James Webb telescope: Icy moon Enceladus spews massive water plume

NASA/JPL/SSI

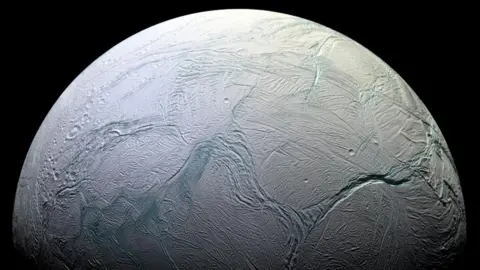

NASA/JPL/SSIAstronomers have detected a huge plume of water vapour spurting out into space from Enceladus, an icy moon of Saturn.

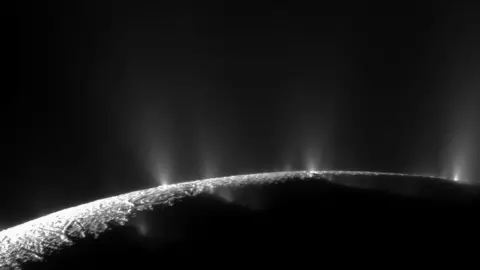

The 504km-wide (313 miles) moon is well known for its geysers, but this is a particularly big one.

The water stream spans some 9,600km - a distance equivalent to that of flying from the UK to Japan.

Scientists are fascinated by Enceladus because its sub-surface salty ocean - the source of the water - could hold the basic conditions to support life.

Nasa's Cassini mission (2004-2017) gathered tantalising evidence of the necessary chemistry by regularly flying through the geysers and sampling the water with its instruments - although it made no direct detection of biology.

