'I left her as a baby - 16 years later she saved my life'

Getty Images

Getty Images

After losing everything in the horror of Hurricane Katrina, artist Matjames Metson was broke, traumatised and "braced for the end" when he received an unexpected phone call. It was from the daughter he hadn't seen since she was a baby, and it gave him a reason to live.

Matjames Metson was 16 when he met the future mother of his child.

"Selanie walked into my American history class and I was just blown away. I was like, 'Oh my God, who is that?' It was an instant: 'I need to know who that person is.'"

Matjames's parents were artists, and his stepfather worked as an art professor at a succession of different art schools.

"We moved endlessly, it seemed like," Matjames says, "and I'd never really had an opportunity to make actual friends. I'd meet people and then we would leave and so it always gave me this distance that I still hold on to today, I think."

After a stay in the south of France, the family moved to the small town of Yellow Springs in Ohio, where he met his first girlfriend, Selanie.

"We got together and we had a relationship for several years and then it had actually ended, but we had what they call now 'a hook-up' and Selanie became pregnant," says Matjames, "but we were still not a couple."

Matjames was 18 years old and didn't feel ready to become a father.

"I was utterly terrified. It threw my world upside down," he says.

"I didn't have the faculties to deal with it in any sense. I was too young, too naïve and I didn't know what to do."

Selanie gave birth to a little girl called Tyler.

Tyler Hurwitz

Tyler HurwitzAfter she was born, Matjames met Selanie at the entrance to the Glen Helen Nature Preserve, and he cuddled the baby for the first time.

"I held Tyler in my arms for about 30 seconds I'd say, and that was it.

"I didn't understand that it was my child on an emotional level. I knew biologically I was involved and I was just like, 'Oh my God this is just really heavy. I don't know how to react to this, I don't know what to do.'"

Matjames says it started a lifetime of running away - from everything.

"It's classic fight or flight. Having zero self-esteem at the time, I chose to run and continued to do so."

After stays in Montreal and Boston, Matjames eventually arrived in a bustling and vibrant New Orleans around the age of 19 or 20.

"I was a kid, I was young for my age, emotionally, and all of a sudden here I am in a very exotic, very different place. It was a good place to hide, I suppose."

But if he was hiding from his past, he couldn't completely escape from it.

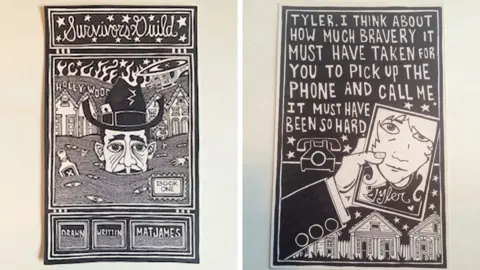

In a graphic novel Matjames produced later about his life, a sketched image shows him hunched over, carrying the heavy weight of guilt on his shoulders. It felt like carrying a "16-tonne block of burden" around, he says.

This contributed to a mental breakdown that left him in an institution "for quite some time" he says.

When he was discharged he gradually became a well-known face in the city's French quarter, famous for its nightlife, its music and free-flowing bourbon.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I went in as a fairly anonymous resident of New Orleans, but I came out and it gave me some sort of mystique, and suddenly I knew everybody. I was living in someone's closet and I didn't have anything except for my pens, so I'd go to the coffee house, the bar or wherever people were and I was embraced as a character and a spectacle," he says.

He'd always been an artist, but now began getting more attention. As he didn't have a permanent home, all his work had to be on paper.

Later, as he became more of a "domesticated creature", he started making assemblage art - finding objects and gluing them together into sculptures.

New Orleans was a treasure trove for this he remembers. Wherever you looked - even on the ground - you could find the artistic equivalent of gold dust- such as early American photographs that were 100 years old. He would find beauty in repurposing materials such as wooden matches and lolly sticks.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd he was successful, making art "like a fiend" and exhibiting at shows in the city, while supporting himself by working in bars, and riding around the city on his bicycle, delivering pizza.

Meanwhile his daughter, Tyler Hurwitz, was growing up in Yellow Springs with her mum, Selanie, another talented artist. She remembers accompanying her mother on an upholstery apprenticeship at the age of four.

