The 'womanspreading' placard that caused fury in Pakistan

Facebook

Facebook

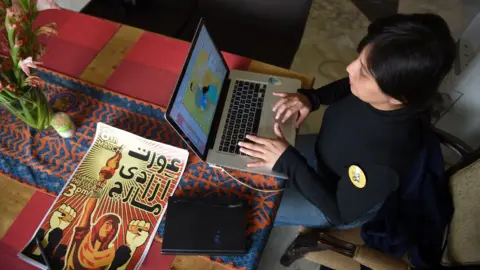

When Rumisa Lakhani and Rashida Shabbir Hussain created a placard for an International Women's Day march in Pakistan, they had no idea just how much it would place them at the centre of a fierce national debate.

The day before the event the two 22-year-old students attended a poster-making session at their university in Karachi.

They wanted to come up with something that would attract attention and started brainstorming ideas.

A friend happened to be sitting with her legs spread wide, and this inspired the poster that Rumisa and Rashida made.

For Rumisa the way women should sit is a constant issue. "We have to be elegant; we have to worry about not showing the shape of our bodies. The men, they manspread and no-one bats an eye," she says.

Rumisa's design depicted an unashamed womanspreader nonchalantly lounging in sunglasses.

Her best friend Rashida then provided the slogan. Rashida wanted to draw attention to the fact that women "are told how to sit, how to walk, how to talk".

Rashida Lakhani

Rashida Lakhani

So they decided on the caption: "Here, I'm sitting correctly."

Rumisa and Rashida met in their first year at Habib University. Rumisa studies communication design, while Rashida is a social development and policy student.

"We are best friends, we laugh together, tell each other everything," Rashida says.

They share a passion for women's rights, based on their personal experiences of sexism.

For Rumisa, dealing with the family pressure to get married has been a "daily struggle". She sees the fact that she isn't married today as "a personal victory".

Rashida says she faces constant harassment on the streets. She also finds the expectation that she should marry and become a housewife uncomfortable.

So the two friends were keen to participate in one of several "Aurat" marches - named after the Urdu word for women - staged in cities across Pakistan last month.

"It was an amazing feeling, having so many women screaming for their rights," Rumisa says. "It was our space at that moment and I think all who attended could feel that empowered vibe from it."

The Aurat marches were a big moment for the country's feminist movement. While women had marched in huge numbers in Pakistan before, these protests cut across class divisions and also included members of the LGBT community.

In 2018 the World Economic Forum ranked Pakistan as the second-worst country out of 149 in terms of gender equality - the only country with a worse ranking was Yemen. Women in Pakistan regularly face domestic violence, forced marriages, sexual harassment, and can be the victims of honour killings.

Some placards and posters on the Aurat marches were sexual in nature, and in this conservative country these triggered a backlash.

The march organisers attribute this response to the fact they were challenging the notion that men should make decisions about women's bodies.

"We were questioning body policing, the policing of women's sexuality," says Moneeza, one of the national organisers. "In the religious community there is the notion that a woman should cover herself and stay at home. We were challenging that."

Rumisa believes the sight of 7,500 women gathering on the street shocked conservatives. "Doing that on the road with such a loud voice made people uncomfortable," she says. "People feel it's threatening Islam, although I don't see that. I think Islam is a feminist religion."

Even before she had got home from the protest, Rumisa realised the picture of her with the placard had gone viral on social media.

One comment on a Facebook post said, "I don't need this kind of society for my daughter"; while another said, "I am a woman but I certainly don't feel good about this. Show that we belong to an Islamic society." Another read, "It was women's day. Not bitches' day."

However, others supported the placard's message.

One woman tweeted: "I genuinely don't understand why people are so horrified by words on a poster when they should be disgusted by the subjugation of women in Pakistan."

Rumisa received messages from people she knew saying, "We can't believe you did this. You're from such a modest family."

Rashida Lakhani

Rashida Lakhani

Members of Rumisa's extended family told her parents that they shouldn't let her go on any more marches.

Despite this pressure, Rumisa's parents supported their daughter's decision to protest.

Another placard at the march said "my body, my choice".

According to the Samaa TV channel, this led to one cleric in Karachi ridiculing the slogan in a sermon that was posted online.

"My body my choice… your body your choice… Then men's body men's choice… They can climb onto anyone they want," Dr Manzoor Ahmad Mengal is reported to have said in a video posted online.

He has been accused by critics of inciting rape, and march organiser Moneeza says that rape and death threats have been commonplace since the protest.

"There has been a backlash on social media with a lot of organisers getting rape threats," she says. "I think that is part of the wider misogyny amongst men that we are challenging."

The Aurat marches also caused divisions within Pakistan's feminist movement.

"A lot of feminists participated in the backlash, self-proclaimed feminists. They were like, ' these are not valid issues, this is not the way women should behave'," Rumisa says. "My own friends - who call themselves feminists - felt my poster was unnecessary."

One prominent feminist, Kishwar Naheed, said she believed that Rumisa and Rasheeda's placard, and others like it, were disrespectful to traditions and values.

She said that those who thought they could secure more rights using such placards were misguided like jihadis who think that by killing innocent people they will go to heaven.

However, an article by Sadia Khatri in the Dawn newspaper accused Kishwar of letting feminists down.

She called on those seeking change to embrace the "vulgar" nature of some of the posters.

FAROOQ NAEEM

FAROOQ NAEEM

"We need to claim these posters and make the connection between them and the 'larger' feminist struggles," she said.

"A girl's right to sit with her legs open is about her agency to do what she likes with her body without reprimand or harassment, it is about her right to move freely, it is about victim-blaming and whose fault it is when someone is assaulted — not the girl's, no matter how she was sitting."

Despite the controversy Rumisa doesn't regret making the poster. "I'm kind of happy that my poster got a lot of attention," she says.

"I'm not ashamed or afraid of that kind of attention, it's one of the reasons we use slogans like that because we wanted attention to be brought to the women's march and to all kinds of issues."