Virgin's Hyperloop: Future or fantasy?

So, here's the plan - we're going to load you into a pod, and then shoot you at 700 mph (1,123 km/h) through a vacuum, taking you to your destination in minutes rather than hours.

That is the rather unlikely pitch of Hyperloop One.

But the remarkable thing that struck me on a recent trip to the project's test site in Nevada was that nobody thought it was, well, remarkable.

The Hyperloop idea, first floated by Tesla's Elon Musk, has sparked a number of projects keen to demonstrate that putting a maglev train in a vacuum tube can deliver the revolutionary transport system of the future.

Maglev - or magnetic levitation - trains, which use magnets to lift a train above rails, reducing friction and increasing possible speeds, are already in operation. One takes passengers from Shanghai to its airport at 270 mph (430 km/h).

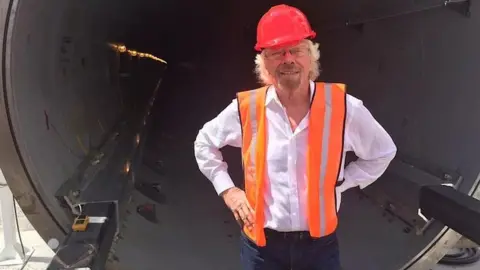

But of the plans to make a maglev even faster by putting it in a vacuum tube, Hyperloop One - or as we must now call it following Sir Richard Branson's investment, Virgin Hyperloop One - is the most advanced.

Arriving on the site in the desert 40 miles north of Las Vegas, you can immediately see this is a costly operation to run.

A 500m (1,640ft) test track, or Devloop, has been constructed and a workforce of 300, including 200 high-calibre engineers, has been assembled.

They have run a number of tests, propelling a pod through the tube at speeds of up 387km/h (240mph).

So far, however, they have not put people on board.

Leading the engineering team is a fast-talking space scientist Anita Sengupta, recruited from Nasa where she helped develop the Mars Curiosity rover.

Having worked on what she describes as the "challenging engineering problem" of landing vehicles on other planets, she brushes aside my doubts about whether this earthbound project is realistic.

She gestures towards the white pipe snaking across the desert: "It's a realistic project because you can look around and see our development test tube."

She says the technology has already been proven and dismisses my suggestion that people might be cautious about climbing aboard.

Virgin Hyperloop One

Virgin Hyperloop One"The Hyperloop is a maglev train in a vacuum tube," she explains.

"You can also think of it as an aircraft flying at 200,000ft [38 miles]," she added referring to the equivalent air pressure level.

"People don't have any issue flying in aircraft and people don't have any issue travelling in maglev trains. This just combines the two."

She predicts that the project will have passed through safety certification and be ready to launch a commercial operation by 2021, which seems insanely optimistic.

It is the job of the chief executive Rob Lloyd to sell the Hyperloop to the commercial and government partners who will make it a reality.

But when we met him at the giant CES tech show in Las Vegas, he appeared to think that the viability of the technology was a given, wanting to talk instead about an app that would connect future Hyperloop passengers with other modes of transport on arrival.

Virgin

VirginI tried to bring him back to earth by explaining how long it took to build infrastructure projects like Britain's HS2 high-speed rail line from London to Birmingham.

He came straight back with an idea he said could mean that the third runway at Heathrow - another project that has been many years in the works - would no longer be needed.

"You could build a Hyperloop between Gatwick and Heathrow and move between those two airports as if they were terminals in four minutes," he explained.

"That's probably less time than it takes to move between Terminal 5 and Terminal 2 today at Heathrow."

Creating one giant seven-terminal airport without the huge cost and controversy of building a new runway might seem attractive. Sir Richard Branson, who now chairs the project, told us "a fast link between Heathrow and Gatwick would make a lot of sense". But it also sounds fanciful.

The cost of tunnelling from Heathrow to Gatwick or the planning nightmare of running several tubes across the Sussex and Surrey countryside would surely make building a third runway seem like a piece of cake.

Meanwhile Elon Musk is pursuing his own Hyperloop projects, tunnelling under Los Angeles and claiming last summer that he had "verbal approval" from the US government to build a link that would take passengers between New York and Washington DC in under half an hour.

This also sounds a deeply unlikely mission, and one suspects that the investors who have poured so much money into Musk's Tesla would be reluctant to open their pockets again.

But Rob Lloyd at the Virgin Hyperloop remains confident that at least a few governments will have the vision to take forward what he calls the first new mode of transport since the aircraft.

After years when technology innovation seems to have been all about social media - 140 characters instead of jetpacks as investor Peter Thiel puts it - such an ambitious vision is refreshing.

Even if one suspects that Hyperloop routes linking major cities are unlikely to make it off the drawing board, the project is doing a great job of making us think about a greener transport system.