‘We were students negotiating with armed guerrillas for my father’s life’

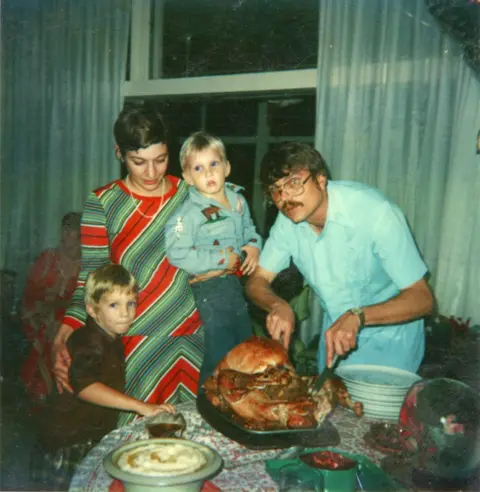

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveWhen Miles Hargrove's father Tom was taken hostage by armed guerrillas in Colombia, he put his trust in a 22-year-old friend to negotiate with the kidnappers and help bring his father home. Could these innocent young students possibly succeed?

Beep…

Beep…

Miles Hargrove's answering machine was frantically flashing.

"Miles, this is your mum, we've got a little problem and you need to call your uncle Raford."

This was just the first of nine messages, something was clearly wrong.

"I knew it was really serious," says Miles, "because the following messages were from my uncle saying, 'Miles there's a problem, give me a call.' So by this point I'm like, 'Oh my God what's happened?'"

It was September 1994 and 21-year-old Miles was in his student dormitory at university in Texas. He feared bad news. Could someone have been involved in a car crash?

What his uncle told him knocked the wind out of him: "Your dad was on his way to work this morning and he was kidnapped."

Miles's parents, Tom and Susan Hargrove, were living in Cali, a city in the south-west of Colombia. The family had moved there a few years earlier for Tom's work as a humanitarian agricultural specialist, and Miles and his brother had finished school there. But it was becoming an increasingly uncomfortable place to be.

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveThe Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), an armed guerrilla group, were at war with the Colombian government, and one way they raised money was by kidnapping people and ransoming them. This had started occurring more frequently in the Cali region and Susan had had a premonition that something bad was going to happen. She'd already asked Tom to look for a new job.

And now Tom had been taken.

"His car had been found by the side of the road where there had been this road block. His ID and some pamphlets left by Farc were on the front seat," says Miles.

"The guerrillas were conducting what's called a 'miracle fishing' operation. They basically would set up these roadblocks looking for cars or cash - just anything that could get them a little bit of money for their cause. But when this American was there all of a sudden, that's where the big money was."

Witnesses said they put Tom in the back of one of the pick-up trucks they'd just stolen and headed off east into the Andes mountains.

Miles flew to Colombia to be with his mother. His younger brother Geddie, who had been studying in Egypt, joined the family too.

"It was scary because we'd been told that they would probably be looking, trying to find out anything they could about the family to see who they're dealing with," says Miles. "So there was this feeling of being watched. None of us wanted to leave our little compound."

Miles says his mum remained strong and in control of her emotions, but underneath the surface the family was panicking. "There was a strong sense of adrenaline that was flowing through all of us."

Find out more

- Miles Hargrove spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service (producer Fiona Woods)

- Download the podcast for more extraordinary stories

Fortunately there were other people around who had been through the same thing before.

"They all of a sudden came out of the woodwork and started talking us through it and saying, 'Just negotiate with them, you're going to have to pay a ransom, this is going to take time, but just co-operate and that's how you're going to get it resolved.'"

The family had been warned they could expect to wait at least three weeks or a month to hear anything from Tom's kidnappers. They waited and then waited some more.

On day 21 it arrived - a "proof of life" video.

Tom was pictured in the grainy footage surrounded by masked soldiers holding guns. It was a shocking image, but Miles says it was also a relief to see him and know that he was alive.

"The worst part for me was watching my mum watch the footage," he says. "I just remember her touching my dad's face on the screen."

The kidnappers demanded the impossible - the family would have to pay $6m (£4.6m) to get Tom back - and they said they would only negotiate with the family or a friend of the family.

