Asylum decision-maker: 'It's a lottery'

BBC

BBCThe Home Office has denied taking "arbitrary" decisions on asylum cases in order to meet deportation targets, but an asylum caseworker says staff have to work so fast that the results are a "lottery" - one that could result in people being sent home to their deaths. He contacted the BBC because he wants the public to know how the system operates. As he would lose his job if identified, we have called him "Alex".

Every day Alex reads the case files of people who have fled armed conflict. People who have been persecuted because of their politics, race, religion or sexuality. People who have experienced torture and sexual violence.

It's his job to decide whether these people, all asylum seekers, should be allowed to stay in the UK or be deported.

And yet, when he walks into work, he is greeted by a scene that wouldn't look out of place at a call centre selling double glazing. A leader board hangs on the wall displaying who is hitting their targets and who isn't, and performance managers pace the floor asking for updates on progress as often as once an hour.

Staff who don't meet their targets risk losing their jobs.

"There is an obsession among management with unachievable 'stats' - human beings with complex lives are reduced just to numbers," says Alex who has been a decision-maker for the Home Office for almost a year.

"These are people waiting for a decision to be made on their lives - it is probably one of the biggest things they will ever have to go through.

"Given what we are dealing with, this is not the environment for pushy managers who try to drive results through fear and intimidation."

Alex is one of 140 decision-makers based in an office in Bootle, just outside Liverpool. Most were recruited last year to clear a backlog of 10,000 of asylum cases within 12 months - a project known as Next Generation Casework.

How are decisions made?

- Decision-makers must take into account the evidence submitted by asylum applicants, the political and human rights situation in the country of origin, and previous decisions about asylum taken by UK courts

- Decisions often depend on whether the decision-maker finds the applicant's account to be believable - if it contains inaccurate or inconsistent information, for example, this will be damaging

- The claim may also be harmed if the applicant delayed claiming asylum without good reason, if (s)he did not claim asylum in the first safe country, or has been convicted of a criminal offence such as using false travel documentation

Source: Asylum Aid

The focus is on cases classified by the Home Office as "non-straightforward", including pregnant women, people who claim to have been tortured and those with mental health conditions.

But no matter how complex the case, Alex is expected to make five decisions to grant or refuse asylum seekers a week, justified by a letter that can be anything between 5,000 and 17,000 words long (that is, between two or seven times the length of this article).

Anyone consistently hitting three or less is put on an "improvement plan" - and will be sacked if they don't improve in four weeks, Alex says.

"People will often take decisions based on what the easiest result will be to get through the decision as quickly as possible," says Alex. Sometimes the easiest decision will be to grant asylum, sometimes it will be to refuse it.

"In that sense, asylum seekers face a lottery," he says.

The Home Office told the BBC it didn't recognise the picture painted by Alex and insisted that staff had an "appropriate" workload.

I went to Liverpool to meet Alex and to see his Home Office ID. While there, I also spoke to officials from the Public and Commercial Services Union, who confirmed several aspects of his story.

Who can claim asylum?

Under the 1951 Geneva Convention, asylum seekers must show that:

- They have a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country

- The persecution is for one of the five reasons specified in the Convention: race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion

- They would be at risk of persecution if they were returned

Asked what he means by saying that decision-makers sometimes take the "easiest" route to a decision, rather than the fairest, Alex asks me to imagine that an applicant has given several reasons why he or she needs asylum. In this case, a decision-maker may home in on just one of the reasons, Alex says, rather than considering whether the whole story adds up. In this case the application is likely to be approved, when perhaps it shouldn't be.

But equally, if someone's application contains inconsistencies - regarding dates for example - this can be used as an easy way to refuse an application.

"In reality, some inconsistencies might be down to the person having a mental health problem, or just simply that it has been such a long time between making the claim and having an interview that they've forgotten precise dates of things," says Alex.

There is nothing stopping decision-makers from doing their own research - for example, putting in a call to a UK church where someone claiming asylum on grounds of religious persecution claims to have been worshipping.

"But there are no extra points for going the extra mile - in fact, it only hurts your targets because it takes up time. So people normally just go on the information they've been given," says Alex.

Some of this information comes from two interviews - an initial interview when the asylum seeker first arrives in the country, and a second in-depth interview, conducted by decision-makers like Alex.

These interviews are supposed to last two-and-a-half hours and staff are criticised if they take any longer, says Alex.

BBC

BBC"That target is in people's minds constantly and it's wrong, because how do you fit into two-and-a-half hours someone's story of how they've upped sticks and left the place they were born, the place their family is?"

The pressure to get things done quickly means interviews may be rushed, especially if a decision-maker has two to do on the same day. "We are reluctant to offer breaks, we might be abrupt with asylum seekers, rather than empathetic because we simply need to power through the interview as quickly as possible," Alex says.

Until the beginning of this year, Bootle staff would interview asylum seekers face-to-face at the Capital building in central Liverpool. But now they increasingly do the interviews over Skype.

The asylum seeker will beam in from one location, the interpreter, if needed, from another - and Alex from a small booth in Bootle. It means they've been able to interview asylum seekers living in Leicester, Sheffield, London and Glasgow. But the video link often glitches and cuts out throughout interviews.

The charity Asylum Aid, which gives legal support to asylum seekers, says it has heard of connections being so bad that it's difficult to make out what is being said.

"In a matter of life and death, which is what an asylum interview is, that is unacceptable," says spokesman Ciaran Price.

"Anyone who has ever done a video conference knows it is not as easy to put a point across. The Home Office regularly take into account body language, it will be very difficult to make a judgement about how traumatised someone is when you're relying on a grainy video that keeps freezing."

