Greenland's future may be written under North Sea

BBC

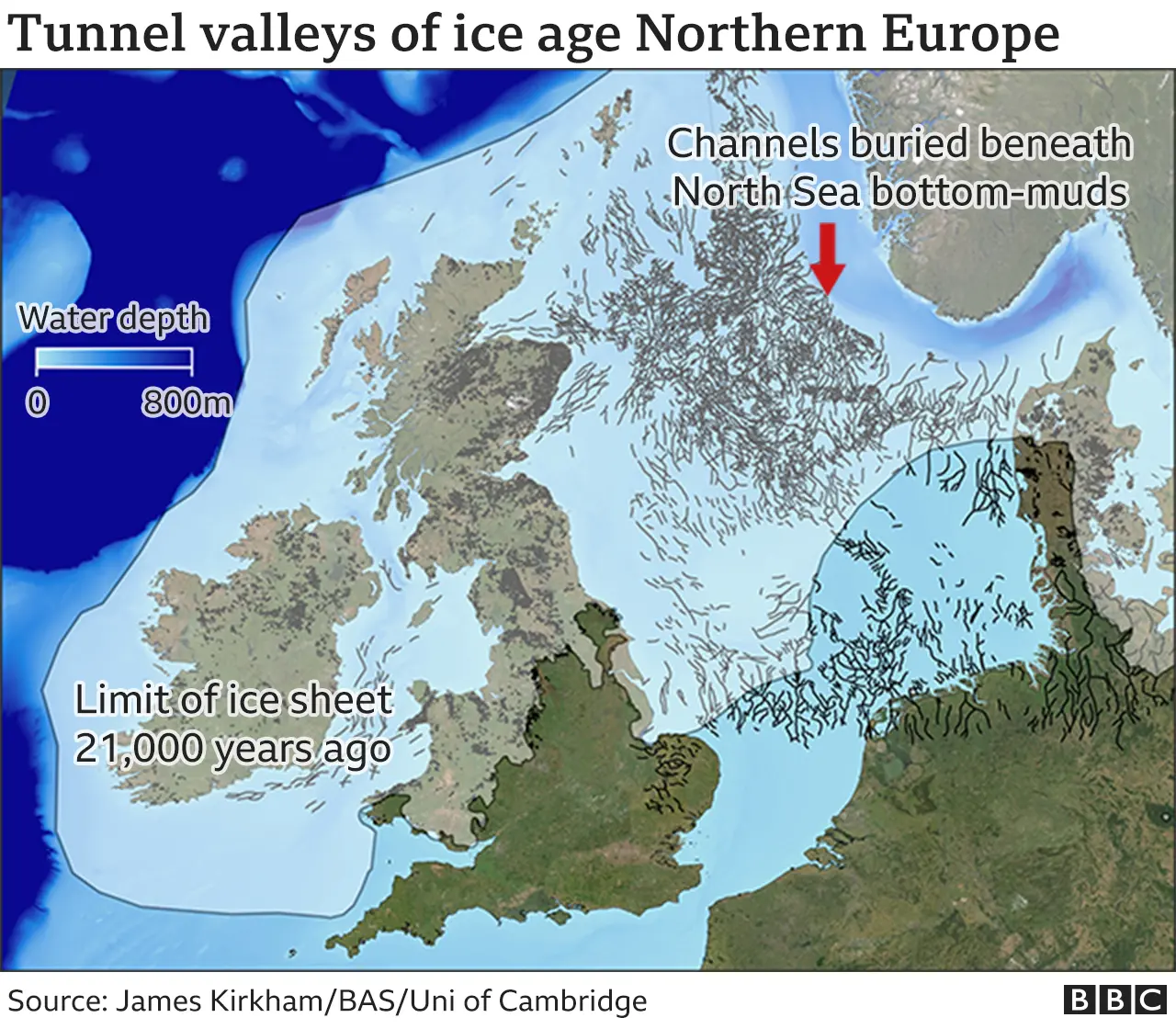

BBCThere are clues to the near-future behaviour of a warming Greenland, and perhaps even a warming Antarctic, buried under the North Sea.

Look below its bottom muds and you will find immense valleys. Hundreds of them.