"I was submerged in a creative environment from the time I was born basically, and that has never ended," she says.

Her home was a happy one. Selanie had got married and had another daughter, and growing up in this tight family unit, Tyler says she didn't take a great interest in her biological father.

Tyler Hurwitz

Tyler Hurwitz"I had so many people and family and friends surrounding me all the time, I guess I just didn't really think about it," she says. "It wasn't something that had ever existed in my mind, so it wasn't ever a huge question as to who my father was, or where he was, or why he wasn't there.

"I never asked, therefore I didn't really know."

Like her mother, she became an expert at upholstering furniture and a skilled artist.

By the age of 30, Matjames was considered one of the city's "home-grown" artists, despite the fact he'd lived the first two decades of his life elsewhere. He also had a permanent job restoring antique builders' tools. His two dogs, Pikachu and Pearl, were everything to him.

"Suddenly I was like… 'I can't believe I've survived to 30,'" he says. He'd had a "live fast, die young" mentality, and decided it was now time to slow down. First he moved out of the French Quarter, then he left New Orleans altogether for a few years, returning in the spring of 2005.

"I get an apartment, I unpack my stuff and that's when Katrina hit," he says.

Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in August 2005, flooding large areas of the city. Nearly 2,000 people were killed and one million displaced, and there was a terrifying breakdown of law and order.

"It was utter destruction," says Matjames, who is still distressed by what he witnessed. "If I close my eyes I can still see it.

Getty Images

Getty Images"There was a lot of loss of life, everything was completely broken. The stores weren't open, the groceries weren't open, the crime was insane. There's so many people just losing their houses and possessions, it was nothing more than just utter desperation on everybody's part."

Matjames's apartment was waterlogged and he lost most of his belongings, including almost all of his artwork.

Fearing that he might not be able to take his beloved dogs with him, Matjames remained in the wreckage of the city for eight days, until one day he found a working payphone, called his mother to let her know he was safe, and then called a friend, who helped get him, Pikachu and Pearl to Los Angeles.

He moved into a very small apartment on a busy intersection in the LA district of Koreatown, with demolition crews busy all around.

"Once I'd moved into this flat they literally tore down every building surrounding me. So the little four-storey building I was in suddenly was infested with mice and cockroaches and meth heads," he says.

"Someone gave me a futon, I had a little black and white TV and maybe a couple of T-shirts and that was it."

Henry Cherry

Henry CherryMatjames says his dogs were not only his best friends, but also his children, his confidants and even his eating partners.

"When I got regular food they'd get some," he says. "And when I didn't have regular food I'd eat some of theirs. I'd reach in the dog food bag and eat handfuls of dried kibble."

He found a job in another part of the city, working as a "stock boy" in an art supply store for $7 (£6) an hour, but would have to beg for change for the fare to travel there.

Whenever the phone rang, it would be bad news about a friend from New Orleans suffering from the after-effects of the storm.

He thinks many of them had post-traumatic stress disorder, the consequences of which could be devastating. "Some people drank, some people took narcotics, some people committed suicide."

Matjames says he shut down emotionally, and would sit in his apartment just staring at the television set, not even changing the channel. He couldn't make art and says he was "braced for the end".

"My capacity for self-preservation was slipping and slipping and slipping and I had nowhere to really turn," he says, "until the phone call which not only saved my life, but it changed my life."

Tyler, who was then 16, was cleaning her bedroom when her mum came in and handed her a piece of paper. On one side was a PO Box number, and the other a mobile phone number. Her mum told her this was how she could contact her biological father.

"I think that she just kind of stumbled upon it in a stack of papers and was just like, 'Oh, better give this to Tyler in case she wants to call,'" Tyler says.

"It was just like a very nonchalant thing that she'd just done, and she specifically asked me to write instead of call, but minutes after she gave me the paper I called the number. I think half of me really was not expecting anybody to answer, so I didn't put much thought into it.

"I kind of had this mentality of, 'I've got nothing to lose.' So when he answered, I wasn't emotional, and I wasn't nervous."

- Matjames Metson and Tyler Hurwitz spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service (producer, Mariana Des Forges)

- Download the podcast for more extraordinary stories

She says she hadn't even made a conscious decision to call, she was simply acting spontaneously.