Alex says it isn't uncommon for people to break down into tears and in that situation, it is good to be in the same room. "I can be sympathetic and encourage them to have a break. I can get them some water and sit quietly with them while they recompose themselves," he says.

Some days it feels too cruel to do otherwise, even if it means forfeiting a target. Alex will often go home after a tough day and break down into tears himself.

Asylum by numbers

- The backlog of people waiting for an asylum decision or for an appeal to be heard is reported to be in the tens of thousands

- More than half of "non-straightforward" applicants had been waiting more than a year for a decision, as of March 2017, according to a report by chief inspector of borders and immigration David Bolt

- 26,350 people applied for asylum in the UK in 2017, according to Gov.uk - a decrease of 14% from 2016

- 14,767 people were granted asylum or alternative forms of protection and resettlement in 2017, including 5,866 children

- Additionally, 5,218 family reunion visas were issued to partners and children of those granted asylum or humanitarian protection in the UK

Sometimes it's not possible for one decision-maker to follow a case all the way through, and in such cases Alex has to rely on notes taken by another interviewer. Reading the case files it becomes clear when the interview has been rushed, as key details will be missing.

For example, it's possible to check whether applicants come from the country they claim to come from by asking the right questions - questions about key landmarks in their town, perhaps, the name of the local public transport network or the country's last-but-one leader. But sometimes interviewers have failed to do this.

"If someone is undocumented, how can you assume their nationality without asking questions?" asks Alex.

"The files are often missing key details and they've forgotten to ask key questions, which makes it very difficult for me to a make a decision."

Again, this can be because the interviewer is rushing. It's rare to have time to read through the applicant's file before going into the interview, Alex says, or to carry out research into the applicant's home country.

When Asylum Aid represented a gay client from Vietnam recently, the Home Office caseworker referred to a Lonely Planet guide to establish whether or not it would be safe for him to return home. Based on the guide's description of Ho Chi Minh city, the caseworker suggested it would be safe for him to go back.

"The target audience for Lonely Planet isn't a Home Office decision-maker. It's a holiday-maker, probably Western, with cash to spend. Unsurprisingly, it doesn't offer holiday-makers the level of detail about the human rights situation that is needed in deciding a person's fate," says spokesman Ciaran Price.

"This is a ridiculous source of objective evidence to use in a decision letter, and is a strong example of Home Office staff relying on information that's quickly available and easy to find - not what is suitable in an individual's case."

BBC

BBCMany of the decision-makers in the Bootle centre are young graduates, with no previous experience of this kind of work and only two weeks of training before they start doing interviews, Alex says.

Everyone else in the office is a temporary worker, employed via a High Street recruitment agency.

This includes the performance managers driving the decision-makers to work faster. "They typically come from sales backgrounds and have never done any work involving asylum seekers or immigration themselves. They have no understanding of the process or how important it is to do things sensitively and properly," Alex says.

He says there are no quotas for the number of applications that must be rejected, the only target is speed - everyone is made acutely aware that the national backlog of cases in progress is in the tens of thousands and that the Home Office is under fire for long delays. But speed affects quality, he says, and the decisions are sometimes overturned on appeal. According to the Law Society, almost 50% of UK immigration and asylum appeals are upheld - evidence of "serious flaws in the way visa and asylum applications are being dealt with".

Asked to comment on Alex's allegations a Home Office spokeswoman said: "We do not recognise these claims made by an anonymous source. We have a dedicated and hardworking team who are committed to providing a high level of service with often complex asylum claims. Their individual workload is appropriate and dependent on their level of experience and seniority."

She added that caseworkers received a proper level of training, and further mentoring if they struggled "to progress cases in line with expected standards". There were also internal audit procedures, she said, to ensure that decision-makers do not simply make what they deem to be the quickest decision.

Across the UK, she said, most interviews with asylum applicants took place face-to-face, though video-interviewing trials would continue.

The spokeswoman said that appeals could be upheld for a number of reasons, including the presentation of new material not available at the time of the initial decision.

Despite the Bootle centre's emphasis on speed, it has failed to clear the backlog as fast as had been hoped.

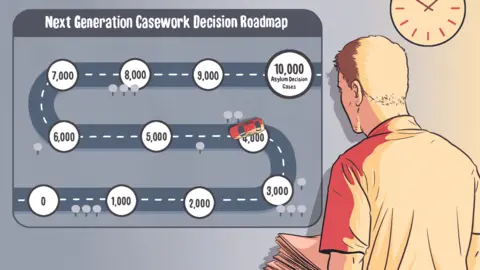

There used to be a big poster on the wall of a winding road with a plastic toy car attached, which was moved to indicate progress towards the 10,000 target. It was taken down some months ago, when it became clear that this would be impossible.

Towards the end of March, coming up to the centre's one-year anniversary, it was announced that 5,000 cases had been completed. (The person who made the 5,000th decision was rewarded with vouchers and some chocolate.)

Problems with staff retention were one factor that prevented the car moving faster. More than a quarter of Home Office staff who take decisions on asylum cases quit over a six-month period, according to a report by David Bolt, the chief inspector of borders and immigration.

Alex is looking for another job, and so are lots of his colleagues.

"I struggle with my job from a moral perspective," he says. "The thing that gets me the most is, if someone is telling the truth but I make the wrong decision and send them back, I'm signing their death warrant."

Illustrations by Tom Humberstone

Follow Kirstie Brewer on Twitter @kirstiejbrewer

You might also like:

They often fled their homelands to escape sexual abuse - but for many asylum seekers, it continues in the UK. Fear of deportation typically means they don't tell police, but one effect of the Harvey Weinstein revelations is that they have now begun to talk about their experiences among themselves.