Apollo Remastered: One man's mission to show us the Moon

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy Saunders

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy Saunders"I've always wanted to see what they saw, to step on board that spacecraft, to look through that same window, and to see what they saw when they walked on the Moon."

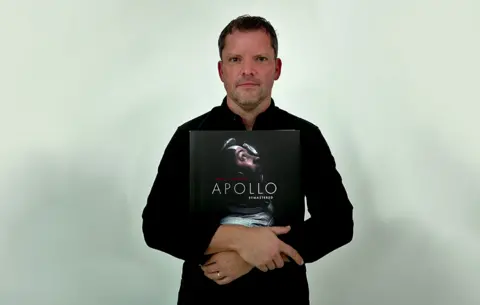

Andy Saunders has an obsession. It's Project Apollo, one of the defining events in our species' history.

But he's also got a deep frustration. And that's the pictures that record those remarkable space missions in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Or, rather, it's the way those pictures are presented to us - often less than sharp, flat, and compressed to death.

It's why the Cheshire property developer took a decision a few years back to put his career on hold and dedicate his time fully to reworking the US space agency's (Nasa) image archive.

The result is a gloriously sumptuous new book called Apollo Remastered. Four hundred pictures that detail humanity's first foray to another world.

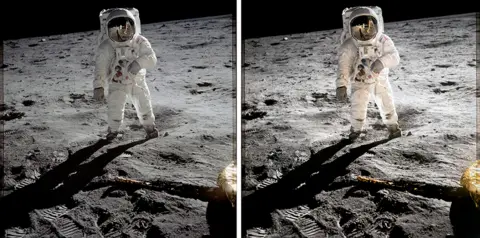

Some of the scenes you'll recognise; they're among the most iconic photos ever taken. But others you will not have seen before; and certainly not in the detail that Andy has rendered them. They have a crispness and depth that makes you want to reach out and touch something.

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy Saunders

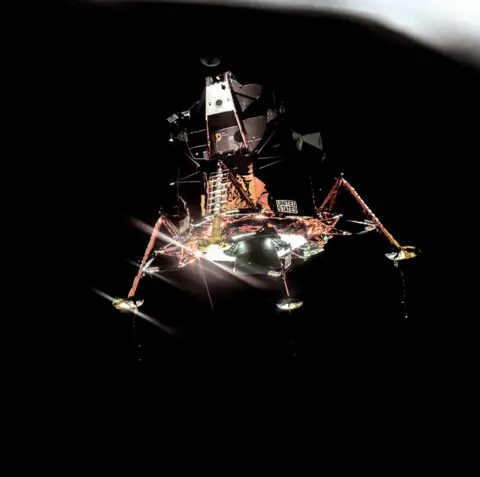

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy SaundersThis success comes, in part, from using very high-definition scans of the original film material (kept in a deep freeze by Nasa to preserve it), but also from his mastery of modern digital editing and enhancement techniques, one or two he's developed himself along the way.

"There's no reason why we shouldn't be seeing these important moments in history in anything other than incredible quality, because they used the best cameras, the best lenses, and the best film that was processed in the most advanced photo lab available. It doesn't make any sense," Andy says.

In his remastered volume, we get to see the only clear, recognisable image of Neil Armstrong's face as he stands on the Moon. (How are there not more pictures of this historic figure on the lunar surface?)

There's the first clear imagery of life on board the stricken Apollo 13 mission, the one that had the near-fatal explosion en route from Earth.

And we get to zoom in on the golf ball Apollo 14's Alan Shepard said he struck for "miles and miles". It barely went 40m.

Some of the most impressive work Andy has done is with the 16mm movie sequences that were captured by the astronauts inside their capsules on the journeys to and from the Moon. There are 10 hours of this material in the Apollo archive. Andy uses a "stacking" technique in his editing software to layer, align and process multiple frames to synthesise one highly detailed image that looks like it's come from a much better quality stills camera.

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy Saunders

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy SaundersA classic example is the view of the "cue card", or "clapperboard", that Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders used in his onboard "home movies". Individually, the frames are blurred and "noisy". But once those frames have been through Andy's computer, we see features that were previously invisible, such as the individual timing hands on Anders' wristwatch.

Andy's favourite remastered image is probably the one that adorns the front cover of his book. Of the 35,000 pictures he reviewed in the Apollo archive, it looked to be among the least promising. It was chronically underexposed.

The only thing it had going for it was a small flash of light towards the top that seemed like it could be a reflection in a window. But in the magic of modern digital software, something truly epic emerged: the Apollo 9 commander Jim McDivitt in his bubble helmet about to manually dock two spacecraft high above the Earth.

NASA/Andy Saunders (Digital source Stephen Slater)

NASA/Andy Saunders (Digital source Stephen Slater)"It's just an absolutely stunning portrait of an Apollo astronaut in 1969, apparently almost looking up in wonder through the window," Andy explains.

"In reality, it's even better than that because McDivitt is actually in the process of undertaking the docking, and the stakes were very high. This was the first time we'd had humans in a spacecraft incapable of getting them home, because they were testing the lunar module and it didn't have a heatshield. So, if they didn't make this docking, they couldn't have come back. It's an incredibly precious moment, an intense moment, a historic moment."

Andy's had to become a student of light and colour. This has involved talking to the astronauts to mine their first-hand impressions. He's also trawled through the hours of mission voice recordings, to pick up any observational details at the time the pictures were taken. He understands the tricks and quirks.

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy Saunders

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy Saunders"There are all kinds of things that affect the colour of the film," he says.

"Some magazines have aged more than others; some were processed slightly differently; some were scanned slightly differently; and if the astronaut took a photograph out of the Command Module window - that's got a slightly different colour tone than if the photo was taken through the Lunar Module window."

In the coming days, Nasa will attempt to recapture the Apollo spirit.

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy Saunders

NASA/JSC/ASU/Andy SaundersIt will initiate its Artemis programme, with a huge new rocket sending a capsule around the Moon. It's an uncrewed test flight that will herald crewed missions later in the decade.

Artemis is sure to be a visual extravaganza. We can expect cameras from all vantage points, 360-degree vistas, 4K definition and live streaming.

Andy says he'll be an enthusiastic spectator, although he doubts all the modern technology will quite match the romance of the old film.

"You know, we're going to see the first woman walk on the Moon, which will be an incredible moment. Hopefully, someone remembers to actually take a photograph."

Apollo Remastered is published by Penguin/Particular Books on 1 September. A collection of photos will also go on tour, starting at London's Royal Albert Hall at the end of September before moving on to the Glasgow Science Centre in November. Andy discusses the photos on Twitter and on Instagram.