In mid-Pacific with nowhere to land

BBC

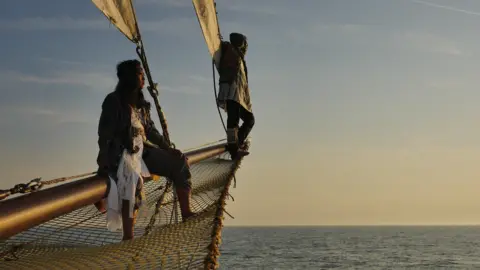

BBCA group of performers were halfway across the Pacific Ocean in a 75ft sailing boat when the coronavirus pandemic erupted. Suddenly countries began closing their sea borders - leaving the vessel with no guarantee of a safe haven before the start of the typhoon season.

When the crew of the Arka Kinari left Mexico on 21 February they, like everyone else, were aware of the coronavirus. They had no idea, though, how soon it would affect them and how seriously. They say they joked about it being just a Mexican beer. But approaching Hawaii six weeks later, they picked up a radio signal.

As their boat sliced through the waves, they clustered on the foredeck around the tiny radio, intently listening to a crackled voice announcing that Pacific islands, such as the Cook, Christmas and Marshall Islands, were all closing their borders.

"This really brought it home to us that the whole world was really shutting down," says British crew member Sarah Louise Payne.

They had set out from the Netherlands in August - two musicians with a multinational seven-person crew, including lighting and sound engineers, heading for Indonesia, the country they planned to make their base.

Grey Filastine and his Indonesian partner Nova Ruth had spent years flying around the world performing at music festivals, playing their unique mix of traditional Javanese melodies and contemporary electronic music.

Their lyrics focused on environmental and social justice, and Grey says he and Nova were "frustrated about our complicity with the very same fossil capitalism that we're denouncing in our performances".

So they had an idea - to create a multimedia performance on board their boat with a message about the climate crisis and the health of the oceans. Finally, they would have "a method that matches the message", Grey says.

The ship would have an engine for emergencies, but they would use it very sparingly. Essentially, it would be carbon-neutral travel. Grey believed it was important for musicians to demonstrate that this was viable: "We can imagine life after the carbon economy and re-engage with the last great commons, the sea."

They sold a share in a house in Seattle, and bought the boat. Nova originally wanted to build an Indonesian Pinisi sailing boat, but that would have required large amounts of tropical hardwood so they ended up recycling an old two-masted steel-hulled schooner. The sails double as screens during their performances.

Nik Gaffney

Nik Gaffney"When we saw it, the two sails were similar to the Pinisi, so it was close to our dream," says Nova, whose mother's family are from the Bugis, a seafaring tribe.

"As a descendant of the Bugis I feel sad that I haven't learnt to sail, and very few of my generation do," she says. She was also motivated by the fact she has been told that women from the Bugis tribe shouldn't sail, "so it's become my personal mission to do so".

Bugis

- From the Indonesian island of Sulawesi

- Well before the European colonisation of South East Asia and Australia, Bugis sailors are believed to have traded across the region including Australia - their boats are found in ancient Aboriginal rock and bark paintings

- Some say that the word "bogeyman" refers to the Bugis or Buganese pirates - ruthless seafarers that you wouldn't want to cross

For Sarah it was a perfect gig as she is a sailor and a lighting technician - alongside having "a great love for this Earth of ours and the need to help protect it".

Fellow British crew member Claire Fauset joined the expedition after falling in love with "the crazy plan and the beautiful boat and of course, the zombie apocalypse survival team that is this crew".

Grey and Nova borrowed money, around £250,000 (€300,000), so at some point the project needs to generate money, either through performances or taking on paying passengers. This has also been put in jeopardy by the coronavirus pandemic.

"Arka Kinari is a massive undertaking, it had already stretched us to the limits, physically, financially, emotionally, and then this happens," says Grey.

After rebuilding the 1947 schooner in Rotterdam, crafting and rehearsing the on-board performances in Europe, the Canary Islands, Panama, and Mexico, they were mid-Pacific when the coronavirus outbreak became a pandemic affecting every country in the world.

Grey and one other crew member, both US citizens, could have stayed indefinitely in Hawaii. The others - the Brits, a Spaniard and a Portuguese - got visas for a month, allowing them to restock with fresh food and regain their land legs. Nova had flown home from Mexico to prepare for the ship's arrival.

During their time in Hawaii the rest of the crew monitored the spread of lockdown measures from one country to another. Soon enough, Indonesia announced a ban on all foreign arrivals by sea or air until further notice.

