, meaning users would have to keep the software running on-screen or repeatedly re-activate it after engaging with other apps for it to prove effective.

The only way to access that functionality is by using the system Apple and Google have decided to co-develop. But that would involve doing the contact-matching on a person's smartphone, rather than in a central location, which is what several countries want.

The German option is backed by the Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT) group - which aims to create a platform that would work across borders. But it is facing its own problems, with several senior figures objecting to its plans and splitting off to campaign for the use of a protocol called Decentralised Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (DP-3T).

DP-3T is being used by Switzerland and Austria, and is also reportedly set to be adopted by Estonia, leading to a divided approach cross Europe.