"Everybody told us that a rescue was not what we wanted to do," says Miles. "Farc controlled a large territory in Colombia at the time. They controlled the highlands, and trying to send some military unit into that area to get my father released, the chances of him surviving something like that were slim to none."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe negotiator would have to speak fluent Spanish, understand the local dialect and, most importantly, be someone the family could absolutely trust.

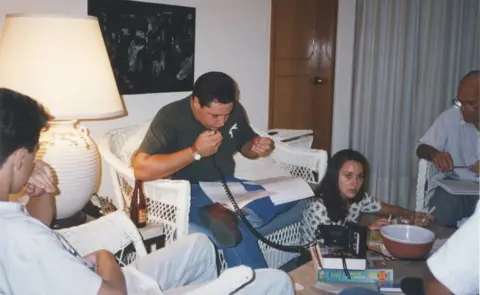

None of them could take on the role themselves because they weren't fluent enough in Spanish, so they turned instead to a Colombian friend of Miles's, Robert Clerx. Miles and Robert had met on Miles's first day at high school in Colombia and they had been close friends ever since. Like Miles, Robert was now a student. He was only 22.

Everything had to be kept secret.

"You cannot have a third party knowing you're negotiating, you're offering this, you're offering that, you're getting proof of life, no - everything has to be kept in a tight circle," says Robert.

They also received advice and instructions from a UK expert in negotiations, who told them to be calm, to talk slowly, and follow a script.

"Before each communication," says Robert, "we basically had a script of what we were going to say, what we were going to ask, and the idea was not to deviate from that script."

The kidnappers spoke in code, so Tom became "the building" and they would state how many "barrels" (how much money) they would be willing to pay for this "building".

At the first negotiation, Team Tom gathered round the shortwave radio used for communication, and Miles heard for the first time the chilling voice of one of his father's kidnappers. The family had decided on a risky strategy - to offer $41,000 (£31,000) to demonstrate to Farc that $6m was a completely unattainable figure.

Miles Hargrove

Miles Hargrove"The risk of making them angry is always there," says Miles. "That's what the advisers explained to us and to Robert, because Robert was the one that was having to deal directly with them. They're going to make these threats, they're going to tell you the most horrible things. At the end of the day it's a business, Tom's a commodity, if the hostages harmed or killed him, then they don't make any money and they've wasted a lot of time and resources."

The offer did enrage the kidnappers.

"With that money you won't even get the body," they told Robert.

But the negotiations continued, twice a week, usually at 7pm.

"I remember on one occasion I had an exam," says Robert. "There were some delays in the computer room in the university, I literally had to step out of the exam and say, 'Teacher, I'm sorry, I have to leave.' I probably was like the rudest brat in the class, because I just stepped out, but I mean I couldn't tell them, 'Look, I'm negotiating a kidnapping.'"

As the talks continued, the Hargroves' neighbours, the Greiner family, constantly encouraged them to try to live as normal a life as possible.

"Claudia Greiner made a real push for us to try and really make an effort for dinners at night," says Miles. "She had spent time in the UK and really admired that stiff upper lip British mentality, and she really inspired us all to just come together, eat dinner, have candles, have flowers, set the table, make an effort, feel like you're really living life, because in the midst of all that it was so easy to forget that you were."

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveAlthough the kidnappers slightly lowered the ransom, they were still demanding millions from the family, who could not pay this kind of sum - and then came a painful silence.

The kidnappers stopped all contact for a month.

In that time, Miles started to long to hear the "nightmarish" voice of the kidnapper again.

When negotiations resumed, Farc expected the family to raise their offer, but they didn't, and this incensed them even more. They cut off contact again, this time for two months.

Susan Hargrove busied herself trying to break this silence - she sent letters into the mountains, spoke to former kidnap victims who had been held by Farc and to priests who worked in the area where Tom was rumoured to be held.

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveThe family had decided to increase their offer to $201,000 (£153,000) and they put this to the kidnappers when negotiations finally resumed.

"There was this huge pause," says Miles.

"I remember that pause," says Robert, "Like 'Come on! Say something - tell us, yes or no!'"

The kidnappers agreed.

Nine months after Tom had been taken he would finally be able to return home to his loved ones.

