Five climate change solutions under the spotlight at COP28

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's not all doom and gloom at the COP28 climate summit.

The Earth's climate is changing rapidly and urgent action is needed to avoid the most damaging consequences for people and nature.

But there is hope, and delegates in Dubai are discussing several very concrete ways to limit warming.

So what are some of these "solutions", and how are they progressing?

More on the COP28 climate summit

1. Cut fossil fuels

The most important thing is, of course, to cut down on burning fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas). So let's start with that.

They account for more than three quarters of all global greenhouse gas emissions that are responsible for temperatures rising.

As a result, many governments, scientists and campaigners want to see a global agreement on phasing out polluting fossil fuels at COP28.

Encouragingly, global demand for coal, oil and gas are all expected to peak before 2030, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says.

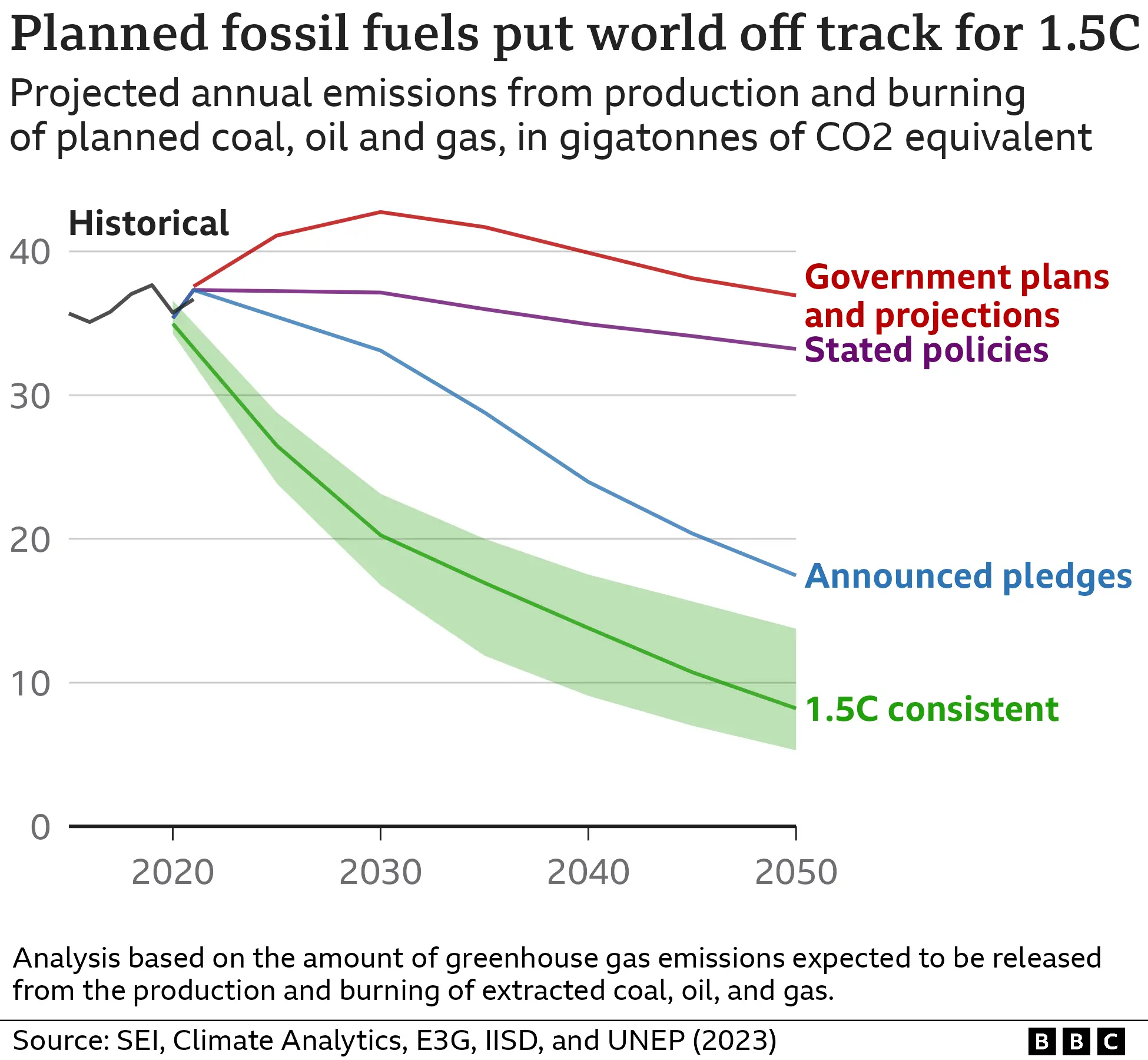

But this is far from enough to meet climate goals agreed by nearly 200 countries in Paris in 2015 - to keep long-term warming "well below" 2C and "pursue efforts" to limit it to 1.5C.

In fact, if all the coal, oil and gas from existing and under-construction fossil fuel projects were fully burned, the world would warm far beyond 1.5C, according to a recent report by the UN's Environment Programme. That's assuming their emissions could not be captured.

But some countries are still increasing production, even though there is no need for investment in new coal, oil and gas to meet the world's energy needs on the IEA's "net zero" pathway.

2. Increase 'renewables'

Fortunately, the world has plenty of alternative sources of clean, renewable energy, like from the wind and Sun.

