Long Covid: 'My fatigue was like nothing I've experienced before'

BBC

BBC

Thousands of coronavirus patients, including many who were not ill enough to be hospitalised, have been suffering for months from fatigue and a range of other symptoms. While professionals struggle to support them, what can they learn from those living with chronic illnesses?

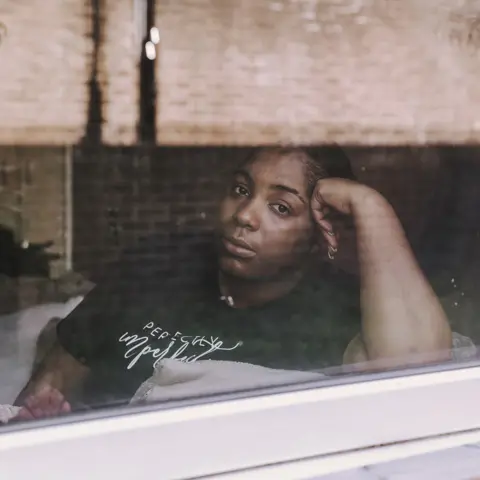

If you've been following the stories of people who have contracted coronavirus and are experiencing debilitating symptoms that won't go away, Jade Gray-Christie's story may sound familiar. Because her symptoms were considered "mild", she was not hospitalised, but her life has been turned upside down since falling ill in March.

Before the pandemic, Jade had been living an extremely busy life. The 32-year-old from Stoke Newington in London was balancing a fulfilling job supporting young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, with an active social life, and going to the gym three times a week.

But in the early hours of the morning on 15 March, Jade came home from a long day at work, and knew something wasn't right.

"I felt horrendous. I was starting to feel really hot and cold and I just kept coughing and coughing and coughing," Jade told me, speaking softly, through laboured breaths.

As the days went by, Jade, who is asthmatic and lives alone, started to feel more and more unwell and scared.

She called 111. They sent an ambulance to her ground-floor flat, but the paramedics refused to come in.

"They spoke to me through the window and asked what was going on," she says.

BBC

BBCLying in bed and struggling to get the words out, Jade explained that she was finding it hard to breathe and had severe pains in her chest. She was told that she had the classic "Covid cough", but because of her age, they couldn't take her to the hospital. She was young, they said, and her body was strong enough to recover.

Jade was taken aback. "What do I do about my breathing? I'm asthmatic. I live by myself so if something happens I've got nobody to support me. What do I do?"

But she was told that they weren't taking anyone under the age of 70 in case she made someone else in the hospital ill.

"So I was kind of just left," Jade says. "I understood what they were saying, but at the same time I was really poorly and I didn't know what would happen. I was quite scared to go to sleep at night."

Jade started leaving her front door unlocked, asking her neighbours to check on her daily to make sure that nothing happened to her as she slept.

As time went by, she did seem to slowly improve. But every time she thought she was making a recovery, her symptoms returned.

In May, Jade felt well enough to start working part-time from home. She was still experiencing chest pains and some tiredness, but as someone who was used to a busy life, she felt she could manage.

Then, at the end of the month, something changed.

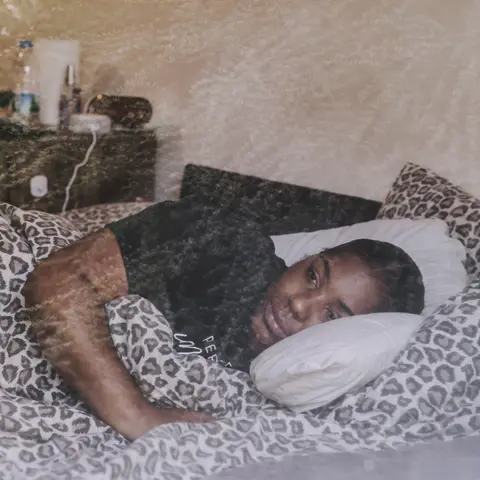

"My chest got really bad again. I was struggling to breathe and I wasn't able to get out of my bed," she says. "My fatigue was like nothing I've ever experienced before."

BBC

BBCMonths passed with little improvement. Sometimes she slept more than 16 hours per day, and struggled with the day-to-day activities needed to look after herself.

