'My brothers on Europe's last death row'

Belsat

BelsatAny day now, it's possible that two men will be executed in the only European country where the death penalty still exists - but their family will never find out when they were shot, or where they were buried.

Five months ago, Hanna Kostseva was in court when her two brothers, Stanislaw and Ilya, aged 19 and 21, were sentenced to death for murder.

"When the judge read out the verdict to 'apply an exceptional measure of punishment in the form of execution', people in the courtroom began to clap," she says.

"Initially, just one started, then another followed, then a third, and in the whole hall only applause was heard. For me, at that moment, it was like my own life was cut short."

Hanna says she then approached the cage in which her brothers had pleaded guilty to the murder of one of her neighbours. She managed to squeeze close to them and hug them through the bars, and promised she would do everything possible to save their lives.

In reality their fate was already sealed.

A month earlier, the president of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, had told a Russian radio station the case was under his personal control.

"They're scum, there's no other word for them. They have been in trouble before and have been punished. They killed a teacher - only because she wanted to save two of their sister's children. Their sister is a nothing - an asocial element. The teacher only tried to protect the kids and take them out of the family. These two were knifing her all night."

The brothers' appeal against their sentence was dismissed on 22 May. After that, the only option remaining was to ask the president for clemency.

Hanna Kostseva

Hanna KostsevaHis decision was probably made by Tuesday 2 June, and if he had decided to spare them it would most likely have been in the news, so the silence is ominous.

In his quarter of a century as Belarus's first and only president, Lukashenko has granted clemency on only one occasion.

Natalya Kostseva, the brothers' mother, was unable to attend the sentencing herself for a reason that may be hard for someone from another country to understand.

The story goes back 19 years, to the day when her husband died. Stanislaw, the youngest of her four children, was then five months old. Ilya was already two.

To feed her family, Natalya worked as a milkmaid on a collective farm. Subsequently she got a job in a transport company, where her shifts sometimes ran late into the night. Stanislaw, Ilya and their older brother were often left in the care of Hanna, the oldest child.

Natalya admits she wasn't a perfect mother. Visiting social workers would enjoy her home-made pies but would also note in their reports that she'd been drinking.

Nevertheless, family photos show a younger woman hugging well-dressed children and grandchildren protectively.

Natalya Kostseva

Natalya KostsevaNatalya held out for 13 years. It was when Stanislaw and Ilya were 14 and 16 that they were finally taken away for fighting and skipping school, and placed in a state-run children's home.

In Belarus, when children are taken into care, their parents - in this case, Natalya - have to foot the bill. She still owes 10,000 Belarusian roubles, or about $4,000, so each month a third of her meagre salary is taken by the state, and this will continue for the next eight years, long after her sons' execution.

This is the reason Natalya was unable to travel to visit them in prison in the eastern city of Mogilev, and was unable to attend the hearing when they were sentenced: after she'd missed some payments, a court had ruled that she could not leave the capital, Minsk, until the debt was paid in full.

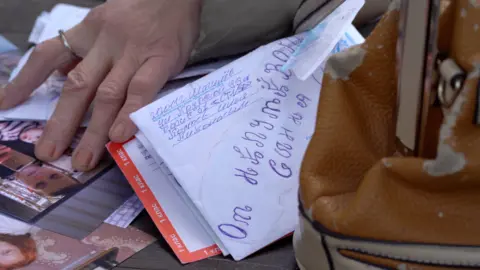

Since her sons were arrested in April 2019, her only contact with them has been by letter.

The family doesn't dispute that the two young men are murderers and deserve to be punished.

"I'm not justifying them in any way - they are guilty, you shouldn't take a person's life. In one moment, they crossed out someone's life as well as their own and ours," says their sister, Hanna.

It happened soon after Stanislaw's 18th birthday, when - finally released from the children's home - he had gone to stay with Hanna in the house they lived in as children, in the town of Cherykaw, close to the Russian border.

Ilya had already left care on his 18th birthday, two years earlier.

But any joy at being reunited didn't last long. Just a few days later the two brothers went to take revenge on a neighbour - a teacher, who had complained to social services about Hanna's children and suggested that they too be taken into care. Stanislaw and Ilya stabbed her to death then set the house on fire, and were quickly arrested.

After the applause in the courtroom, Hanna says she was hounded out of town.

On one occasion, while her partner and her oldest brother were away working in Russia, someone even tried to break down her door, she says. She then moved into a tiny flat in a former military barracks 140km (90 miles) away, occasionally making a six or seven-hour trip on trains and buses to Mogilev, carrying heavy bags of food for her brothers.

She met each of them separately, because they are forbidden to meet or even write to each other.

It was only after the verdict that Hanna learned that other countries in Europe, including neighbouring Russia and Ukraine, no longer have the death penalty. It was a bitter discovery.

Killers should be sentenced to life in prison, she says.

"Not everyone leaves prison alive, but you have to live through it, to bear it and then be released with a sense of repentance. The death penalty is denying the right to repent."

Death in Minsk

- It's thought that more than 400 people have been executed since Belarus became independent in 1991, though numbers have dwindled to a handful per year

- The death penalty has not been carried out in any other European country since 1996

- President Lukashenko rejects calls for a moratorium citing the "will of the people" - a 1996 referendum in which 80% voted in favour of capital punishment

- Women cannot be sentenced to death in Belarus, only men

In court, the brothers begged the victim's family to forgive them, and both have since asked to see a priest, Hanna says.

They have now been moved to a detention centre in the centre of Minsk, close to the Gorky Drama Theatre, a museum of the history of Belarusian cinema, McDonalds and TGI Friday's.

It's an open secret that this is where executions have been carried out for decades.

"Everything is exactly how it was in the Soviet days," says human rights activist Andrey Poluda. "Not a thing has changed. The relatives are not given the bodies of the executed prisoners, they are not told the time of death, the place of the burial is unknown."

A single executioner uses a pistol, according to a former director of the facility, Oleg Alkayev, who now lives in the West.

"During the execution a doctor is present who later confirms the death. A prosecutor is present, too. Sometimes, when I'm on the metro in Minsk, I look around and I wonder if a person who is a part of that system is travelling now, too," Poluda says.

Natalya cannot come to terms with what is about to happen. "If, God forbid, I lose them, I won't go on living - I don't want to," she says.

At some point after the execution has taken place, she will receive a package containing her sons' belongings and an official letter. In it, she will be told that the death sentence has been carried out, and nothing more.

Read Tatsiana Melnichuk and Tatsiana Yanutsevich's report for BBC News Russian

You may also be interested in:

Earlier this year, two guards who worked at a prison in Yaroslavl, north-east of Moscow, were jailed for abusing an inmate. Despite official claims that Russian penitentiaries are cleaning up their act, prisoners, their relatives and human rights activists tell a very different story. The BBC's Oleg Boldyrev investigated one recent case.