To this day, Miles can't disclose how the family obtained the money, but they did, and concealed it in crates.

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveThen it had to be delivered.

"Everybody had told us that you don't want to go up as a family member [and] physically carry the money. Because they'll just take you as well," says Miles.

"We had an FBI agent who'd grown close to our family and he knew a professional drop man who we could hire to actually take the money up to the mountains on our behalf. Our neighbours found a driver who was willing to drive an old beat-up truck.

"The two gentlemen that we chose did not know each other, and that was all part of the plan in a sense, because if they had no prior relationship it wouldn't give them much of a chance to make any plans to run off with the money."

The money was safely delivered and they waited for Tom's release.

"It's not like in the movies - you hand over the money and your dad's standing over there on the other side," says Miles. "It doesn't work that way. They took the money and really didn't explain anything else in terms of when he would come home, but through everybody's experience that we had talked to, we were under the impression that he would be back within three days to a week."

Three days went by - no sign of Tom.

A week went by - still no sign of Tom.

The weeks progressed and everyone was overwhelmed by a sinking feeling that maybe Tom wasn't going to be coming home after all.

Then they received a phone call from the kidnappers, instructing them to switch on the television immediately.

A news report showed the bodies of two American missionaries who had been held by Farc for a year and a half. The military had attempted a rescue, but their captors had executed them and fled the camp.

"I'll never forget that news story," says Miles.

"It was one of the most horrifying things I've ever seen - because the footage was so graphic, but mostly because we knew the family, we were well aware of their kidnapping. That could have been us and we knew it. That could have been our dad, and it was now a month after we'd paid this ransom."

The footage made the Hargrove family desperate and his mother Susan, against all advice, decided on a dangerous strategy - to make their story public.

"It was a very risky thing to do," says Miles. "I mean almost rule number one at the time was to not talk about these kidnappings, because this just drives up the price of the victim. But she felt if she put some sort of public pressure on the guerrillas, basically saying, 'We've lived up to our end of the bargain, what about you?' that would create some kind of pressure on them to do something."

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveTwo days later, the kidnappers got in touch. They demanded a further $130,000 (£99,000) to release Tom from captivity. It's possible they thought Team Tom would now be so afraid that they would be prepared to pay more.

Miles says they asked for confirmation that Tom was still alive, but the proof of life they received was not convincing.

"There was nothing there that proved that he was actually alive on the date that he said he was alive. He could have written any date with a gun pointed at his head and we were advised not to accept it," says Miles.

But the situation in Colombia forced them to make a decision very quickly.

A member of the Cali drugs cartel named Gilberto Rodríguez had been captured by the army, creating a menacing atmosphere in the city.

"We lived in one of the nicer neighbourhoods in Cali and that's where the drug lords happened to live," says Miles, "so we were seeing helicopters landing in yards nearby, roadblocks were being set up everywhere."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the same time, rumours began to fly around that the army was planning to move on the Farc - and the family did not want Tom to get caught in the crossfire. So they took a risk and paid the kidnappers $110,000 (£84,000) on 13 August 1995.

The ransom money was dropped off by a Catholic priest and the same driver they had hired for the first payment. When the money was handed over, Farc was supposed to tell the drop team where Tom could be retrieved, and they would use radios to relay the instructions to an International Red Cross ambulance standing by. Instead, Farc stole the radios.

"That was where things got really bad, because the guerrillas had agreed to release my dad simultaneously with the ransom payment and they didn't," says Miles.

"The only information they offered up was that he would be in a town close by a few days later, so that was our only hope."

The Red Cross team went to the town and waited all day, but there was no sign of Tom.

The situation seemed hopeless.

"That's when we were at our absolute rock bottom, because there was no road map for us any more," says Miles. "We were having a hard time sort of looking each other in the eye and accepting what was going to come next."

Robert, the young negotiator, says he felt very frustrated. "I failed, I didn't like that," he says.

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveBut nine days later, on 22 August 1995, Miles, Geddie and Robert were in the kitchen about to start making dinner when they heard a noise outside.