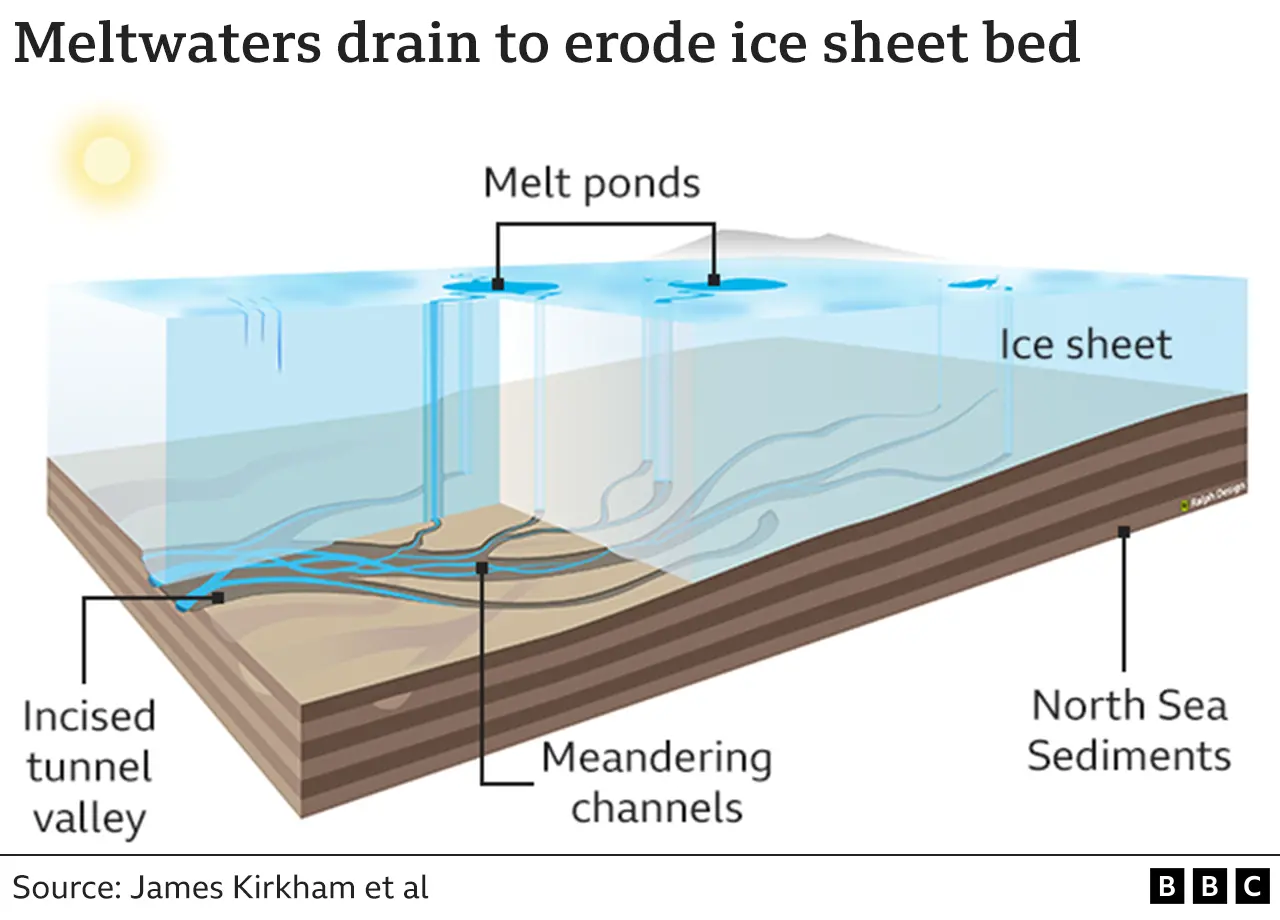

They were carved by rivers of meltwater running beneath the ice sheet that covered Northern Europe towards the end of Earth's last major cold phase.

