How an asparagus farmer's death spurred robotic innovation

It seems there are few jobs robots can't do these days, even the most delicate jobs, like picking asparagus or potting plant seedlings. But they're only needed because humans can't - or won't - do the work, farmers say.

Marc Vermeer had a problem. He was struggling to attract workers to pick his white asparagus crop in the Netherlands.

The workers he did hire moved on quickly, so he was always training new people.

White asparagus needs to be picked at a particular moment while it is still under the ground, otherwise it turns green.

It is often difficult to detect and can be damaged easily.

So in 2000, fed up with his situation, Marc challenged his inventor brother Ad to make a robot to replace human workers.

Therese van Vinken

Therese van VinkenAd had been designing intricate machines for decades in the semi-conductor industry. They came up with some ideas to try, but nothing worked.

Fourteen years later and facing increasing labour problems, Marc insisted that Ad should now be able to come up with a machine that could "see" deep into the ground to pluck out the asparagus as well as a human.

This time Ad saw a way forward using new technology.

"Selective harvesting is really complex, you need hi-tech sensors, you need electronics, you need robotics," he says.

"But these complex hi-tech machines get more and more feasible to develop because technology is improving."

Along with Ad's wife, Therese van Vinken, an expert on securing financial funding, they founded robotic start-up Cerescon.

"Marc knew the asparagus farmers and he had experience with sales," Ms van Vinken says.

"The deal was Marc does the commercial part, Ad does the development, and Therese takes care of the money."

But the day after celebrating the company's legal incorporation on 11 December 2014, tragedy struck.

Marc, a 51-year-old father of three, suddenly became ill with meningitis. He was placed in an artificial coma for several days.

"One of the first things that his wife Anita said to us was that when Marc was out of the coma he was constantly talking about that machine," Ms van Vinken says.

But Marc never lived to see the robot working in his field. He suffered a cerebral haemorrhage after leaving intensive care and died within 10 minutes.

Cerescon

CeresconIn shock, and with no idea about the farming side of the business, Therese and Ad thought about giving up.

"Especially in the beginning there were many moments I thought: well forget it, no way," Ms van Vinken says.

But with hundreds of thousands of euros in subsidies already spent, they knew they had to push forward.

Today, they have sold their first commercial machine to a farmer in France. The three-row version can replace 70 to 80 human pickers.

"It's the first selective harvesting machine ever on the market," says Ad Vermeer.

"I'm sure it's going to be the first one of a new kind, and there's going to be lots of different selective harvesting machines in the future."

To "see" the asparagus, the robot injects an electrical signal into the ground. Sensors dig through the soil and pick up the signal the closer they get to the asparagus.

"The asparagus is actually conducting the signal electrically because there is a lot of water in there," he says.

"Basically, the difference between the water content of the asparagus and the sand, that makes the difference to how we detect the asparagus."

Cerescon's robot is one of many machines being developed around the world to replace delicate farming jobs.

"Over the years, we have seen many tasks become feasible to be taken over by robots," says Rick van de Zedde of Wageningen University in the Netherlands, where teams are researching autonomous solutions for jobs up and down the fruit and vegetable supply chain.

"If you look at the way the current agri-food production is developing there is a scarcity of labour, but also a lack of motivated or skilled people," says Mr van de Zedde.

The problem is that many of the jobs are "repetitive and pretty dull", he says, but still require deft handling when dealing with fragile seedlings and flowers.

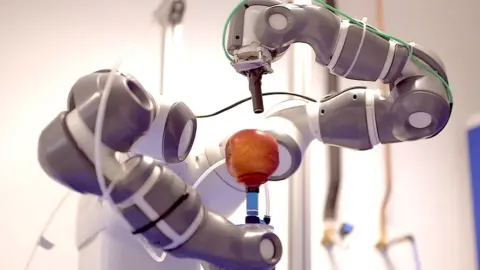

But even here, robots are learning to adopt a gentle touch.

The factory floor at Florensis, one of the Netherlands' largest flower suppliers, is whirring with the sound of robots hard at work.

Sticking cuttings into tiny soil pots needs to be done very gently, and is traditionally humans' work.

Indeed, there is a line of tables manned by humans, but there are also six autonomous machines on the other side of the warehouse.

These machines can plant up to 2,600 cuttings an hour. A skilled human can manage 1,400 to 2,000. And the machine does not tire, rarely breaks down, and plants the cuttings to the same depth every time.

"Due to the fact there is a lack of labour it forces us to look for alternatives that will enforce development," says Marck Strik, director of product development at Florensis.

The robot works out which end of the cutting is a leaf and which is a stem with the help of image-recognition cameras, and will even shake the conveyor belt to get a better look.

More Technology of Business

Magnum Photos

Magnum Photos"Everybody has been searching for this breakthrough in the industry and we feel that this is one of those breakthroughs that really has an exponential possibility," says Mr Strik.

"At the end of the game, you can work 24 hours a day and save, let's say, 60% of your labour costs," he says.

"I believe - and I am convinced - that this is just the start and absolutely this will replace the human being."

- Click here for more Technology of Business features

- Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter and Facebook