When I checked in on Jade at the end of July, she told me that her doctor said she had post-viral fatigue - but she hadn't been given any advice on how to manage her symptoms beyond being told to "pace" and have a routine for sleeping and waking.

Pacing is a skill that involves breaking challenging elements of your life into smaller, more manageable ones. The idea is to learn coping strategies to help improve quality of life and stabilise your health.

But Jade struggled to understand how to apply the idea of pacing to her life. Keeping to a routine felt almost impossible, as she often woke up exhausted and just fell back to sleep again.

"When I did speak with the doctor regarding my dizziness, the fact I have fainted, and also about my fatigue, he openly stated that he did not know how to support me and that the virus is still so new. This of course left me feeling even worse."

"If the doctors cannot help, then who else can?" she asked.

The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges that it does not yet fully understand Covid-19.

It says that typical recovery times are two weeks for patients with mild illness, and up to eight weeks for those with severe illness, but it recognises that there are people like Jade who continue to have symptoms for longer.

In such cases, the WHO says, symptoms may include extreme fatigue, persistent cough or exercise intolerance. The virus can cause inflammation in the lungs, cardiovascular and neurological systems, and it can take a long time for the body to recover.

Jade's experience has been echoed by tens of thousands of people across the country, and is now known as "Long Covid".

According to the Covid Symptom Study app, which tracks people's symptoms regardless of whether they had a test, about 300,000 people in the UK have reported symptoms lasting for more than a month, and 60,000 people have been ill for more than three months.

Barbara Melville is an admin of the Long Covid Support Group on Facebook, which was set up to provide a place for people to talk about their experiences and support each other. It now has over 21,000 members, who are living with a wide range of symptoms.

Interestingly, a lot of people in the group, like Jade, originally had a mild case of coronavirus, though one doctor described Barbara's as "moderately severe".

BBC

BBCMany of them say they are not able to access the care and support they need, and she describes "two emerging narratives" when it comes to trying to find help.

Some struggle to be taken seriously at all, with people being told, especially early on, that their symptoms are caused by anxiety, she says.

Others have sympathetic GPs who will arrange blood tests and chest X-rays or CT scans for lung issues - but once those examinations have been carried out, they are not sure what specialist services to refer them to, or how to help them.

"I think most GPs are at an absolute loss, they don't know what to do for people," Barbara says. "It's about policy. Doctors don't have the guidelines yet to know what to do, so everybody is shooting in the dark."

During the early months of the pandemic, when there was even less help or recognition for people experiencing Long Covid symptoms, many patients and patient advocacy groups started doing their own research.

"You don't know if you're going to live or die, and Covid puts you on a merry-go-round of symptoms - one minute it's pain in kidneys, then stomach. For a lot of people, although not for me, there's also lung issues and shortness of breath," says Lorraine Pickering, a former teacher at a busy secondary school in Wiltshire, who developed symptoms in March and has since been diagnosed with Covid.

Looking for answers, she turned to the chronic illness community and realised that many of their symptoms overlapped. She found a huge amount of useful advice and support about how to cope with a long-term health condition - learning that with the right adjustments it was still possible to have a fulfilling life.

"If you've never been ill before, it takes a lot of emotional and physical resilience," she says.

She also noticed that early on in the pandemic, people living with chronic illness were already speculating about the potential long-term repercussions of coronavirus, and were concerned for this new influx of patients.

There was a palpable fear that some people wouldn't make a full recovery, and also that this would strain a system where many already struggle to get the care and support that they need.

"The chronic illness community is used to waiting 12 months to see a specialist or spending three hours in a clinic waiting for a 10-minute test, but this may well come as an unpleasant shock to previously healthy folks," says Jo Southall, an occupational therapist who specialises in supporting people with chronic illness.

"There were a whole lot of people on waiting lists for rehabilitative care before Covid-19 hit and the backlog has only got worse."

Lauren Walker, an adviser to the Royal College of Occupational Therapists, adds that access to specialists has always been a "postcode lottery" and that it is a particular problem for disadvantaged groups. "It is a really inequitable system," she says.

Find out more

- Listen to Jade Gray-Christie and Jo Southall on the Ouch! podcast: It is possible to be tired and in pain and happy at the same time

- Download more Ouch! Cabin Fever podcasts here

In an attempt to help the growing number of people with long Covid symptoms, in July the NHS launched an online portal called YourCovidRecovery.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said it would "give people who have survived the virus on-demand access to online clinical support" for problems with breathing, mental health or other complications.

