YouTube and Instagram face Russian bans

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYouTube and Instagram face being blocked by Russian internet service providers as a result of a standoff between one of the country's richest businessmen and an opposition leader.

Russia's internet censor blacklisted material on both services after a court ruled that it violated billionaire Oleg Deripaska's privacy rights.

However, Alexei Navalny has refused to remove the videos and photos, which he claims are evidence of corruption.

A Wednesday deadline has been set.

If neither Mr Navalny nor the US tech firms involved delete or otherwise block local access to the imagery by the end of the day, then Russia's ISPs will be required to take action themselves.

A group representing the industry has indicated that this could result in all local access to the social networks being curtailed since ISPs lack the facility to censor specific posts.

"It's impossible for internet providers to block certain pages on Instagram and YouTube," a spokeswoman for the Russian Association for Electronic Communications told the BBC.

Mr Navalny is Russia's most prominent opposition leader. But he has been barred from standing against President Putin in next month's election because of a corruption conviction, which he says is politically motivated.

Shared video

Mr Navalny's Anti-corruption Foundation posted a video to YouTube last Thursday in which he presented footage that allegedly showed Mr Deripaska meeting Russia's deputy prime minister Sergei Prikhodko aboard a yacht.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe material was said to have been sourced from a woman's Instagram account, where it had been posted in 2016.

Mr Navalny also uploaded a photo of the "secret meeting" alongside a post detailing corruption claims, to his own Instagram account.

The next day, Mr Deripaska obtained a court order demanding the removal of 14 Instagram posts and seven YouTube clips.

And on Saturday, the government's internet watchdog Roskomnadzor issued the two tech platforms a take-down notice giving them three business days to comply.

Google subsequently wrote to Mr Navalny's team saying it might be forced to block the videos.

But to date, neither it nor Facebook has censored the material.

The two firms have yet to publicly comment on the matter.

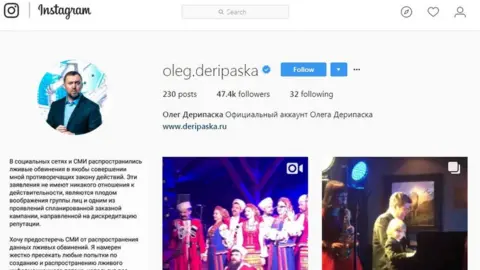

Instagram

InstagramFacebook is already facing an audit by Roskomnadzor of its compliance with Russian laws, a move that was also announced last week.

Human rights

Mr Deripaska has threatened to sue those who repeat Mr Navalny's claims.

"I want to warn the media against the dissemination of these mendacious accusations," he said in a statement published by the Washington Post last week.

"I will severely suppress any attempts to create and disseminate false information flow using all legal measures and will defend my honour and dignity in court."

One Moscow-based campaigner said the dispute formed part of a wider effort to censor the net.

Reuters

Reuters"In recent years, Russian authorities have stepped-up measures aimed at bringing the internet under greater state control," said Tanya Lokshina from Human Rights Watch.

"The government pushed through the parliament a raft of new restrictive laws and is using different pretexts and mechanisms to block critical websites and web pages and silence critical voices online.

"Facebook, Google and other major internet companies operating in Russia should carefully assess demands to censor content or share user data and refrain from complying where the underlying law or specific request are inconsistent with international human rights standards."

Analysis

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy Sarah Rainsford, BBC Moscow Correspondent

Compared to Russian television, which is under tight central control, the internet is still a relatively free space.

Alexei Navalny uses YouTube to post his anti-corruption videos and to livestream protests.

During the 2011-12 elections, videos of ballot-stuffing posted online sparked mass protests. Twitter, Facebook and other platforms are hugely popular.

But restrictions on online activity and even prosecutions have been increasing. The blacklist maintained by watchdog Roskomnadzor includes a support group for young LGBT people and the Jehovah's Witnesses - banned in Russia as "extremist".

The human rights group Agora highlighted an increase in censorship in its latest report, finding that last year more than 240 pages were blocked on average every day.

Meanwhile, prosecution even for "liking" or sharing posts on social media is increasingly common.

Most recently, several people reposting information about January's protests in support of Navalny were sentenced to police custody as the rallies had not been sanctioned by the authorities.

Blocking Instagram and YouTube might placate an oligarch. It would likely complicate life for opposition groups and activists. But it would certainly upset millions of other Russian internet users.

Just ahead of an election that Vladimir Putin wants to win with a resounding majority, that seems like a risky step to take.