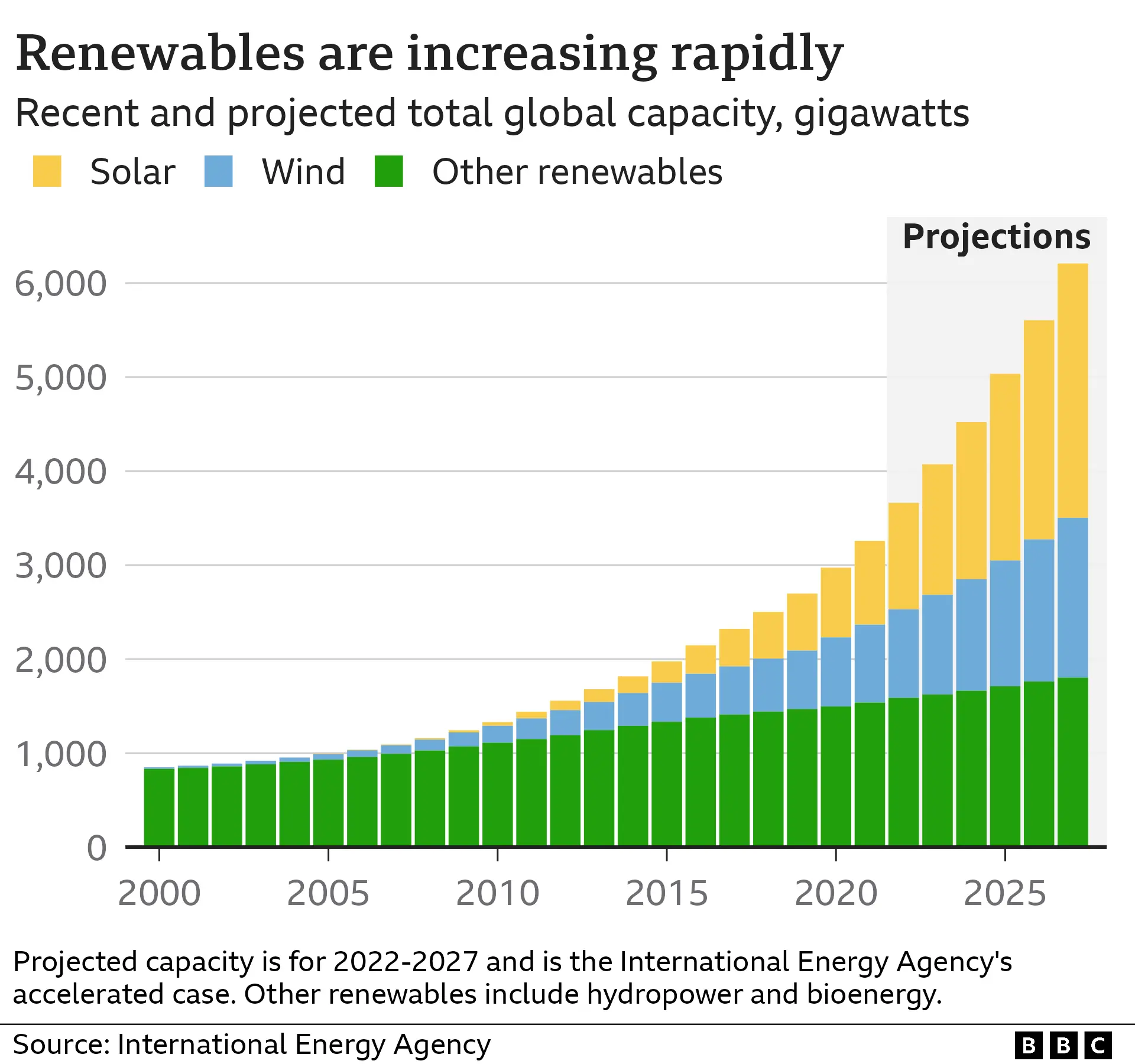

As costs plummet, renewables are booming in many parts of the world - even faster than the IEA expected.

In 2022, solar generation was five times higher than in 2015, while wind generation was two-and-a-half times higher.

By 2030, wind and solar could supply more than a third of all electricity, up from 12% currently, according to the RMI, a US research organisation.

In fact, the switch to solar energy may have already passed an "irreversible tipping point", according to a recent study. This means that solar could become the world's dominant power source by 2050 due to cost and technological trends already set in motion. However, other factors, like the availability of finance for renewables in lower income countries, could be a hindrance.

Other technologies will be needed to fill the gaps when the Sun isn't shining and the wind isn't blowing, like battery storage, nuclear power and "green" hydrogen energy.

But tripling global renewable power capacity by 2030 - which more than 100 countries have promised at COP28 so far - is "vital to keep the 1.5C goal within reach", the IEA says.

3. Switch to electric vehicles

Road transport contributes about 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, mainly through burning petrol and diesel fuel.

Electric vehicles (EVs) have "large potential" to reduce these, according to the UN's climate body, the IPCC.

Over their lifetime, battery EVs cut emissions by around two-thirds on average in Europe and the United States compared with petrol equivalents.

While they don't spew planet-warming fumes, they aren't completely emission-free because fossil fuels are still used to make some of the electricity that powers them.

As this electricity gets cleaner, EVs will have an even bigger emissions advantage over petrol and diesel cars.