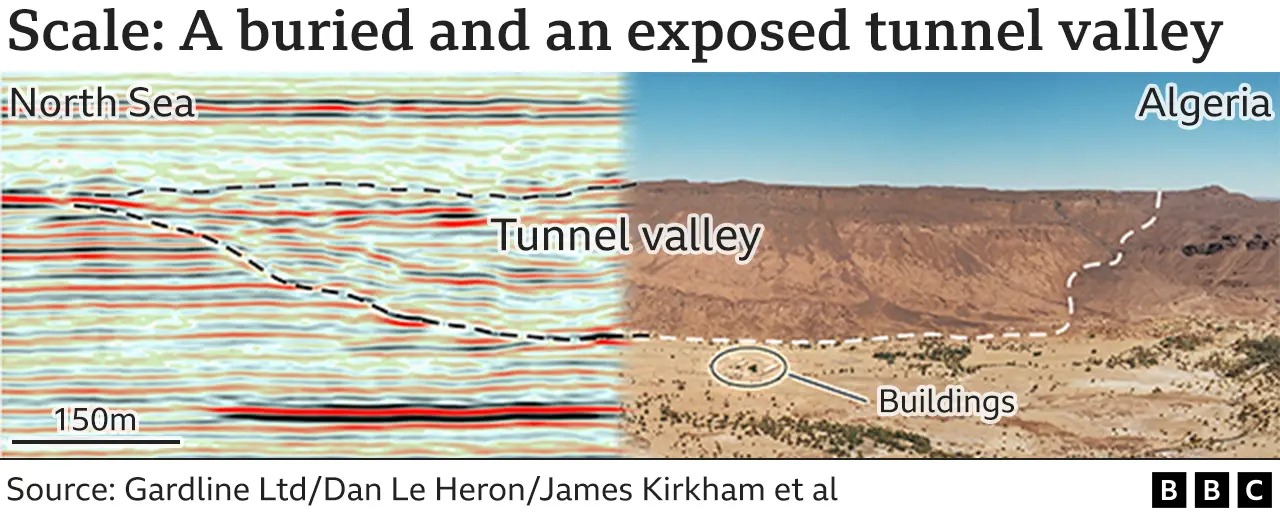

We've known about these valleys (often called "tunnel valleys" because they were incised under the ice sheet) for some time, but only in recent years has their true scale become apparent.