Matjames feared it would be more bad news about one of his friends - and then he heard Tyler's voice.

"Have you ever heard the name Tyler before?" she said.

Matjames replied: "Tyler, I've been waiting for this call for 16 years."

"Then I said, 'Do you hate me?'" says Tyler.

"I said, 'I really don't hate you. Do you hate me?'" says Matjames. "And she said 'No.' Like here I am, a total messed up, traumatised artist guy who had zero to offer her, but we talked about music and we talked about this and that."

Tyler says that as they finished the call they didn't plan how to stay in touch, but just knew that they could call each other if they wanted to.

For Matjames, the call was life-transforming.

"I really feel as though my spine straightened and my eyes opened and I stopped looking on the ground and started to say, 'Well OK, here I am in Los Angeles, my daughter thinks that's amazing, maybe I should think that's amazing?'"

He says he wanted to impress Tyler and the only way he felt he could do this was through his creativity.

"I'm not going to be able to do it with my home or my bank account or my clothes. I'm going to be the best artist I can possibly be, and that is something I have picked up and have not put down, and I owe that all to Tyler."

Tyler Hurwitz

Tyler HurwitzAs he slowly got himself back on his feet, he began to produce and exhibit his work again. He was able to move to a better apartment and a few years later, as a new exhibition of his work opened, Tyler flew to LA to meet him for the first time.

"I was nervous, which I feel is understandable," says Tyler, "but then the second that we were acquainted it just felt OK, it felt natural and normal and I was perfectly content with being myself."

She instantly noticed the physical resemblances too.

"I have curly hair and my mum has pin-straight hair and it's always been a situation trying to figure out how to deal with my hair," she says. "So when I met Matjames I was like, 'Well, we both have curly hair, that explains it.' And we have similar hands and we both have green eyes."

One of the first pieces of art that Tyler says Matjames showed her was an intricate sculptural assemblage tower.

"If you open this door and unlatch this thing and you slide this over, you'd look down in there and in between a bunch of nails you'd find my name," she says. "So my name is hidden in a lot of his work, you have to search for it, but it's definitely there and it's just kind of cool knowing where to look."

She believes this symbolises the motivation that she provided for Matjames to resume his work as an artist.

Cartwheel Art

Cartwheel ArtHaving visited Matjames in his artistic habitat, Tyler later challenged Matjames to visit hers in Ohio.

"I knew she was right and I had to do it. It was like resetting some sort of machine," he says.

"It was a way for me to suddenly become my age and grow up and stop being the teenager who ran."

While he was there, Tyler was re-upholstering a sofa and Matjames got to help with the project and witness his daughter's artistry at work.

"My whole inspiration behind upholstery and my love for furniture and fabrics was initially inspired by my mother," says Tyler, now 29. "So the sofa was really a project where the brains of all three of us came together."

Tyler Hurwitz

Tyler HurwitzMeeting Matjames has also meant that she has connected with his parents - his mother, stepfather and father - all of them artists.

"To be a creative person and then suddenly find your long-lost family, only to find out that literally every single one of them are artists - it's wild," says Tyler, who, inspired by her grandparents, is now studying again in the craft and material studies department of a university in Virginia.

Over the years, Matjames and Tyler have talked a lot about why he left her.

"She understands why I had to go," says Matjames.

"We talked a couple of weeks ago. She was like, 'You couldn't have lived here, it wouldn't have been the right thing for you, no matter what.' So it's nice to have the person that I left clearly understanding why I had to do it and not resenting me for it, which is huge and brave and really remarkable."

Tyler acknowledges that there is a social stigma associated with fathers who leave a family, but says what Matjames did was right for him, and ultimately for her too.

Had she adhered to "societal standards" and judged him negatively it would have achieved nothing, she says. Instead she has gained a new family, a new source of inspiration, and is "living a great life".

Listen to Matjames Metson and Tyler Hurwitz speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

You may also be interested in:

Rachel Mason

Rachel MasonIt wasn't the most obvious career choice for Karen and Barry Mason, and not one they could talk about openly. But for years the couple ran LA's best-known gay porn shop, and distributed adult material across the US.