"We stepped right outside of the kitchen and I just could not believe what I was seeing," says Miles. "There was my dad standing there with long, orange hair, this long crazy beard and this poncho. It was one of the most shocking things that I've ever experienced in my life and oh my God, I ran to him and grabbed him."

Miles's mother Susan was in her bedroom. She was on the phone to Tom's brother Raford, discussing what they could possibly do next, when Tom burst in.

"She screams and drops the phone, so my uncle, who was on the other line, he's hearing the screaming and his assumption is that the guerrillas had come in to take another family member or that maybe my dad's body had been dropped in front of the house or something," says Miles.

"My mum was sitting there in shock, just screaming, looking at my dad and my dad had to go over and embrace her. She was bawling at that point, it was one of the most explosive, emotional moments you could ever envision."

Miles had assumed his father's hair, which was usually silvery white, had been dyed, but he found out later that it had turned orange because of a vitamin deficiency. Tom had been starved as well as chained in captivity - he hadn't been fed any vegetables for over four months.

Miles Hargrove

Miles Hargrove"They were mostly teenage soldiers, a lot of them were 14 and 15 years old and had had no education whatsoever. My dad had a PhD, and at one point realised that he had more years of education than all of his 10 guards combined," Miles says.

On the day of the release, Tom woke up and was told: "It's your time to leave."

He was dropped by the side of a road and after getting a lift to the nearest town, travelled from place to place, with the help of others, until he finally made it home.

It was a good outcome, but the family were traumatised, and the different ways they dealt with it created a rift in the family. Miles, his brother and mother wanted to put it behind them.

"We had formed a team with one goal in mind, and that was to get my dad out. We accomplished it, and so we were done and at that point we really wanted to shut down," says Miles.

Tom, on the other hand, was desperate to talk about what he had been through.

"He had this incredible need to share his story and to talk about it and talk about it and talk about it," says Miles.

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveWhen the family was meeting friends, this would suddenly change the atmosphere.

"The family just wanted to be normal and talk about normal things. Inevitably, the subject of the kidnapping would be brought up and my dad would hold court," Miles says. "They were always long, intense, moving discussions. It could wear you down sometimes, particularly when the mood before had been jovial and light-hearted."

Reliving the worst year of the family's life over and over again put a particular strain on his mother, Miles says.

When the family moved back to Texas, Tom went on to lecture about his experiences to various organisations, including anti-terrorism agencies and security firms, but Susan had changed.

"My mum had been raised overseas. She loved her adventures, she loved travelling the world and now for the first time in her life she had no interest in it whatsoever. She didn't really want to leave the house very much. I don't mean to say that she was a complete hermit, but her spirit for adventure, that was gone forever."

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveMiles says he will always be grateful to his friend Robert for his part in saving his father.

"We all felt so mature at the time," says Miles. "But as I've gotten older I realised we were just kids, and it's unbelievable to me that we could have ever justified putting this kind of pressure on Robert. I'm shocked that the adults in the room thought that that was a reasonable thing for us to do, but we had no other choice."

Robert says the experience did leave a mark on his student days; he was never quite as carefree again. While other students divided their lives between studying and partying, a part of Robert always remembered there were "bigger things in life than that".

He still lives in Cali with his wife and son, and works at the school that he and Miles both graduated from.

Miles, who is now 47 and lives in Texas, works as a filmmaker. During the darkest days of the kidnapping, he was constantly filming the family's experiences and has now turned that footage into a film.

Miles Hargrove

Miles HargroveThe documentary, Miracle Fishing, came too late for Susan and Tom, who died in 2009 and 2011 respectively. It was due to premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival in April this year, but the festival had to be cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

While Tom was driven to talk about his experiences immediately after his release, in Miles's case the urge grew as time went on.

"I have often thought that I came out of it fairly intact. But when I sit back and analyse, I've had this 25-year need to tell this story," he says.

"As much as I tried, I could never truly move on from the kidnapping - not with the footage I had. I knew it was special. I couldn't rest until I finally put it together."

Miracle Fishing has just won Best Film at Internationales Filmfest Oldenburg in Germany.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLi Jingzhi spent more than three decades searching for her son, Mao Yin, who was kidnapped in 1988 and sold. She had almost given up hope of ever seeing him again, but in May she finally got the call she had been waiting for.