Amazon's Ring logs every doorbell press and app action

Amazon

AmazonAmazon keeps records of every motion detected by its Ring doorbells, as well as the exact time they are logged down to the millisecond.

The details were revealed via a data request submitted by the BBC.

It also disclosed that every interaction with Ring's app is also stored, including the model of phone or tablet and mobile network used.

One expert said it gave Amazon the potential for even broader insight into its customers' lives.

"What's most interesting is not just the data itself, but all the patterns and insights that can be learned from it," commented independent privacy expert Frederike Kaltheuner.

"Knowing when someone rings your door, how often, and for how long, can indicate when someone is at home.

"If nobody ever rang your door, that would probably say something about your social life as well."

She added that it remained unclear how much further "anonymised" data was also being collected.

"This isn't just about privacy, but about the power and monetary value that is attached to this data."

Amazon says it uses the information to evaluate, manage and improve its products and services.

Motions and 'dings'

The BBC originally made the data subject access request (DSAR) in January to tie into a wider investigation into the ways Amazon gathers and uses information about its customers.

At that point, the firm declined to elaborate on what information was collected beyond its privacy notice's mentions of "data about your interactions", "device characteristics" and other such inexact terms.

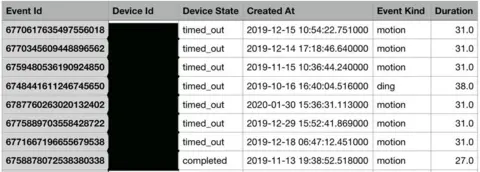

The records ultimately provided ran from 28 September 2019 until 3 February 2020. A Ring 2 Video Doorbell was in use over all this time, and a Ring Indoor Cam was added to the account over the final fortnight.

Over the period, there were 1,939 individual "camera events" documented.

These included:

- a motion being detected by the cameras' sensors

- a "ding" of the doorbell, when its button had been pressed by a visitor

- a remote "on-demand" action by the user to get a live video and audio feed and/or remotely speak to a visitor

In each case, the length of time the equipment was activated was also logged.

Ring says its cameras use face and body-shape analysis to help differentiate between humans and other living things in order to minimise false alarms. However, there was no indication of different types of motion being detected in the shared data.

Camera co-ordinates

The largest database provided documented every interaction with Ring's apps.

It listed 4,906 actions over the 129-day period.

These included:

- every time the app was opened

- whenever the user "zoomed in" via a finger-pinch to view the footage more clearly

- a variety of different-classed screen taps

- details of the start and end to each live-view

In each case, the model of device used, the version of its operating system, the type of mobile data-connection involved and network supplier were all listed.

Among other records were the details of the latitude and longitude co-ordinates of the two devices, provided to 13 decimal places. In theory, this would pinpoint where the products had been installed to the nearest 0.00001mm.

When checked via an online tool, the readings corresponded to the right property.

However, since the same co-ordinates were given for both devices - which were based in different parts of the building - it appears that Amazon does not know the products' locations to this degree of precision.

'Tip of the iceberg'

In total, 11 databases were shared containing close to 26,500 individual fields.

Ring's privacy notice indicates that other data is also collected for analysis, which is anonymised so that it cannot be linked back to individual accounts.

Amazon

Amazon"Data access requests only ever show us the tip of the iceberg of the amount of data that companies collect about us," commented Ms Kaltheuner.

"There's huge value - and power - in collecting non-personal data for all sorts of purposes: market research, training and AI.

"Even anonymous data can have privacy implications, for instance about the collective privacy of, say, a housing block, a group of people, or a household unit."

No video files were included in the DSAR response.

Ring justified the omission on the basis that its app already makes it possible to download the clips for up to 30 days if the user had a paid subscription. After that time, the company said each recording was permanently deleted. It added that if a user did not subscribe to a plan then Ring did not keep any recordings.

Amazon's retail operation and its Ring subsidiary operate under different data controllers.

The BBC asked if the two might ever make their records available to each other to make it possible to make joint use of the information - for example, using Ring's data to see when a family was typically at home in order to help schedule package deliveries.

However, the firm declined to respond.