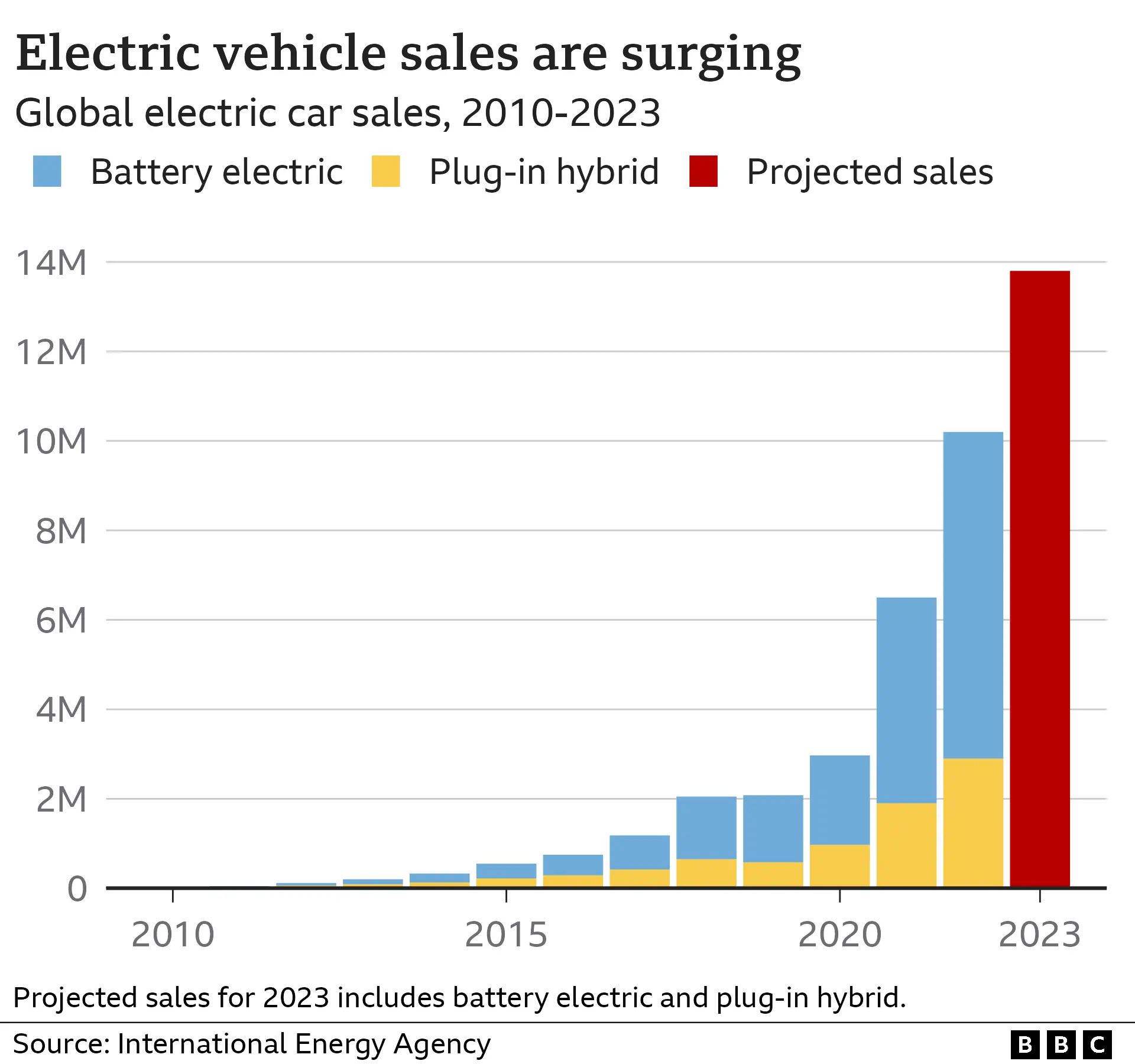

EV sales are surging rapidly. The IEA projects that 18% of new cars sold in 2023 could be electric, up from 4% in 2020. This is dominated by China, the US and Europe, but sales in lower income countries have been slow.

Battery EVs could become cheaper to buy than equivalent petrol and diesel cars within one to three years in some countries, and as soon as 2024 in Europe and China for medium-sized vehicles, according to Exeter University's EEIST project.

This could accelerate the uptake of EVs, so that EVs account for two-thirds of all new car sales globally by 2030, RMI, the US research organisation, suggests.