However, Barbara says the response from her support group has been mixed, with some pointing out that it simply duplicates advice about pacing and breathing exercises that is already available elsewhere online.

"Sufferers are looking for comprehensive support, such as time with specialist consultants. They don't need more of the same," she says. But, in many cases, these are the same specialists that there are already long waiting lists to see.

Jo Southall has a more positive view of the portal.

"Good quality generic advice is essential in the 'waiting' stages," she says.

She believes that the most important thing at the moment is to prevent people from getting worse, and one danger she sees is that people could be encouraged to exercise too hard - which could make them more unwell.

In July, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cautioned against using graded exercise therapy for patients recovering from Coronavirus. (It also noted that its advice for managing chronic fatigue could be out of date for other groups of patients too. This advice is currently under review.)

"Sometimes no progress is progress," Jo says. "It's all too easy for health to spiral downwards with symptoms like fatigue, so when you're going it alone, a plateau should be seen as a win."

How to conserve energy

- When dealing with fatigue, occupational therapists use something called the three P's: planning, pacing and prioritising

- This involves identifying strategies to make things easier and manage energy more effectively

- For example, if showering is exhausting, try it at a different time of day, or sit down instead of standing

- Break activities up into smaller tasks and spread them throughout the day

- Plan 30-40 minutes of rest breaks between activities

Lauren Walker, Royal College of Occupational Therapists

So, where does this leave patients? For many, it's still a waiting game.

BBC

BBCAs for Jade, her health is still up and down, but she is now getting physiotherapy and occupational therapy through the Covid clinic at University College Hospital in London.

Her employers have been very supportive, which has made a huge difference. When she had an occupational assessment, she was told that they had seen many similar cases.

"That was a huge relief, just to be believed," she says, having spent many months feeling as though she had to prove that what was happening to her was not "all in her head". She finally received a letter confirming her Covid diagnosis this week.

Jade is now planning to work from home for the rest of the year, with reduced hours and responsibilities, and has been advised to break up her day, working in two-hour stints with mini-breaks in between. She's glad to be able to get back to work and engage her brain.

BBC

BBCNot all employers are as sympathetic, warns Barbara, with many stories being shared in her support group of people forced back to work too soon.

"They're scared that they're not going to be able to feed their families," she told me. "Rest and pacing are a privilege."

Others have told her they're facing discrimination at work because they are unable to provide evidence that they had the illness - even though testing wasn't made widely available for months - and are not being given the adjustments they need to work safely.

She is, however, hopeful that this crisis will lead to a culture change in the way people living with long-term health conditions are treated.

"What I'd like to see in five years' time is that someone with Long Covid symptoms, or any illness, can go to the doctor, get the support they need, for the doctor to feel supported, and that people feel able to talk about this with their employers and peers.

"Covid has really highlighted inequalities and there's an opportunity here to start doing something."

In one of our calls, Jade told me that after becoming ill she really felt like her life was over. It was only once she started getting support, care and understanding that things started to change for her. She now feels like she may be able to find a way to cope with her new normal.

Photography by Zoë Savitz

You may also be interested in:

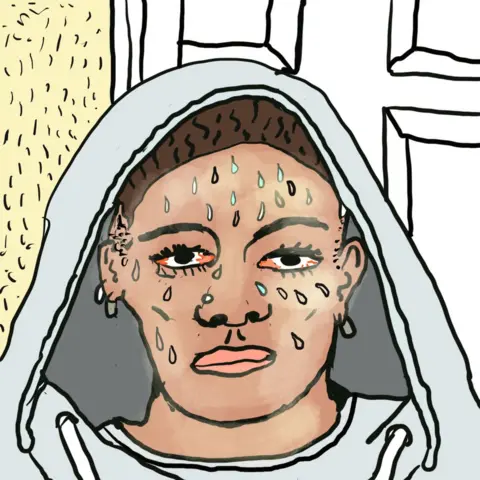

Monique Jackson

Monique JacksonMonique Jackson believes she caught Covid-19 early in the pandemic and nearly six months later she's still unwell. One of thousands in this position, she has been keeping an illustrated diary about her symptoms and her vain attempts to get treatment.