The French connection: How Catalonia got its ballot papers

Getty Images

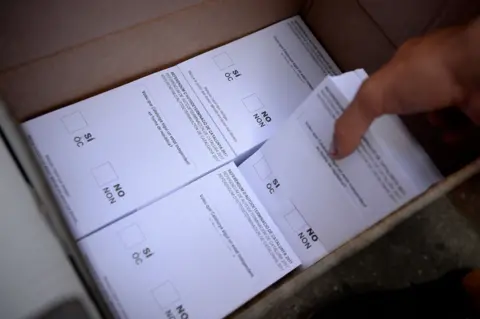

Getty ImagesThis time last year the Catalan government was busily preparing for a vote on independence, even though the parliament had yet to give its final approval. One puzzle was how to obtain ballot papers and ballot boxes - and how to prevent them being seized in advance. The BBC's Niall O'Gallagher visited France to discover how the problem was solved.

Elna is a town not found on any map.

I could tell you that it lies north of the Pyrenees on the road to Perpignan. But if you consulted the chart, you'd find, nestled between the mountains and the sea, only the French town of Elne. Even armed with GPS, I fared no better at first: the address I'd been given returned no results.

Only when I'd translated my destination from Catalan did the disembodied voice of the hire car's computerised navigator splutter into life.

Elna lay at the end of a trail that had begun in Barcelona on 1 October last year. I had waited in the rain for voting to begin in Catalonia's disputed referendum on independence from Spain.

The authorities in Madrid had taken control of the region's finances so the Catalan government couldn't buy ballot boxes or print voting papers. Somehow, despite a heavy police presence, the polls opened as planned. But how?

Contacts in the Catalan capital sent me north to meet Maria - not her real name - striking at 70 with her black hair and fur coat, on a cobbled street above Elna's old walls. We followed her car to a restaurant, which she persuaded to re-open and serve us salad while we talked.

Maria grew up here speaking Catalan at home, and like many others in this part of France feels a deep sense of loyalty to her fellow Catalans in Spain.

So it's not that surprising that in Elna - perhaps over a meal like this, of ripe tomatoes with pungent vinegar - a plot was hatched to evade the attention of the Spanish police and supply those south of the border with what they needed to hold their independence vote.

Find out more

- From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

- Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 BST

- Listen to Niall O'Gallagher's report for From Our Own Correspondent in the wake of the 1 October vote

Maria would introduce us to the plotters.

Her mobile rang and she exchanged a few words in Catalan with the man on the other end of the line. Jaume agreed to meet us later, on condition we would not reveal his identity.

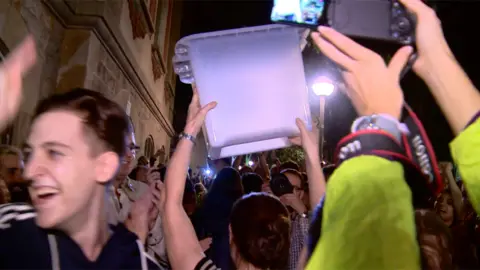

He arrived at our rendezvous carrying a ballot box exactly like the ones I'd seen in Barcelona. Maria made coffee while Jaume, a slight man with a pointed white beard, answered in terse monosyllables my small talk about the children and the weather. Eventually, once my third cup was cold, he began to talk.

"I drove ballot papers from France across the border with Spain in a lorry," he told me. "There was always the danger that some information would be leaked, which would jeopardise the whole operation.

"But I wasn't afraid. All I did was transport paper - and as far as I know, transporting paper from one EU state to another isn't a crime."

The nonchalant humour in Jaume's voice sat uneasily with his desire for anonymity. So far two people I've interviewed while covering this story have ended up in jail.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMaria then introduced us to Jordi, a local activist in his sixties but built like a boxer. He had come to Catalunya del Nord - as the French province of Roussillon is sometimes called - from Terrassa, south of the border, years earlier.

Over peach brandy, a BBC colleague asked whether it was love that had brought him north. "No," he said without smiling. "I was in the resistance during the dictatorship." The ballot-paper smugglers from Elna had traced in reverse the route taken by thousands of refugees fleeing the Franco regime, who came through the mountains in the decades after the Spanish Civil War.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the voting papers were being printed in Elna, the ballot boxes had travelled all the way from a factory in China, via Marseille, before being hidden in the French-Catalan countryside. They were then taken south ahead of the referendum - a day that ended with hundreds injured at the hands of the Spanish police.

"They were held up to ridicule," Jordi told me, "and that humiliation turned to vengeance on 1 October."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter resetting our satnav for our onward journey, I took a call from Maria. She was keen for me to hear one more story before I left.

"Twenty-four hours before the referendum," she told me, "there was a raid on a printing press in the south. Someone called me and said there weren't enough ballot papers left to go ahead. So we found a printer in Elna who opened up in the middle of the night and made more. They were driven across the border just in time."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCatalans are split on independence and no-one knows how this story will end. The Spanish Prime Minister at the time, Mariano Rajoy, has now left the stage. Ousted Catalan president Carles Puigdemont waits in the wings in Belgium.

But when the history of the October referendum is written it might reflect that the machinations of politicians would have come to nothing were it not for a group of pensioners in a tiny French village, who risked their liberty so their fellow Catalans could vote.

They put Elna on the map - but no chart can show the people of this region their destination.

French connection II

Listen to John Laurenson reporting from the Spanish exclave of Llivia, in southern France, on the role it could play in the Catalonian nationalists' next move