Mystery of half-billion year old creature with no anus solved

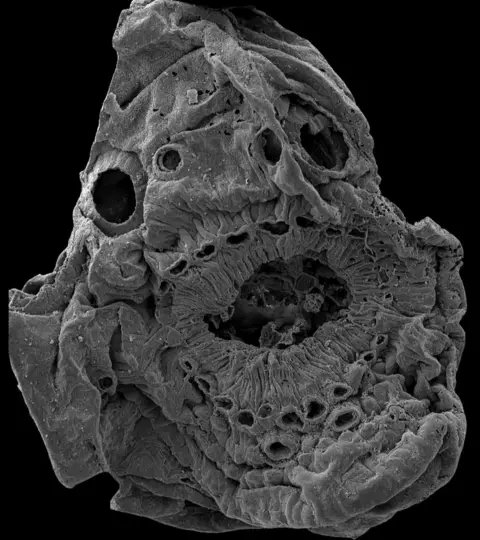

P Donoghue et al/University of Bristol

P Donoghue et al/University of BristolScientists say they have solved an evolutionary mystery involving a 500 million-year-old microscopic, spiny creature with a mouth but no anus.

When it was discovered in 2017, it was reported that the tiny fossil of this sack-like marine beast could be humans' earliest-known ancestor.

The ancient animal, Saccorhytus coronarius, was tentatively placed into a group called the deuterostomes.

This is the group of animals that includes vertebrates.

A new study now suggests Saccorhytus should be put into an entirely different group of animals.

A team of researchers in China and the UK carried out a very detailed X-ray analysis of the creature, and concluded that it belongs to a group called the ecdysozoans - ancestors of spiders and insects.

One source of this evolutionary confusion was the animal's lack of an anus.

Emily Carlisle, a researcher who studied Saccorhytus in detail, explained to BBC Radio 4's Inside Science: "It's a bit confusing - [most] ecdysozoans have an anus, so why didn't this one?"

One "intriguing option", she said, is that an even earlier ancestor of this whole group did not have an anus, and that Saccorhytus evolved after that.

"It could be that it lost it during its own evolution - perhaps it didn't need one because it could just sit in one spot with one opening for everything."

The main reason though, for the "repositioning" of Saccorhytus on the Cambrian tree of life is that, on the initial examination, holes that surrounded its mouth were interpreted as pores for gills - a primitive feature of deuterostomes.

When scientists looked in more detail - using powerful X-rays to examine the 1mm creature closely - they realised that these were actually the base of spines that had snapped off.

Scientists studying these fossils try to place each animals on an evolutionary tree, enabling them to build a picture to understand where they came from and how they evolved.

"Saccorhytus would have lived in the oceans - in the sediment with its spines holding it in place," explained Ms Carlisle, who is based at the University of Bristol.

"It would, we think, have just sat there - in a very strange environment with lots of animals that would have looked like some creatures alive today, but a lot that looked completely alien."

Cambridge University

Cambridge UniversityThe rocks containing these Cambrian fossils are still being studied.

"There's so much we can still learn about its environment," Ms Carlisle added.

"The more I study palaeontology, the more I realise how much is missing. In terms of this creature and the world it lived in, we're really just scratching the surface."

P Donoghue et al/University of Bristol

P Donoghue et al/University of BristolListen to more stories from Inside Science on BBC Sounds

Follow Victoria on Twitter