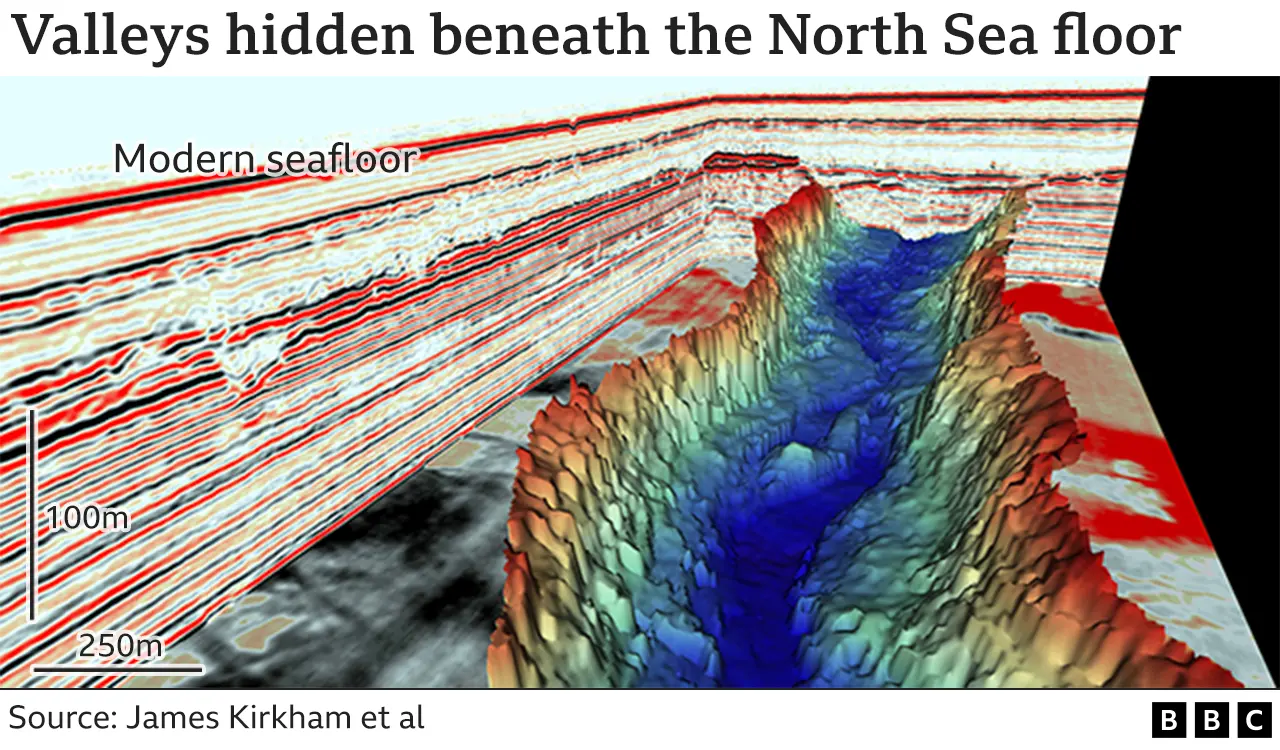

Modern seismic (sound wave) data gathered by oil and gas prospectors has brought a new clarity that has enabled scientists to study the hidden features in greater detail.

In places, the channels are more like canyons - up to 150km long, 6km wide and 500m deep.

I.Joughin/University of Washington

I.Joughin/University of WashingtonThe new advance is in describing the erosional processes involved in cutting the valleys, the speed at which that happened, and the amount of water that could be drained by them.

We're talking discharges of 900 cubic metres per second in the largest channels. To put that in context, English rivers such as the Thames, the Severn and the Trent might only get above 100 cu m/s in flood conditions.

Researchers from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) worked with a team led from the University of Sheffield to decipher the valleys' development as the northern ice sheet advanced and then retreated, between about 27,000 and 19,000 years ago.

The Sheffield team has spent a decade working out the precise extent of the ice in a remarkable project called Britice-Chrono.

The BAS team was able to use this information, along with the high-resolution seismic imagery, to model how the channels evolved.

"We started seeing these smaller channels at the base of the very large tunnel valleys, which seemed to meander and migrate over time," explained BAS PhD student James Kirkham.

"We worked out, basically, that when you force all that water through these smaller channels, they can be extremely erosive. You end up forming the larger channels over just a few hundreds of years. This is really, really rapid on ice sheet timescales."

Streaming large volumes of water under an ice sheet can have implications for its stability. If the water is spread out, it can lubricate the flow, potentially aiding the sheet's collapse - with everything that means for sea-level rise.

On the other hand, if that water can be expelled rapidly in discreet channels, it might allow the ice sheet to sit down more firmly on the rock bed, to steady it.

These are the scenarios now being considered for the future of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

Already, it experiences wide-scale surface melt in Summer.

Water collects in numerous top-side ponds before then draining to the bed and escaping under the ice to the ocean.

If, in the coming decades, similar valleys are cut under Greenland as were incised under Northern Europe's ancient ice sheet, how will that play into the future stability of Greenland?

"There's some debate about whether these rapidly forming channels will accelerate or stabilise ice retreat in a warming world. What we do know, though, is that right now, these processes are not being incorporated at all into our ice sheet models," said BAS geophysicist Dr Kelly Hogan.

"We're looking here at a snapshot of what could happen in Greenland as it gets hotter and hotter. Will the ice go much faster, or slow down? We need to put what we've learnt in the North Sea into the models to see what it does to the ice dynamics."

Circumstances in Antarctica, Earth's biggest ice sheet, are somewhat different to those in Greenland. Certainly, for the short to medium term.

Ice losses in the polar south are driven largely by incursions of warm ocean waters at the ice sheet's margins. Warmer air causing melting and ponding at the surface, like we see in Greenland, is evident in a few places but is less of a factor. This could change, of course, if temperatures continue to rise globally.

Kirkham, Hogan and others have published their investigations of the North Sea's tunnel valleys in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Copernicus Data/Esa/Sentinel-2

Copernicus Data/Esa/Sentinel-2