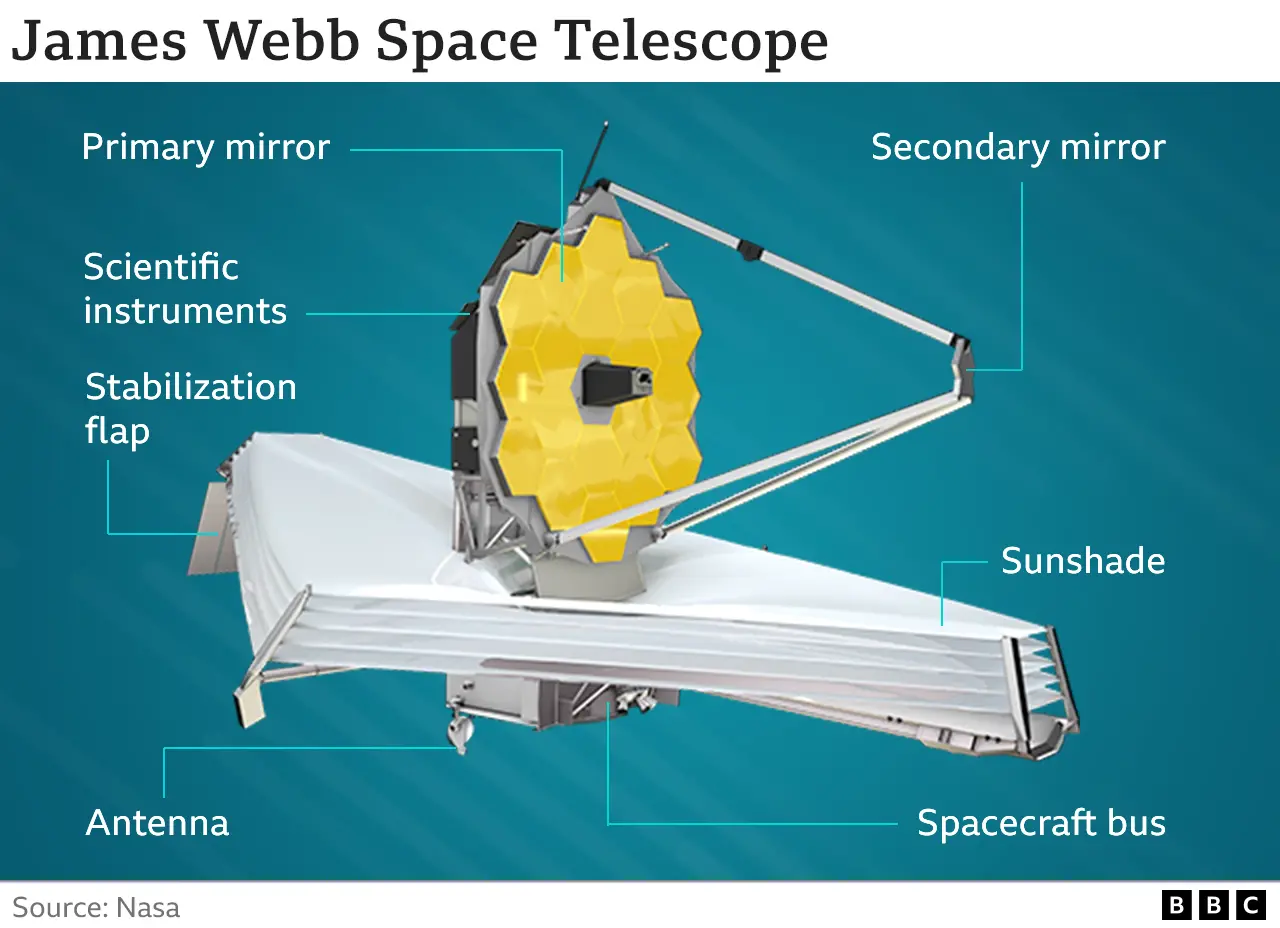

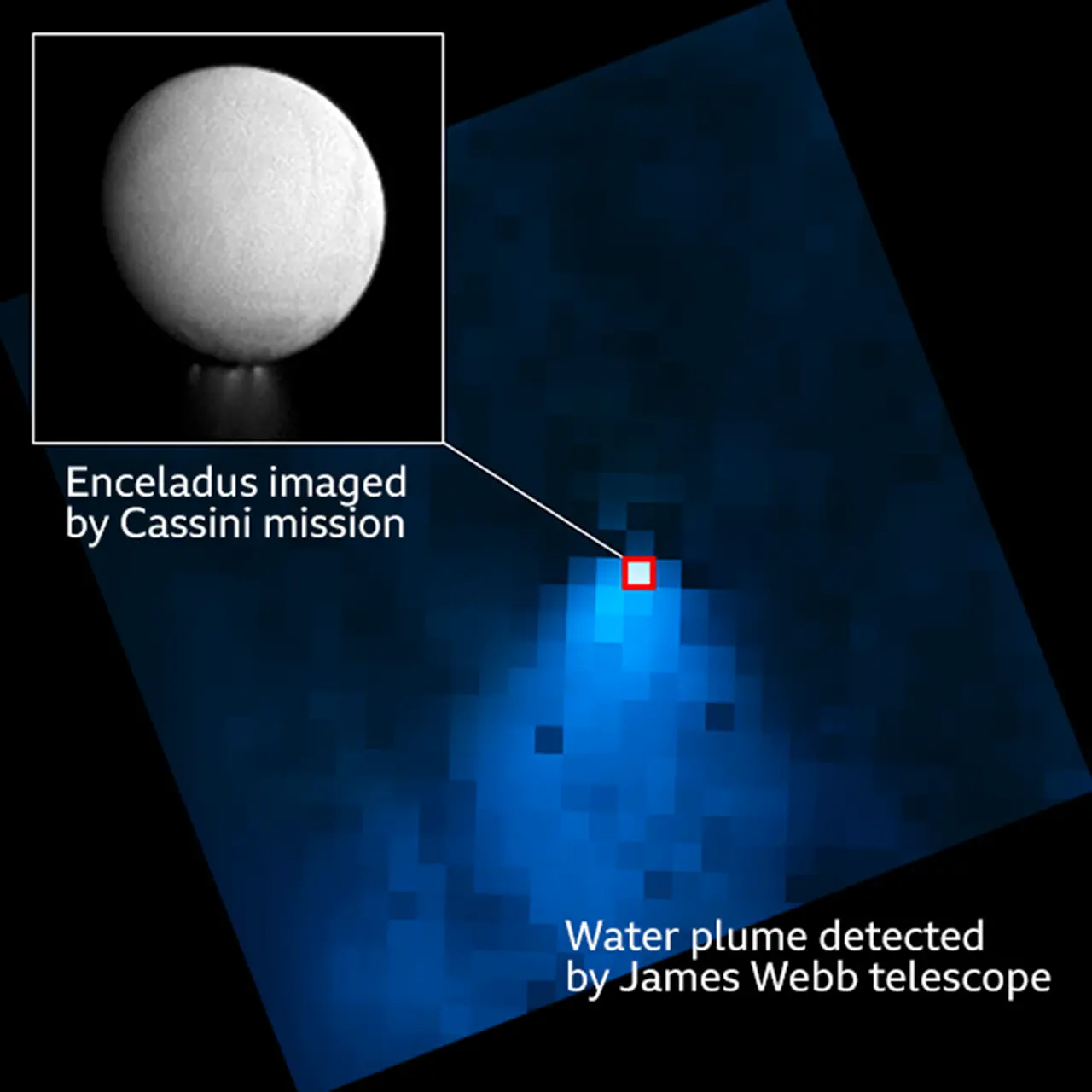

The new super-plume was spied by the James Webb Space Telescope. Previous observations had tracked vapour emissions extending for hundreds of kilometres, but this geyser is on a different scale.

NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI/G.Villanueva et al

NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI/G.Villanueva et alThe European Space Agency (Esa) calculated the rate at which the water was gushing out at about 300 litres per second. This would be sufficient to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in just a few hours, Esa said.

Webb was able to map the plume's properties using its extremely sensitive Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument.

The instrument showed how much of the ejected vapour (about 30%) feeds a fuzzy torus of water co-located with one of Saturn's famous rings - its so-called E-ring.

"The temperature on the surface of Enceladus is minus 200 degrees Celsius. It's freezing cold," commented Prof Catherine Heymans, Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

"But at the core of the moon, we think it's hot enough to heat up this water. And that's what's causing these plumes to come out.

"We know deep in our own ocean on planet Earth, in these sort of conditions, life can survive. So that's why we're excited to see these big plumes at Enceladus. They will help us understand a bit more about what's going on, and how likely it is that life could exist, but it's not going to be life like you and me - it would be deep-sea bacteria," she told the BBC.

NASA/JPL/SSI

NASA/JPL/SSIScientists have proposed a Nasa mission called the Enceladus Orbilander that would try to resolve the open question about life.

As the name suggests, this mission would both orbit the moon to sample the geysers like Cassini did - but with more advanced technology - and then land to sample materials on the surface.

If ever approved, the Orbilander would not fly for several decades because of other priorities.

In the meantime, Nasa and Esa have probes heading to the ice-covered moons of Jupiter. These bodies also contain oceans of water at depth and could actually be better candidates in the search for extra-terrestrial life because they're much larger in size.

It's not known, for example, how long little Enceladus has held water in the all important liquid state to support biology; the moon may have been frozen solid for a substantial portion of the history of the Solar System, denting its life credentials.

In contrast, Jupiter's bulkier moons, such as Europa (3,121km in diameter) and Ganymede (5,268km) have probably had the heat energy to maintain water in the liquid state over a much greater period of time.

A detailed write-up of the Webb observations of Enceladus will appear shortly in the journal Nature Astronomy. A pre-print is available here.