"I got the taste of ashes in my mouth. You could describe that as a personal meltdown," says Grey.

Before setting off, they had made a Plan B for just about any eventuality - or so they thought. Their route had doubled in length to avoid piracy off Somalia and the war in Yemen, but the coronavirus was a complete broadside.

"In practical terms our plans would have been less disrupted by World War Three, because at least warring states don't close their borders to the ships of allies," says Grey.

On 6 May, with the US visas about to expire, they decided to head for Indonesia anyway hoping that it might open its borders before the start of the typhoon season in June - but with no clear idea where they would go if it didn't.

Before departure they were plagued with doubts and indecision. One crew member decided to bail out at the last minute. For the rest of the crew, with typhoon season bearing down on them, "we had to put such apprehensive thoughts about borders closing aside," says Sarah.

Now, three weeks later, fresh food is running low, but there is enough dry food to last a couple of months. Fresh water is not a problem thanks to solar-powered desalination equipment on the vessel.

They are growing a few spindly lettuces on board as an experiment and catching fish with home-made lines and lures.

This involved a change in diet for some of the crew. "Veganism is a great choice on land, where plants grow - but we're on the sea, where the fish live," says Grey.

They are now sailing at around 13 degrees latitude, and if they see any circular storm developing they will route south. Worryingly, the navigation system has broken so they are navigating by iPhone.

"While we do have some paper charts, an iPhone is now our most full-featured navigation tool. That might sound pathetic but it's far more information than the Polynesians or Captain Cook had to cross the Pacific," says Grey.

If they could stop somewhere with internet, the problem with the main navigation chart plotter might be resolved, Grey says. They also need to anchor somewhere, even an uninhabited atoll, to fix some problems that developed in the rigging.

But they don't know when or where they will next be able to land.

"And as we slowly sail towards Indonesia the worries about landing are eclipsing the worries of the sea," says Grey.

At sea, everyone takes turns doing the necessary chores. During the dayshifts they steer the ship and carry out any sailing manoeuvres, enter data into the logbook, monitor the engine and grease the propeller shaft.

The morning shift involves cleaning the solar panels, washing the dishes, swabbing the deck and inspecting the fresh food, while the afternoon is for big infrastructure projects, repairs, wood maintenance and carpentry, de-rusting and painting the steel hull.

And then at night the only responsibility is to keep to the course and look out for hazards. The Arka Kinari doesn't stop.

"It's just you, the heavens above and infinite sea around," says Grey.

"On moonless nights your eyes become so light-sensitive that the rise of Venus and other planets casts a reflective path on the sea that we normally only experience from the Sun or Moon."

Not only can you see the bow wave perfectly illuminated by starlight, he says, but the agitation of the water causes "trails of bioluminescence, like underwater fireflies or grinder sparks".

"If I bring the right music along, I can pass the whole two hours of my night watch breathless, in goosebumps."

Back in Indonesia, Nova has been trying all her contacts to get permission for the Arka Kinari to land, but without success. Grey, as her spouse, might be allowed in, she gets told, but not the rest of the crew.

Recently they passed Johnston Atoll, a US-administered territory once used for testing and storing chemical and biological weapons. They asked for permission to land, but there was no reply.

"Never thought I'd be asking a nuclear waste dump for refuge," says Grey. "Given it has a three-mile security perimeter, we didn't dare get any closer."

Next try was the Marshall Islands - completely closed.

Along the route ahead are some islands evacuated after contamination by US nuclear tests in the 1950s, which would not be safe to live in permanently, but perhaps safe enough for a short visit.

This could be the only place, Grey thinks, where they might be unnoticed or tolerated, and somewhere they could try waiting for a while.

He points out that barring the boat is irrational, because they have been effectively quarantined at sea.

"Lawmakers didn't consider the fact that we spend weeks at sea in the strictest of quarantine. It's us that are at risk from land-dwellers, not the reverse."

They are going slowly, intentionally, aiming to reach Indonesian waters in early July, hoping that by then they will be allowed to enter.

If they can't, the Arka Kinari will need to seek refuge from the typhoons elsewhere, preferably a country not far away - if there is one that will have them - from which they can make a dash for Indonesia between typhoons, when borders open.

On the project website they have announced all scheduled performances are suspended. When this crisis finally does come to an end, it states, the Arka Kinari will be ready to begin its role inspiring people through music to build a better future.

You may also be interested in...

Alamy

AlamyFew Australians are aware that the country's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had regular contact with foreign Muslims long before the arrival of Christian colonisers. And Islam continues to exercise an appeal for some Aboriginal peoples today.