4. Tackle methane

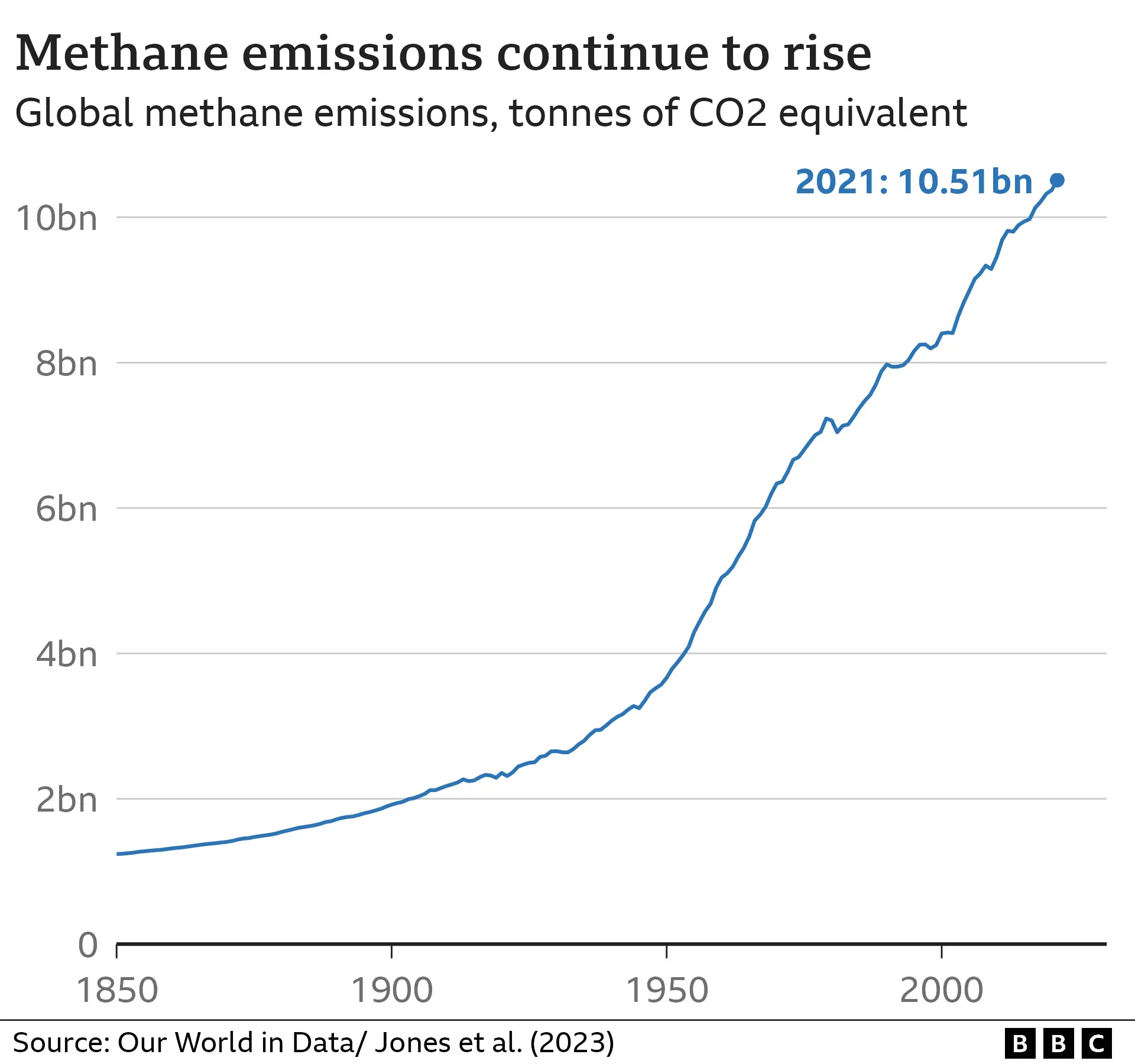

Around 30% of warming is due to methane emissions.

It is much less abundant in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, but pound-for-pound it is about 80 times more powerful as a warming gas over a 20-year period.

However, methane only naturally remains in the atmosphere for around 10 years, compared with centuries for CO2.

So while CO2 emissions are effectively locked in the atmosphere - unless they can be removed by humans - the same is not true for methane.

This means that cutting methane emissions could be one of the most effective ways of slowing warming in the short term.

Key human-caused sources of methane to tackle include agriculture (particularly livestock), fossil fuel production and waste.

Over 150 countries have agreed to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

China, the world's largest methane emitter, has not yet signed up, but has recently released its own plan. It is co-hosting a summit on methane emissions with the US at COP28.

5. Capture carbon

If warming is to be limited to 1.5C, some CO2 will almost certainly have to be captured from source, or taken directly out of the atmosphere.

This is because the world is rapidly running out of time to limit warming to 1.5C. There are also some sectors that cannot yet be easily decarbonised, like agriculture and aviation

CO2 can be captured by natural or artificial processes.

The land and oceans already take up over half of CO2 emissions, limiting the amount of greenhouse gases entering the atmosphere.

EPA

EPABut humans are harming the ability of the natural world to take up carbon, for example through continued deforestation and warming the seas.

Restoring these ecosystems is crucial, but will not be enough on its own. For example, there are limits to the carbon that trees could take up, as well as the area that could be used for tree planting.

Similarly, the industrial capture and storage of CO2 could be important in the future, but is still emerging and remains expensive. These facilities currently capture around 45 million tonnes of CO2 per year, according to the IEA, which is equivalent to about 0.1% of global CO2 emissions.

Crucially, the more humans keep burning fossil fuels, the more carbon will need to be taken out of the atmosphere, even though there is no guarantee this will be possible at the scale required.