Apple's Tim Cook keeps nephew off social media

Getty Images

Getty ImagesApple chief executive Tim Cook has said he does not want his nephew to be on a social network.

His comments come as a survey suggests the wider British public is becoming increasingly distrustful of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

The platforms have all acknowledged problems in recent days.

One expert suggested technology companies should face tougher regulations despite their efforts to resist the prospect.

Age limits

At a coding-related event at Harlow college, in Essex, Mr Cook told a Guardian reporter: "I don't have a kid, but I have a nephew that I put some boundaries on.

"There are some things that I won't allow. I don't want them on a social network."

Mr Cook did not disclose the age of his nephew, but in an interview in March 2015 he mentioned he was 10 years old at the time.

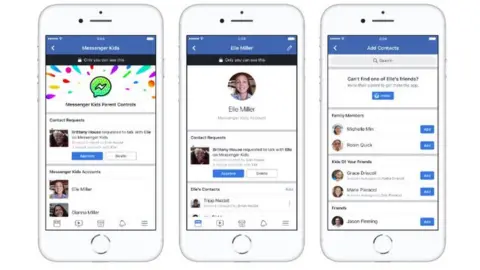

The US's Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (Coppa) places restrictions on the information technology companies can collect about under-13s, and many social media companies officially bar younger users from their services as a consequence.

Facebook

FacebookBut last November, the UK communications regulator, Ofcom, reported under-age use of social media was on the rise, prompting the charity the NSPCC charity to accuse Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat of "turning a blind eye" to the problem.

Propaganda campaigns

Social networks have faced a barrage of other criticism in the ensuing months.

One issue has been the degree to which they have allowed their platforms to be manipulated by "fake news" and propaganda.

On Friday, Twitter acknowledged that more Russia-linked accounts had been engaged in efforts to spread discontent on its platform during 2016's US presidential election than it had previously acknowledged.

As a result, it said it was emailing 677,775 US-based users to alert them to the fact they had followed at least one of the suspect accounts or "liked" or retweeted their posts during the election period.

Elsewhere, two Facebook executives have acknowledged issues with their service.

"We have over-invested in building new experiences and under-invested in preventing abuses," public policy chief Elliot Schrage told the DLD Munich conference on Sunday, echoing a mea culpa by the company's chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, at the start of the year.

Facebook's civic engagement product manager, Samidh Chakrabarti, has also blogged that social media companies in general need to be more aware about the influence they wield.

"If there's one fundamental truth about social media's impact on democracy, it's that it amplifies human intent - both good and bad," he wrote.

"At its best, it allows us to express ourselves and take action. At its worst, it allows people to spread misinformation and corrode democracy.

"I wish I could guarantee that the positives are destined to outweigh the negatives, but I can't. That's why we have a moral duty to understand how these technologies are being used."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMeanwhile, YouTube has been more concerned with mopping up the fallout from a vlogger who posted footage of an apparent suicide victim in Japan.

Logan Paul's video led the creator to be thrown off the platform's premium advertising service and prompted last week's decision to carry out human reviews of other featured clips.

But YouTube's chief business officer, Robert Kyncl, has now told BBC Newsbeat that he does not believe that the service should be regulated by third parties.

"We're not content creators; we're a platform that distributes the content," he said.

New rules

Social media companies - and Apple itself - also face growing criticism that their products are addictive in nature.

The recently created Time Well Spent campaign group says: "What's best for capturing our attention isn't best for our wellbeing," adding the platforms would not change unless made to do so.

Several technology leaders - including Facebook's chief operating officer, Sheryl Sandberg, and Google's chief executive, Sundar Pichai, - are expected to resist calls for further regulation at behind-the-scenes meetings at the World Economic Forum in Davos this week.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut one industry watcher thought it likely that legislators and their watchdogs would soon intervene in the way technology companies operated.

"They are having huge effect on the ways we get information and how we live our lives," said Dr Joss Wright, from the Oxford Internet Institute.

"And the idea that because they are 'technology' means they should be exempt from regulation or should be allowed to fix all the problems themselves doesn't stand up.

"We need to have a say as society in what their problems are and what effects they are having, and that's the role of regulation."