'I thought climate change was a hoax. Now I've changed my mind'

Amanda Triplett

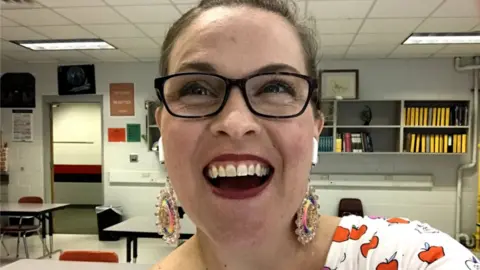

Amanda TriplettSarah Ott spent years believing climate change was a hoax, influenced by friends at church in the US south and a popular right-wing radio host. Here she shares her journey from being a climate sceptic to becoming an advocate for clean energy, with a passion for teaching teenage school students the science of climate change. She features on this year's BBC 100 Women list.

I spent years doubting the science of climate change and spending time with people who didn't believe in the science either.

When I realised I was wrong, I felt really embarrassed.

To move away from those people meant leaving behind an entire community at a time when I didn't have many friends.

I went through a really difficult time. But the truth matters.

I'm the granddaughter of coal miners in Pennsylvania and my family moved to Florida when I was young.

We have a Polish Catholic background and we attended church regularly, but at the same time we were very connected to science because my mum was a nurse and my dad sold microscopes and other scientific equipment.

As a little girl, I loved nature and spent a lot of time outside. For community service, I would always pick up litter in my neighbourhood.

![Sarah Ott Sarah Ott [right] as a child](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/480/cpsprodpb/A63E/production/_131785524_sarahottchildhood.jpg.webp) Sarah Ott

Sarah OttI remember the first time I ever encountered the term "climate change".

I was in middle school in the late 1990s and I read an article about rising temperatures. I remember thinking, "This is really gonna suck". But it also felt like it was so far in the future that it wasn't going to affect me.

I went on to study zoology at university and became a science teacher.

Later my husband and I moved to the state of Georgia, where we still live now with our two daughters.

- BBC 100 Women names 100 inspiring and influential women around the world every year - Sarah Ott is on the 2023 list

- Meet this year's 100 Women here

My husband didn't get home from work until late, so I would have four or five hours at home by myself every day, always with the kitchen radio on, tuned to conservative stations.

We listened to Rush Limbaugh, a radio host known for his controversial opinions on topics such as race, LGBT rights and women, and I would hear him every day for two hours.

He would talk about how climate change was just a hoax.

Up to that point, I had been exposed to a lot of misinformation about evolution in my church groups, but I had studied the theory of evolution at university, so I was equipped to spot it.

But I didn't have that same skill set for climate change.

My conviction that climate change was a hoax solidified when I heard Limbaugh talk about Climategate. It was a controversy involving research from the University of East Anglia. Only much later did I learn that the material was twisted and taken out of context.

When I first heard of Climategate, I remember feeling really betrayed and thinking that scientists had lied to me, because I really cared about the environmental movement.

What was Climategate?

In 2009, hackers stole thousands of emails and documents from the University of East Anglia (UEA)'s Climatic Research Unit in Norwich.

Sceptics picked up on a small number of emails that seemed to suggest scientists had been deliberately manipulating data to exaggerate evidence of climate change.

The material was distributed online and for years it served as fuel for climate-change deniers - including senior US politicians. It was used to support allegations that scientists were twisting the facts.

UEA claimed that the leaked data was cherry-picked and used to derail COP15, the UN climate change conference, which was held that year in Copenhagen.

An independent enquiry cleared the UEA scientists of wrongdoing and concluded that "their rigour and honesty are not in doubt".

I stopped working and stayed home with my two girls while they were babies. I liked it but those were also very difficult years, because I had postpartum depression and anxiety.

I craved intellectual stimulation, so I kept the radio on while I was cooking dinner or while driving in my car. But there were only a few hours of Rush Limbaugh each day.

That's when the big turning point came.

I tuned into NPR, a US non-profit broadcaster. I don't remember which show it was, or the specific news story, but I remember how they described the issue in a completely different way from what I had heard on my usual stations. And it sounded so reasonable.

Suddenly, other news stories I listened to on my usual stations stopped making sense. One that really touched a nerve was about contraceptive pills, which had been framed as something bad, that women just wanted to be promiscuous.

Sarah Ott

Sarah OttI stopped listening to conservative radio shortly after, and I started to consume other media.

I realised how much my social network had changed since I had stopped teaching. At school, I was around people from all over the world, gay or straight, conservative and liberals.

Without that school environment, all I had in my social circle was my church group.

Protestantism in the US south tends to have a strong anti-intellectual background. I really disagreed with their views of the world and what they had to say about gay rights, for example.

But they were my whole life at that time. They were my friends and the people I asked for help when I needed someone to watch my kids.

After the 2016 US presidential elections, when they voted for Donald Trump, I decided that I had to leave that group.

I went back to my job as a teacher and made new friends.

I realised I was no longer a climate denier.

Sarah Ott

Sarah OttThe more I talked to people, the more I realised that many of them shared my feelings - it was such a healing process.

From that point, it's like I've started a new life. I learned about a non-partisan group called Citizens' Climate Lobby, which advocates for climate solutions. I led their North Georgia chapter for a while, and I still volunteer and lobby with them.

I'm also part of the National Center for Science Education, using physical science concepts to teach climate change to my teenage students.

Admitting I was wrong about something quite as big as climate change was really, really hard.

As a descendent of coal miners, I didn't want to slander my family. I'm proud of the work my grandfather did, keeping people's homes warm at that time.

I had to learn to think about it differently and came to the conclusion that I can set an example.

I believe we have to be understanding towards people going through similar journeys and not judge them.

In order to have a conversation with people that still don't believe in climate change, I think we have to connect through the values we share with that person. For religious communities, it may be their desire to protect their children's future. For other people, it may be the belief in having energy independence.

But I always remind myself that there were times when I was so fragile in my beliefs and I was fortunate to have a soft place to land - and other people probably need that too.

How Americans feel about climate change

According to recent Pew Research Center data, the majority (54%) of American adults describe climate change as a major threat. But there is a growing partisan divide: while 78% of people who leans towards the Democrats believe it's a threat, only 23% of those who lean Republican feel the same way.

But there is evidence that people have been changing their minds. In 2018, research from Yale and George Mason Universities found that 8% of Americans had recently changed their opinions about global warming - the great majority of them had become more concerned about it.

Produced by Paula Adamo Idoeta.

BBC 100 Women names 100 inspiring and influential women around the world every year. Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram and Facebook. Join the conversation using #BBC100Women.