Pioneering European ERS-2 satellite burns up over Pacific

ESA

ESAA European satellite that pioneered many of the technologies used to monitor the planet and its climate has fallen to Earth.

The two-tonne ERS-2 spacecraft burnt up in the atmosphere over the Pacific.

So far, there have been no eyewitness accounts of the mission's demise or of any debris reaching Earth's surface.

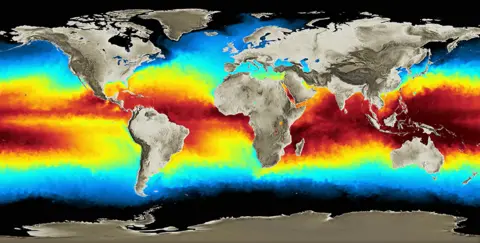

ERS-2 was one of a pair of missions launched by the European Space Agency in the 1990s to study the atmosphere, the land and the oceans in novel ways.

The duo monitored floods, measured continental and ocean-surface temperatures, traced the movement of ice fields, and sensed the ground buckle during earthquakes.

And ERS-2, specifically, introduced a new ability to assess Earth's protective ozone layer.

The satellite's return was expected, although uncontrolled. It had no functioning propulsion system to direct its fiery plunge.

Radars tracked its fall. Esa says the end came at 17:17 GMT (18:17 CET) +/- one minute, over the North Pacific Ocean between Alaska and Hawaii, about 2,000km west of California.

ESA

ESAEsa's Earth Remote Sensing (ERS) spacecraft have been described as the "grandfathers of Earth observation in Europe".

"Absolutely," said Dr Ralph Cordey. "In terms of technology, you can draw a direct line from ERS all the way through to Europe's Copernicus/Sentinel satellites that monitor the planet today. ERS is where it all started," the Airbus Earth observation business development manager told BBC News.

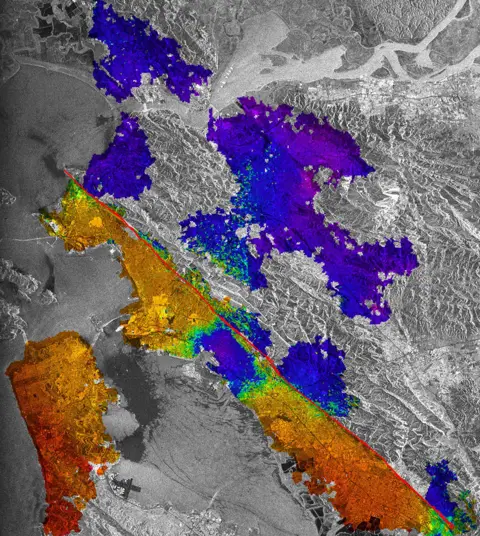

Dr Ruth Mottram is a glaciologist with the Danish Meteorological Institute. She recalled the revolution ERS brought to her discipline.

"When I was a university student in the 90s, we were told that the ice sheets were very cold and stable, and they weren't going to change much; it would take decades before we saw any of the kinds of changes we expected to see as a result of climate change. And ERS really showed that this wasn't true, and that there were big changes happening already."

When ERS-2 ceased operations in 2011, it was commanded to lower its orbit from 780km above the Earth to an altitude of 570km. Controllers then "passivated" the satellite: its tanks were emptied and its battery system fully discharged.

The expectation was that the upper atmosphere would drag the spacecraft down to destruction in about 15 years - a prediction that held true on Wednesday.

ESA

ESAIn the 1990s, space debris mitigation guidelines were much more relaxed. Bringing home a redundant spacecraft within 25 years of end of operations was deemed acceptable.

Esa's new Zero Debris Charter recommends the disposal grace period now not exceed five years. And its future satellites will be launched with the necessary fuel and capability to propulsively de-orbit themselves in short order.

The rationale is obvious: with so many satellites now being launched to orbit, the potential for collisions is increasing. ERS-1 failed suddenly before engineers could lower its altitude. It is still more than 700km above the Earth. At that height it could be 100 years before it naturally falls down.

The American company SpaceX, which operates most of the functional satellites currently in orbit (more than 5,400), recently announced it would be bringing down 100 of them after discovering a fault that "could increase the probability of failure in the future". It wants to remove the spacecraft before any problems make the task more difficult.

Last week, the Secure World Foundation, an advocacy group for the sustainable use of space, and LeoLabs, a US company that tracks space debris, issued a pressing statement on the need to remove redundant orbital hardware.

They said: "The accumulation of massive derelict objects in low Earth orbit continues unabated; 28% of the current long-lived massive derelicts were left in orbit since the turn of the century.

"These clusters of uncontrollable mass pose the greatest debris-generating potential to the thousands of newly deployed satellites that are fuelling the global space economy."