'The head injury that made me commit a crime'

BBC

BBCA head injury not only left Byron Schofield physically and mentally scarred for life - it also set him on the path towards prison.

The hammer blows landed, one after the other, on the side of Byron Schofield's head. It was an August evening in 2010, a month after his 19th birthday, and he was walking through his home town - Liversedge, West Yorkshire - with his younger brother, Reece.

As they turned down an alleyway, they were followed by a group of men and without warning, one of them began swinging the hammer at Schofield.

Although his memory of the incident is fuzzy, he's sure he had never met the attackers before, and they didn't rob him - so why they did it is a mystery. No-one has ever been prosecuted.

In hospital, Schofield was diagnosed with a brain haemorrhage and a skull fracture. Part of his skull was removed to relieve pressure on his brain, then he was placed in an induced coma for three days, under constant supervision. No-one knew whether he would survive, but he pulled through.

Six months later, when he was finally discharged from hospital, he had lost most of his strength on the left side of his body, his speech was slurred and his short-term memory was poor.

"A brain injury is nothing like a cut," Schofield says. "A cut takes a week or a couple of days to heal. But a brain injury takes years."

Once he was out of hospital, his mother became his full-time carer.

Doctors had recommended a specialist centre called Daniel Yorath House for further treatment, but the NHS said there was no room - the limited number of places were occupied by people in greater need.

For two years, Schofield's goal was to become well enough to live on his own.

But what he didn't realise was that the injury to his brain also had invisible effects that were lying in wait to wreck his new life.

Three months after moving into his own flat, Schofield went to a party a friend's house. There he saw a group of people who resembled the young men who had attacked him and before he could stop himself he had started a fight. The police were called, he was arrested, and sent to Leeds prison to await trial.

Experts say that any Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) can cause a person to experience problems dealing with their emotions, forming and keeping memories and - as in Schofield's case - controlling impulses. Often the individual also becomes more aggressive.

By some estimates a TBI will double your risk of ending up in prison, but one respected Swedish study, which collected and analysed data over a 35-year period, found that people with a TBI were four times more likely to be jailed than the rest of the population.

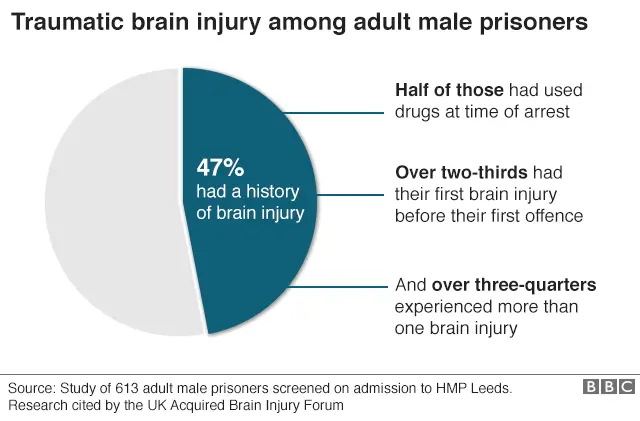

Research by neuropsychologist Dr Ivan Pitman for the Disabilities Trust suggests that about half of the UK's adult male prison population may have suffered a brain injury.

When Schofield arrived at HMP Leeds in March 2013, he was presented with a form to explain any health needs, in which he noted his head injury. But he had no meeting with a doctor.

Because of the weakness in the left side of his body he needed help washing and dressing, and couldn't carry a tray.

"I asked to be padded up with someone else," he says. "I had to get a cellmate to carry my food."

It was at this point that Schofield had a stroke of luck, and met James Liddement of the Disabilities Trust, who was embedded in the prison, screening new arrivals.

At Schofield's sentencing hearing, seven months after his arrest, Liddement told the court that he was too ill to serve a prison sentence and asked for him to be sent instead for treatment at Daniel Yorath House - the same place doctors had wanted him to be admitted two-and-a-half years earlier.

The court accepted the proposal and, to his great surprise, Schofield was able to leave prison that day.

He was given what was, in effect, an 18-month suspended sentence. At Daniel Yorath House he was would undergo daily neurorehabilitation exercises and physiotherapy, and if he tried to leave the centre without permission he would be sent straight back to prison.

When asked what difference it would have made if Schofield had been admitted to Daniel Yorath house in the first instance, Ivan Pitman replied: "Without a shadow of a doubt Byron would not have committed that crime."

The treatment involved training Schofield for everyday life, initially through role-play then by sending him out with tasks to fulfil in the real world. All these exercises were filmed and played back to Schofield for him to analyse. There would be a discussion about what he had handled well and what he had handled badly.

At first, if Schofield was asked to go to a shop and buy something, he would be accompanied. Staff would nudge him if he became too loud or aggressive and would monitor his interaction with members of the public. Later his minders would lag behind, providing no real-time support. And finally, they would let him go on his own.

During this process Schofield was not only being trained in how to behave appropriately towards other people, but also relearning how to control his own behaviour.

After several months at the rehab centre he was moved to a small flat in its grounds, as a trial run to see if he would be all right living on his own. He was.

While Schofield still has significant problems with speech and memory and the left side of his body remains weak his doctors are now confident that he can control his impulses.

A report published on Wednesday by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Brain Injury calls for a range of measures to improve services for the rehabilitation of patients who have suffered brain injuries. It argues that this would prevent crime, keep people like Schofield out of prison and save £5bn per year by speeding up patients' recovery and their return to work, and reducing the cost of community care.

Brain injury rehabilitation - APPG recommendations

- All brain injury patients should be issued with a prescription detailing their neurorehabilitation needs

- A shortfall of 10,000 neurorehabilitation beds should be addressed

- Every trauma centre should have a consultant in rehabilitation medicine

- Neurorehabilitation provision across the UK - and government funding for it - should be reviewed

- Statistics should be collected on the number of patients arriving at A&E with a brain injury, and the number that need and receive neurorehabilitation

The report also states that every three minutes someone is admitted to an emergency department with a head injury. If just one in 100 of these victims end up in prison, this equates to 1,750 people entering the prison system every year.

Before the attack, Schofield was keen on boxing, fishing and hunting in the woods with an air rifle, none of which he is now able to do. Nor can he return to his job as a bricklayer.

But he has learned to drive - his greatest achievement, he says, since leaving Daniel Yorath House. He tires easily of walking, as a result of his injuries, so his car has taken the place of his legs, he says. It also enables him to visit his girlfriend in Essex.

"I've basically achieved everything I want to," he says. "My biggest aim was not to go back to prison."

He has learned to do many things with the use of only one arm, though some remain a challenge - cutting the nails on his right hand is one of, if not the most difficult challenge he faces.

"Day-to-day life is a journey in itself - you've got to learn coping strategies," he says.

Schofield now acts as an ambassador for The Disabilities Trust, returning to Daniel Yorath House to talk to the young men and women who are in exactly the same position he was in not too long ago.

"They helped me, I want to help them," he says. "I think everyone deserves a second chance, don't they? They deserve the opportunity to make better of themselves."

Follow Stephen Menon on twitter at @Stephen_menon

Photos by Alex Cousins/SWNS

You may also be interested in:

Adam and Raquel Gonzales had been together for five years when he woke up one morning with no idea who she was - he had lost all memory of marrying her. But Raquel was determined to win him over again.